This Day in Labor History: October 30, 1962

On October 30, 1962, 13 members of United Steelworkers of America Local 2401, working with Herbert Hill, one of the top officials in the NAACP, filed a decertification petition over the continued segregation and racism in their local. This moment of civil rights activism both within and against the labor movement is a moment where we can explore the difficulties unions had in overcoming their internal racism.

The creation of the CIO in the late 1930s had the promise of bringing American workers together regardless of race to fight for equality on the job. One of the reasons the CIO was necessary is that the American Federation of Labor simply would not organize the industrial spaces where many Black workers had their jobs. Those same spaces also often included many white and immigrant workers too. And the CIO did have very real moments of interracial unionism and racial equality, most notably in the United Packinghouse Workers that organized meat packing. But more often, it was a lot easier to talk about racial equality than enforce it on the job. It never did take long for immigrants from Europe to realize that anti-Black racism was a ticket to whiteness. Moreover, there were plenty of Black workers in the steel or auto plants by World War II, but job classifications often remained pretty segregated. Moreover, whenever union leaders did try to press on racial equality, such as the United Auto Workers’ Walter Reuther, local workers would push back very hard and even vote for Republicans who hated their unions.

So none of this was easy. The rise of the civil rights movement put more pressure on unions to act. But could they act without alienating their white members? Did the leaders even want to act? It really depended on the union. The USWA had attempted a broader desegregation in 1950 but widespread grassroots resistance resulted and it backed off. And when USWA head Phil Murray came to Birmingham to speak to his workers, Bull Connor, already terrorizing the Black community, put a rope up in the middle of the room to enforce segregation, something the white workers wanted. Sigh. Murray did not challenge it. David McDonald, who replaced Murray in 1952, was even weaker on civil rights. He didn’t care much and certainly wasn’t going to burn capital on the issue. He was happy to work in Washington to give labor support for legislation, but within the union? Forget about it. Black workers in Birmingham frequently wrote to McDonald about the discrimination they faced within the union but he was reluctant to even respond.

Meanwhile, by the late 50s, Black workers started working with civil rights organizations to challenge the aging and often racist, if once politically radical, union leaders around the nation. There were big challenges to the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, where Clara Lemlich and other leftist Jewish women had once challenged capitalism, but whose current leadership saw their growing Black membership with suspicion. People such as Adam Clayton Powell and NAACP leader Roy Wilkins took on their case.

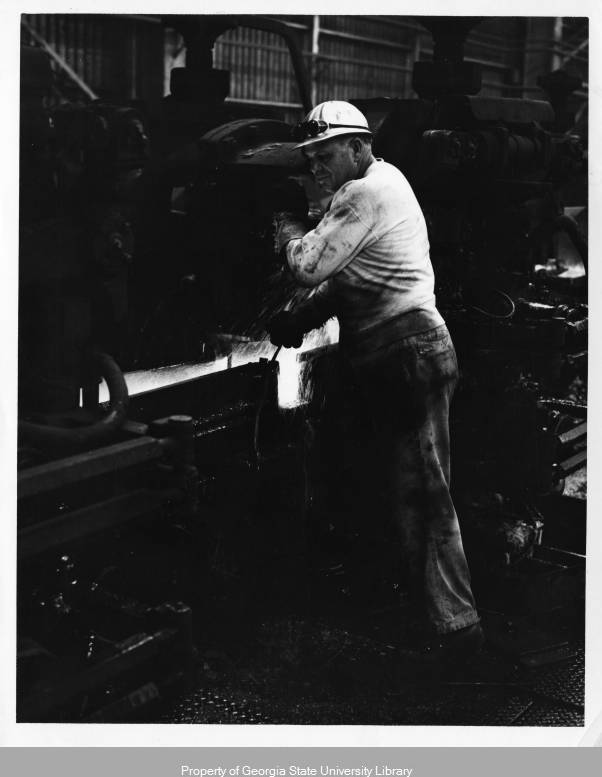

In the USWA, this came to a crisis point with the Atlantic Steel plant in Atlanta. There, in one of the hotbeds of the civil rights movement. The company had good relationships with Local 2401 generally, but some of that is that both sides were happy to maintain the racial status quo. Black workers, activated by the lynching of Emmett Till, began to organize among themselves. They made connections with Herbert Hill, Labor Secretary of the NAACP. This began in 1957. Black workers maxed out pay at about half of what whites did and the union would do nothing about it. Blacks were hired only as “common laborers” whatever they did, which was the lowest paid job classification.

Hill started a real investigation here. His findings led the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights to investigate as well. Given that Georgia was a right to work state, the workers had a card to play–quitting the union. That’s not what they wanted, but it was a tool. Hill actually had to convince the workers not to quit the union and he agreed to represent them to both the company and the union. But the union just completely botched all of this. It was concerned, but it just didn’t pay enough attention to what the Black workers wanted because it was too concerned about the white workers. There were some offers to work toward small changes in the contract that would provide incremental assistance, but that is very much not what these workers wanted. Language in a contract negotiated in 1961 and another in 1962 infuriated that core of workers.

So, after the 1962 contract, 13 Black workers of Local 2401 got the NAACP to file a petition of decertification with the National Labor Relations Board. The USWA was highly dismayed and argued that it had made progress with the company. This wasn’t false, but it was far short of equality on the job. The union created a full press of older Black workers around the country talking about how much the union had helped them, but for young workers, these were old men and it made no difference in their lives. They were impatient young activists involved with civil rights both on and off the job. They weren’t going to accept second class citizenship any longer.

In the aftermath of this (and I am pretty but not 100% sure that the union was not decertified) the USWA did work harder. It put up a bunch of money to bail out civil rights protestors in Birmingham during the 1963 struggle. But they just couldn’t move properly at all. It did not endorse the March on Washington like the United Auto Workers had. It was more concerned with disorder from Black workers in the union than it was with achieving equality. The union ended up more interested in expanding job training program for Black workers and their sons (not their daughters of course). And there was nothing wrong with this of course. But white union leaders just could not get out of their way in this era to listen to Black workers the way they needed to and while this is not why the unions declined in the U.S., it certainly didn’t help.

I borrowed from Bruce Nelson, Divided We Stand: American Workers and the Struggle for Black Equality to write this post.

This is the 501st post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.