This Day in Labor History: October 18, 1861

On October 18, 1861, the Phulaguri Uprising began in Assam, modern-day India. This was a revolt against the British control over Indian workers in the aftermath of the 1857 Indian Rebellion. The intense new farm and income tax policies enacted by the empire were a tightening of colonialism and the Indians were not willing to stand for it without a fight. The British were of course more than happy to kill a bunch of Indians in return and this would be disastrous for the people who rose up.

Indians had lived under forms of colonialism for a long time by the mid 19th century, going back to initial attempts by the Dutch and Portuguese to expand their interests into the subcontinent in the 16th century. The British arrived a little later but by the 18th century, were the dominant colonial force there. But this early colonialism was a bit more distant. The Europeans had less interest and capacity to rule on a day to day basis. It was easier and still quite profitable to use proxies to get the goods.

But by the mid 19th century, British colonialism had tightened considerably. By this point, the British were a global empire and the most powerful nation in the world and they meant to profit off it. Especially in incredibly profitable India, the British had no intention of leaving profit on the ground. They intensified their rule, moved toward direct conquest, and then taxed the living hell out of the inhabitants, all while trying to drive them into a coercive globalized economy as low level production workers for things the British would turn into money. In 1857, this led to a rebellion that was more of a civil war. Some Indians were fine with British rule, others were horrified and outraged. The rise in taxes and forced labor were key parts to this rebellion. The death toll was unbelievable. About 6,000 British died, but about 800,000 Indians died, many due to a famine that hit that year and which the British did nothing to help. Famine in fact would become a long time ally of British rule and they routinely did nothing about it, including demanding that exports of grain to Britain continue, even as the Indians literally starved to death. Have to serve the iron law of the market after all.

Well, the British took no mercy after uprisings too. As with the aftermath of the Opium Wars with China, the British were exceedingly punitive in punishing rebellious brown people who did not subject themselves to the British obsession with “free markets,” by which they meant rank exploitation. So they made India pay for the 1857 uprising. Moreover, one upshot of the rebellion was that control over India moved from the East India Company to the crown. So the state needed to pay off the stockholders and it was going to be India who paid for that too. That just meant more taxes, more control, more oppression. So workers raising crops, cutting timber, harvesting fish, and taking care of silkworms all faced new taxes. Then it was expanded to the opium growers. Given that the British had directly incentivized opium crops in order to force feed the Chinese market, this was extra shocking for those farmers. Then, after all that, it expanded the taxes to the betel left and areca nut farmers. Basically, if you worked in India, you now owed the British government most of your money. This was true regardless of what you had done in the 1857 uprising. The British most definitely did not care.

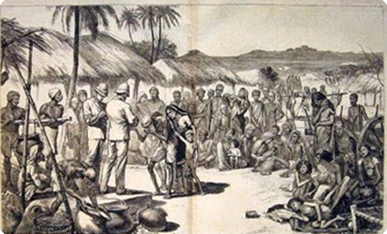

The new uprising began in Nagaon, in Assam, which is the far east of India, near modern-day Bangladesh. That town had a lieutenant named Herbert Sconce. Now, anyone who had read Orwell probably has a pretty good sense about this guy. His contempt for the “natives” was intense. He was there to pull out resources and by god that is what he was going to do. So when a group of farmers tried to meet with him to discuss the taxes, he refused. They then broke into his office and he had them arrested. This just escalated the situation. On October 9, there was a larger protest outside his office. He refused to meet with them and sent a message that there were no plans to tax the betel. This was a lie of course. They did not believe him anyway. On October 15, Sconce sent police to arrest the leaders. The people attacked the police and they ran away. When more police tried to break up a meeting on October 18, led by a lieutenant named G.B. Singer, they attacked Singer, based him on the head, and threw him the river, killing him.

This led to murderous violence by the British. This new rebellion did not last too long. A major named Henry Hopkinson happened to be nearby. He heard about, took a boat, recruited some soldiers, and just opened fire on the farmers. They killed 39 right away and 15 more died in the coming days from their wounds. Two more British soldiers died too. That put the uprising down. Of course in the coming months, the British forced the local Indians to supply the Army with food and housing while the occupied the area. Three leaders were executed and several others imprisoned or shipped out to Australia.

This is just a minor moment in the history of the resistance to British colonialism, but it demonstrates how brutal the British were to the workers in India. This would hardly be the last time Indian anger over British domination would manifest itself.

This is the 498th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.