Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,490

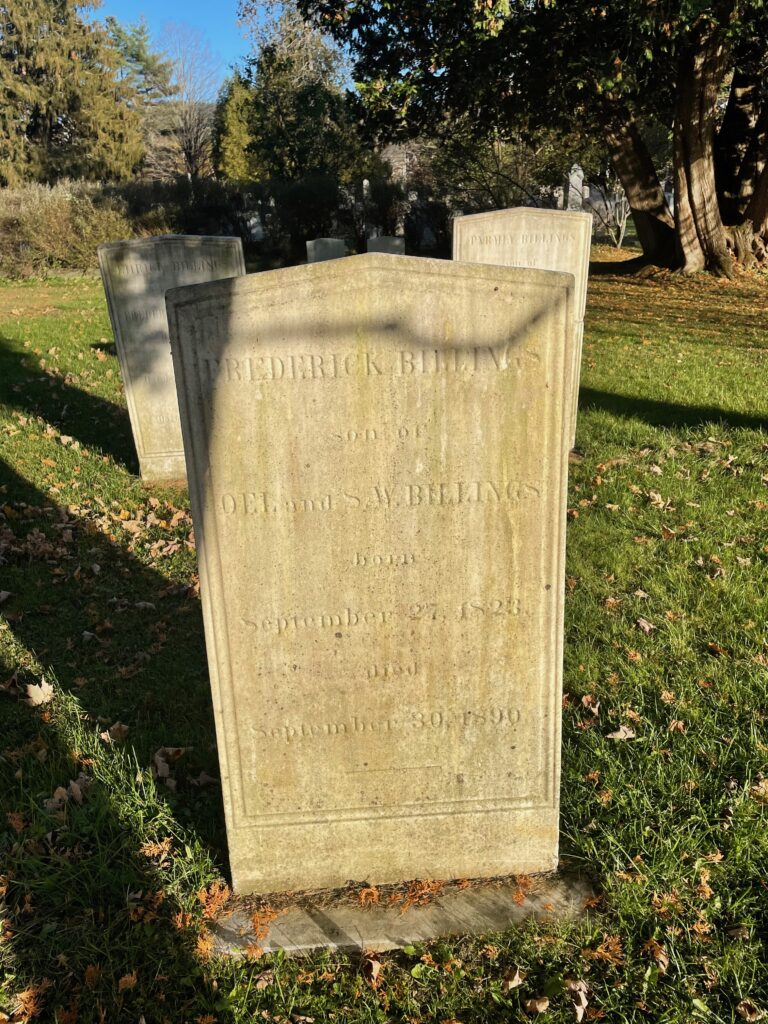

This is the grave of Frederick Billings.

Born in Royalton, Vermont in 1823, Billings grew up in Woodstock. He went to local schools and then to the University of Vermont, graduating in 1844. He was pretty well off and politically connected. A good Whig, he immediately got a job as Secretary of Civil and Military Affairs under Governor Horace Eaton. He was admitted to the bar in 1848. Then, like adventurous young men almost everywhere, he headed out to California for the gold rush. He very quickly realized that the money was not in the gold, but in everything else. He became San Francisco’s first land claims lawyer and there was plenty of work for him in that legally complex and contested environment. Soon he was San Francisco’s commissioner of deeds, chairman of the city’s board of inspectors and judges, and territorial attorney general. Is that all? Among his law partners was Henry Halleck, the future Civil War general who performed so poorly when placed in charge of the Eastern Theater after Abraham Lincoln fired George McClellan for the first time. We can talk about Halleck later in the series and I will have words on the topic. In any case, quite a law firm there.

Billings started amassing a fortune in San Francisco, working in all sorts of fields, but really do well with land deals and reclaiming waterfront properties for development. He was devoted lawyer on land issues and started one of the leading law firms in California with some partners. He even went to Mexico City to do research on Spanish and Mexican land law and claims to help with his cases, at a time when no one did things like this. Part of what he was doing to representing John C. Fremont’s extensive land claims that were squatted on by so many miners that Fremont really had no hope of getting it all back. As per usual, Fremont was a failure. Anyway, no one thought Billings was a failure. Instead, they thought he was a really good freaking lawyer. Pretty quick, this all led Billings to the railroads, which is where he would make his real money. By 1853, he was a millionaire in a world with very few of those. He helped found the University of California in Berkeley and was one of the school’s first trustees, among other charitable and state-building enterprises he spent a lot of time on.

By the time the Civil War came, Billings was a major railroad owner in the West, with his paws all over the California economy. Don’t fool yourself about California. It may have been a “free” state, but secessionist Democrats led by the vile William Gwin controlled the state’s politics and there was as much forced labor, both Black and indigenous, in that state as anywhere else in the country. There was a real chance California could have seceded. Billings led the fight to stay in the Union, and won that, but not by much. Still working with Fremont, he then went to England to try and sell off the explorer’s questionable mining claims and to buy guns for the Union. He did serve as California’s attorney general in 1861 and 1862, but didn’t do much since he was more focused on working with Fremont.

Billings pretty much bailed on California during the war. He met a woman and married her. She wanted to live in New York and so did he. He still had lots of interests in that state, but he could handle them from afar, plus he was so rich that he could hire the best help to look after his interests out there. He ended up leaving New York after the war and moving back to Vermont. He wanted to live in his home, even though he had a big mansion in New York and spent the necessary time there to look after his interests. But with the telegraph and railroad, he could manage this.

As he returned to Vermont, Billings became interested in conservation. He read George Perkins Marsh’s pioneering 1864 book Man and Nature, which demonstrated the ways that Americans had despoiled the environment, focusing on Marsh’s home state of Vermont. This moved Billings greatly. He started buying up properties in Vermont to conserve them and bring back the native forests of the region, at least the best he could. As such, he became one of the nation’s most important 19th century conservationists. Among other things, he was a major player in creating Yellowstone National Park, though as much because his Northern Pacific Railroad hoped to make money of tourism as for a principled reason. He also bought Marsh’s home in Vermont, renovated it for his own mansion, and started his own scientifically managed farm that prioritized both quality livestock, modern forestry, and scenic views for carriage rides. Billings also pushed for scientific forestry within Vermont and spent his time on the issues, serving on the state’s forestry commission.

Billings played at politics, but he wasn’t real successful at it. He was a good Republican, but didn’t have what it took to be elected at tie time. He fought hard for the nomination for governor of Vermont in 1872, but didn’t win the nomination. He tried a couple of other times too for various office, but never was elected to anything. Still, he was an important Vermont insider and of course a connection between the state’s Republican Party and the big money man, of which he was one.

Of course, Billings’ true interest was the railroad. For a railroad capitalist of the Gilded Age, he is considered as at least relatively honest and competent, two skills that were quite rare among the grifting morons and blathering moralistic hypocrites that ended up heading these corporations most of the time. He had purchased 1/12 of the Northern Pacific in 1869, one of the transcontinental projects intended to connect Minnesota to Seattle. Now, the railroads were paid off for building these largely unnecessary and fairly useless lines through land. And oh did Billings like land. He ended up with huge holdings in Montana, which is why the city of Billings in that state is named after him. After Jay Cooke puked up the nation’s economy and specifically the Northern Pacific in 1873, Billings picked up the pieces and saved it from bankruptcy. He became company president in 1879, but lost control in 1881, when Henry Villard managed to take it away and move the Pacific destination from Seattle to Tacoma. But Billings did stay on the board of directors.

Billings had a stroke in 1889 and never recovered. He died in 1890, at the age of 67.

Frederick Billings is buried in River Street Cemetery, Woodstock, Vermont.

Today, you can visit Billings’ home at the Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historic Site in Vermont and get a better sense of Billings’ efforts on conservation. As it turned out, the house and land ended up in the Rockefeller family as his granddaughter married Laurance Rockefeller, himself a major conservationist. They then lived in the mansion and so the park does a good job of discussing rich guy conservation efforts through three figures and three eras, which is certainly an interesting approach that I found worked fairly well.

If you would like this series to visit other railroad executives, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Josiah Perham, first and much forgotten president of the Northern Pacific, is in Cambridge, Massachusetts and George Washington Cass, another NP president, is in Pittsburgh. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.