Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,467

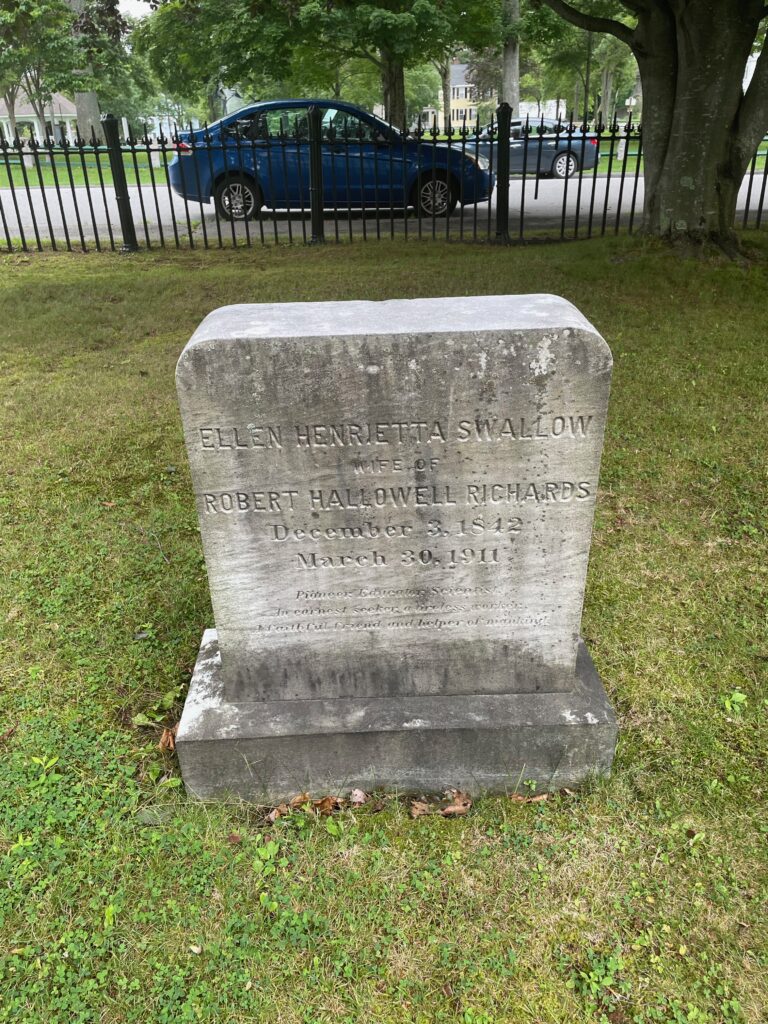

This is the grave of Ellen Swallow Richards.

Born in 1842 in Dustable, Massachusetts, Ellen Swallow grew up in a middling family of farmers who did not have a lot of wealth but who believed strongly in education for both boys and girls. She was their only child. She was home-schooled for awhile and then the family moved so she could to go Westford Academy in the town of Westford, which was an early public school. She had the classical learning of her time, including multiple languages. She finished there in 1862 and was going to teach. But a severe case of the measles changed her plans. She spent the next couple of years on and off teaching and taking care of her aging parents. But in 1868, she decided to go to Vassar, the early women’s college. Given her age and advanced training, she was sped up through the school and graduated in 1870. She stayed for a master’s degree and started working heavily in the sciences, particularly chemistry. She got special permission for another advanced degree at the precursor to MIT. In fact, she was the first woman admitted into that school. She finished a bachelor’s degree there in 1873 and did graduate work too, but the school just wasn’t ready to give a master’s degree to a woman. While there as well, she met Robert Richards, a mining engineer and MIT professor. They married. He supported her work and made sure she could teach at MIT. But she couldn’t get paid for that. Nope. She had to volunteer.

Well, Richards would become one of the nation’s top scientists, regardless of gender. Her specialty was sanitary chemistry, which is an early term for what today we would probably call environmental chemistry or some such thing, in any case she was particularly interested in issues of pollution and how they impacted people. She particularly became an expert in issues of clean drinking water. This was in the 1880s and it was around issues like that well-educated women were finding niches in the male supremacist workforce. In 1885, Jane Addams created the first American settlement house. She and her followers basically invented social work and looking after women and children became a space where women could operate since most men wanted nothing to do with it. It was similar for industrial hygienists such as Alice Hamilton, who could use respectable Gilded Age Victorian values to go into workplaces and tell employers that poisoning workers was wrong and here’s how you could not do that. Richards was in the same boat. The scientific establishment wasn’t going to let her work on most issues. But if she wanted to do some kind of science that was caregiving, such as clean water issues, well, OK, most male scientists were more concerned with developing profitable means of using water to pollute and thus create progress.

So Richards helped open the Lawrence Experiment Station in that industrial Massachusetts and was involved in its beginning in the mid 1880s (for some reason the exact date of opening differs depending on where you look, but either 1884 or 1887) to her death. She also finally got a paid job at MIT in 1884 teaching about sanitary chemistry in the school’s new lab on the topic. One of the first things she did was work with the state to test water quality in a comprehensive way throughout its communities. This led to the first real water quality standards in America and the Lawrence sewage treatment facility, again, the first of its kind in America.

Working on educating women, Richards then wrote popular science books for the home that would help bring basic scientific techniques into things such as cooking and cleaning that women could easily digest and then use. These include The Chemistry of Cooking and Cleaning in 1882 and Food Materials and Their Adulterations in 1885. That last one led the state to pass a pure food act, twenty years before the federal government got around to it after Upton Sinclair published The Jungle. She generally tested all this stuff in her home. She did things like create more ventilation and more from dirty coal to gas heat. She also tried to create a scientific field called euthenics, or the science of better living, but this sounded so much like eugenics that it never did catch on. But I think the important thing here is that she was working to make what became home economics into a serious field of scientific inquiry and she didn’t really succeed at that. The home economics people tended by later in her career to leave the scientific stuff to men and the scientists didn’t have much interest in the home. But that’s hardly Richards fault. What more was she supposed to do?

Interestingly, the other scientific word Richards pioneered had a lot more staying power–“ecology.” To be fair, she did not actually invent it. It was invented by the German scientist Ernst Haeckel. But Richards was the first person to use the term in a book written in English. And they say scientists don’t need to learn humanities or languages!

Now, like a lot of these other early women in the professional fields, Richards consciously played on her traditional gender norms to justify what she was doing. So to consider her creation of home economics, she herself stated,”Perhaps the fact that I am not a radical and that I do not scorn womanly duties but claim it as a privilege to clean up and sort of supervise the room and sew things is winning me stronger allies than anything else.”

But Richards was also a strong feminist and worked to develop powerful institutions to improve women’s lives, many of which remain around today. For example, she was one of the founders of the American Association of University Women. My wife received an AAUW fellowship that paid for her year of research as a PhD student in Mexico she needed to write her dissertation, as an example. It wasn’t just elite women that interested her either. She created a test kitchen in Boston to experiment on how to thread the needle of making meals tasty, cheap, and healthy so that working class families could eat well too. As for what she was trying to do here, here is a long quote from a forward she wrote to a book about the project:

The story of the New England Kitchen … is remarkable for two things: the new and valuable information which has been acquired, as the result of the daily work of the Kitchen, and the short time which has sufficed to put the enterprise on a business basis.

It is well to emphasize the causes of this success, that the lessons in social science and practical philanthropy be not lost. A large part of the credit is due … to Mrs. Abel’s hard work[.] [S]tarting the New England Kitchen … was … an experiment to determine the successful conditions of preparing, by scientific methods, from the cheaper food materials, nutritious and palatable dishes, which should find a ready demand at paying prices.

Mrs. Abel would doubtless give as the principal secret of her success, that she had everything necessary for the experiments, without giving a thought to the cost. … In the New England Kitchen, the selection of the apparatus and material and the employment of labor have been without restriction. Without this freedom to carry on the experiments as seemed wise and prudent, the results detailed in the accompanying report could not have been attained.

The philanthropy of the scheme rests in the experimental stage of the development of the New England Kitchen. Whether the business can in the future take care of itself to the profit of those who conduct it remains to be seen ; but, in any event, kitchens of this kind cannot fail to be of great advantage to multitudes in moderate circumstances, who have hitherto been unable to buy good, nutritious, and tasteful cooked food.

Out of this, Richards even had her own booth at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, part of the famed White City there. Moreover, she pioneered the idea of free school lunches for working class kids. This started in some Boston schools in 1894. The national free lunch program did not happen until Truman signed the relevant legislation in 1946, but this was a critical antecedent and built support for the idea. She also founded and was the first president of the American Home Economics Association, in 1908.

Richards worked up to the point of her death. Her last book was Euthenics: The Science of Controllable Environment, which was published in 1910. She died in 1911, at the age of 68, after suffering from angina.

Ellen Swallow Richards is buried in Christ Church Cemetery, Gardiner, Maine.

If you would like this series to visit other presidents of the American Home Economics Association, which today is known as American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Lord knows I have plenty of them from this week in Los Angeles. I am up to having visited about 125 graves now. Isabel Bevier is in Plymouth, Ohio and Sarah Louise Arnold is in Abington, Massachusetts. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.