This Day in Labor History: October 31, 1990

On October 31, 1990, the Ravenswood Aluminum plant in West Virginia locked out its workers, represented by the United Steelworkers of America. Thus began a two year battle that was one of the most intensely fought labor disputes of the late twentieth century. Using a sophisticated corporate campaign against the head of the conglomerate that owned Ravenswood, the vulture capitalist and criminal Marc Rich, the USW got a huge amount of attention, generated a significant amount of public pressure, and eventually won.

Ravenswood Aluminum had started as part of the Kaiser Steel empire that became one of the nation’s most dominant companies during World War II. Kaiser opened the plant in 1954. This company was known for its good relations with unions, its pioneering health coverage plans, and other realistic moves it made to recognize that this was the second half of the twentieth century and corporate America needed to act like adults. So between its opening and 1988, there was never a strike, even though the Steelworkers represented the workers. Collective bargaining was the name of the game.

But the 1980s brought rapid changes to American capital. Globalization, cheap imports, new forms of capitalism that rewarded short-term gain over long-term vision, and a concerted corporate effort to roll back the last half-century of labor wins changed the game. For Kaiser, it meant selling off all of its aluminum plants. This was your classic leveraged buyout, with the new company just wanting to slash costs and increase profits. The new CEO (not that he was really running the show at the international corporate level) despised the union. He had worked at the plant before and this was very personal for him. He wanted to crush the union.

The new owners had absolutely no interest in continuing those smooth relations. It wanted to bust the union and it did everything possible to make that happen. Beforehand, it started making crazy purchases–tear gas, bullet proof vests, things that showed it was prepared for literally anything. The first step in union busting process–and one that was tremendously common in the 1980s such as with Phelps Dodge in Arizona–is to offer a contract so insulting that it forces the workers to strike or create a scenario where you can lockout the workers. Then you hire all the replacement workers you can. That is what the new employer did. Even before this, it prepared the way by cutting corners of safety. In the summer of 1990, four workers died on the job. That is a lot of workplace death for this era! The workers were furious. So when they made contract demands, a lot of them were about workplace safety. The employer didn’t care and wouldn’t budge. So it finally just locked the workers out on October 31, 1990. About 1700 workers all of a sudden stopped getting paid.

This got very ugly very quickly. For the next 20 months, the town of Ravenswood effectively lived in a civil war. That included shootings, though no one died. But there were people being beaten up, property destruction, intimidation. The old days of labor violence seemed to be returning to West Virginia. Now, this was all because the company were a bunch of bastards. In fact, it is illegal to hire replacement workers during a lockout. It openly broke the law and then put tons of pressure on the bought and sold corporate hacks who run West Virginia to rule that this was not in fact a lockout. The state’s Department of Employment Security was happy to comply. USW Local 5668 had a strong sense of solidarity. And it had a good legal strategy–appeal to the National Labor Relations Board. After all, this was obviously illegal and the company really had contempt for both the union and the NLRB.

What made a huge difference was the corporate campaign. This was a very big thing starting in the 1980s. With the conglomeration of capital, these employers were connected to multinational corporations involved in economic activity across the world. And since this was the Greed Is Good era, a lot of these people were open criminals (this hasn’t really changed, just today they are hoodie wearing techbros instead of slick NYC scumbags like Gordon Gekko), and one of them involved in this company was the infamous Marc Rich, noted tax evader, trader of oil with Iran during the hostage crisis, and later a good buddy of Bill Clinton, who pardoned him. So Rich gave the union a real big target. When Rich and other leaders of the conglomerate met in nations such as Switzerland and the Netherlands, international brigades would show up and do a real loud protest. This was real solidarity between American unions and European unions. Another big difference came from the development of a women’s brigade. This was still a pretty male workplace but the women stepped in to prevent company thugs from committing open violence, raising spirits, raising money, and doing other support work in the classic form of the union auxiliaries of the mid-20th century.

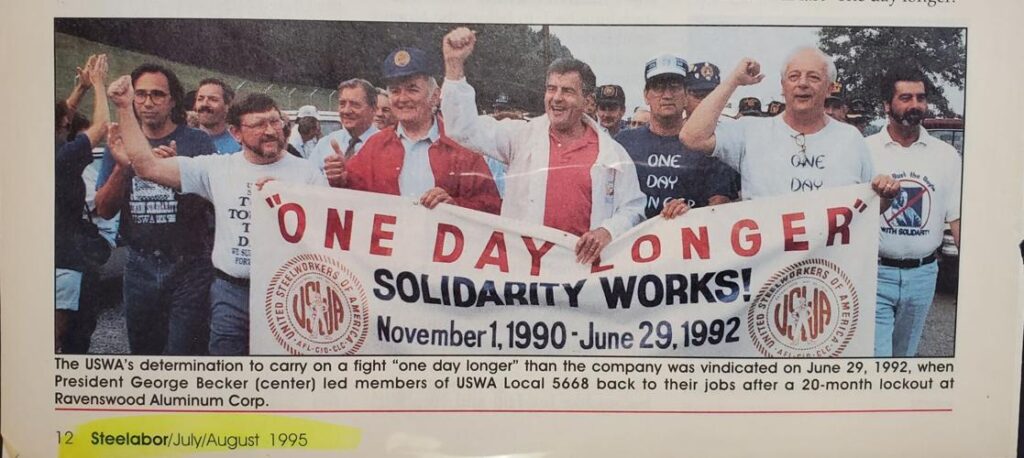

Finally, the employer caved. The National Labor Relations Board was going to come down hard on the company and so it finally worked out a deal with the USW in June 1992. The corporate campaign was critical here, not because it really impacted the finances per se, but because the bad publicity kept this obscure plant in a small West Virginia town in the headlines and that was bad for the company.

In a time when labor was losing left and right, this was a serious victory. It didn’t portend any big changes in the trajectory of the labor movement, unfortunately. But even a defensive win like this was a critically important victory that demonstrated that solidarity could still matter in America.

In the aftermath, the company sold the plant in 1995 and then it closed in 2009. However, a new plant opened on the site in 2021 that employs about 1,100 workers, which is a lot and is generating a lot of money in a poor part of West Virginia and Ohio (the plant is on the Ohio River).

I borrowed from Tom Juravich and Kate Bronfenbrenner, Ravenswood: The Steelworkers’ Victory and the Revival of American Labor to write this post. To say the least, Ravenswood did not lead to the revival of American labor, but then labor scholars always love to exaggerate how this current moment is the one that will finally bring the labor movement back. Me, I’d suggest a bit more skepticism about such claims.

This is the 502nd post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.