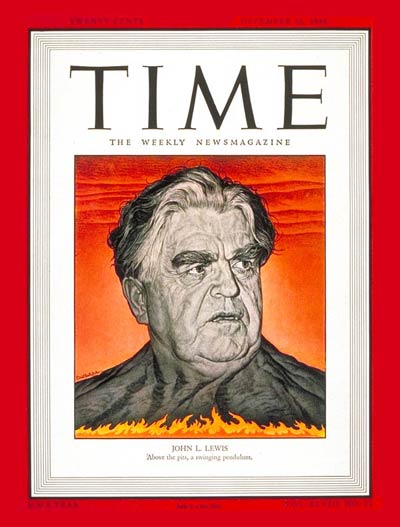

This Day in Labor History: October 25, 1940

On October 25, 1940, John L. Lewis gave a speech denouncing Franklin Delano Roosevelt and endorsing the Republican presidential candidate Wendell Willkie. This alienated Lewis from the rest of the CIO, which he had founded and funded. To his credit I suppose, he resigned as head of the federation and then pulled his United Mine Workers of America out of the federation.

Lewis transformed the labor movement when he decided to leave the American Federation of Labor in 1937. Creating the Congress of Industrial Organizations and then marching out of the AFL brought millions of people into the labor movement. The AFL simply was never going to organize on an industrial basis until they were absolutely forced to do so and that’s what Lewis did. Lewis employed boatloads of communist organizers to organize workers ranging from auto factories in Detroit to the mines and fields and timber camps of the American West.

But don’t fool yourself–Lewis was a politically conservative man. He wasn’t an idiot–he understood what was needed for the labor movement to survive. But Lewis, like most of the old AFL leadership, was fundamentally a man with 19th century values. These were people who did not actually like class conflict that much. They did not like the U.S. engaging in the world. Many of them–though most certainly not Lewis–still thought categories of workers that mattered in the late 19th century were all that were important in the 1930s. One of the things that made Lewis infamous is him punching Carpenters president Big Bill Hutcheson on the floor of the 1935 AFL convention over the issue of industrial unionism. But those guys were old poker buddies and they were both Republicans their entire lives. Lewis would use the communists to serve his interests, but he was no radical at all.

So when the CIO formed, most of its leaders quickly realized that its future was going to be tied to the Democratic Party. Once huge difference between the federations was their understanding of politics. The AFL preferred to stay above politics. Their leaders were naive. They still thought the future of labor was a contest to be decided between unions and employers in the contract, without a role for the government. The long history of government putting its thumb on the scale for the employers did not seem to break this. But new CIO leaders such as Sidney Hillman worked hard to seal those connections. They knew that the Roosevelt administration had created the legal conditions for unions to succeed, through the National Labor Relations Act and the Fair Labor Standards Act, not to mention the Supreme Court appointees.

But none of this made Lewis comfortable. He still saw the future of labor as between his workers–who he was happy to mobilize to flex their power–and the employers. Moreover, like a lot of the AFL labor leaders, he was fundamentally an isolationist. He was very uncomfortable with FDR’s increased involvement in Europe.

So Lewis came out against FDR and went so far as to endorse Wendell Willkie for president. Now, Lewis’ move wasn’t strictly cynical. He seems to have really believed that FDR should have been a bought and sold man of the labor movement. He felt that Roosevelt did not put enough effort behind getting labor legislation passed. He felt that organized labor needed political independence to play the parties off each other and increase their power. He was concerned that organized labor would just become a junior party in the Democratic coalition that didn’t have real power but also didn’t have the ability to extricate itself. He wasn’t wrong about this. That’s exactly what happened to organized labor in the postwar period and it continues to be a problem for the labor movement today, though less under the Biden administration than it has for a very long time.

When Lewis denounced FDR, he quickly found out that the rest of the CIO didn’t see him as the leader he thought he was. He had some suspicions that would happen. Lewis was also an autocrat’s autocrat, a man with a long history purging his union of anyone who challenged his power. But other labor leaders were less likely to put up with this from him. They might be autocrats too–many of them were–but they weren’t going to put up with it from Lewis. So Lewis pulled the UMWA out of the CIO in 1942. This was a serious move. He had mostly paid for it after all. And his lieutenant Phil Murray, who now headed the Steel Workers Organizing Committee, did not follow him out. Murray understood what made his union succeed and it wasn’t Lewis’ feelings. It was the government sitting the steel companies down and telling them as the war started that if it wanted contracts from the government, it was going to have to accept the union.

Lewis did not just then sit on his hands. He simply was not going to sit back and let the government dictate the terms of employment to labor during the war. Almost every union gave a no-strike pledge, but not the United Mine Workers. Lewis was more than happy to pull his workers out of the mines during the war, imperiling the war effort. In 1943, he did this very thing and 500,000 people went on strike. For Lewis, the war effort simply was not worth considering for a labor leader. He was there for his workers and if the employers didn’t like it, they should give the miners what they wanted. The government saw this situation somewhat differently, to say the least. Roosevelt nationalized the mines and Congress passed the Smith-Connally Act in 1943, which laid the groundwork for the Taft-Hartley Act that busted much of labor’s successful tactics in 1947. Alarmed, FDR vetoed Smith-Connally, but Congress overrode the veto, demonstrating just how much Lewis had overplayed his hand.

This is the 499th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.