Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,455

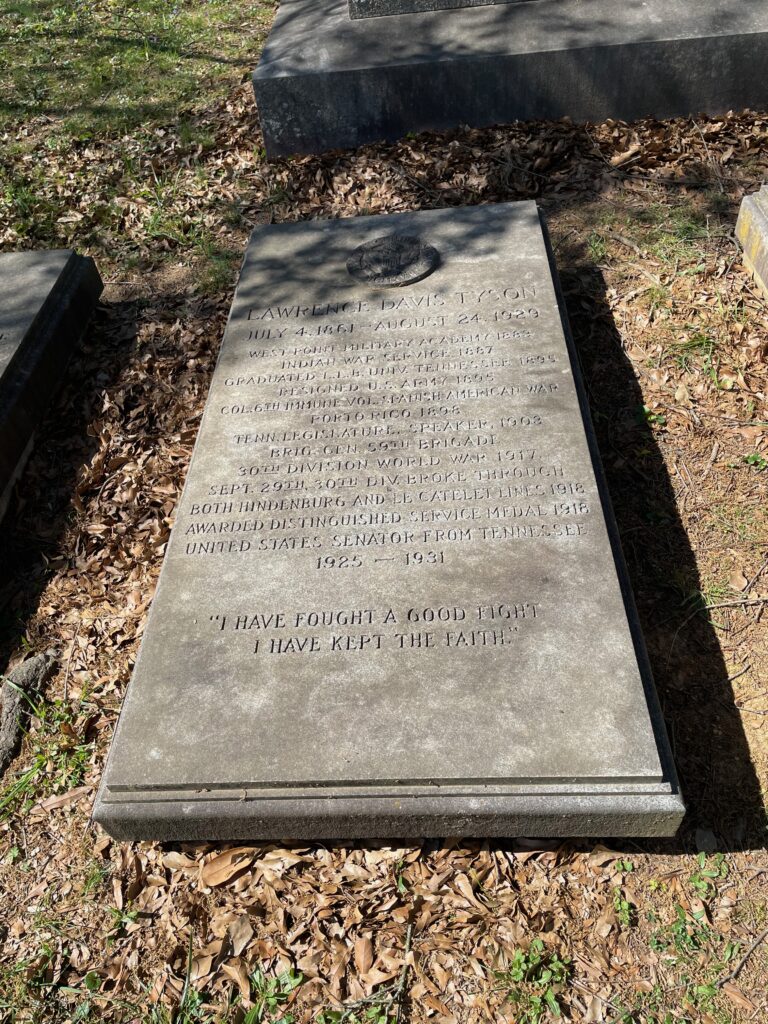

This is the grave of Lawrence Tyson.

Born on a farm outside of Greeneville, North Carolina in 1861, Tyson came from a relatively wealthy farming background. His father owned 21 slaves in 1860 and even though he was more a working farmer than a planter, that was a lot of human property. Of course, the family lost all this property in 1865 and received no compensation, as was morally correct. Tyson was working as a clerk as a young man when he took the entrance exam for the U.S. Military Academy in 1878. He basically aced it and won himself an appointment at West Point. He finished there in 1883 and was involved in some of the late genocidal wars against the Apache in Arizona. He then married the daughter of the wealthy railroad tycoon Charles McGhee, who was the big capitalist in Knoxville, Tennessee. Tyson may have grown up fairly middling, but a young army officer and clear rising star was marrying material for the daughter of a rich guy. McGhee then got Tyson named as a professor of military science at the University of Tennessee. He enrolled in UT’s law school at the same time. He didn’t want to be a career military guy. He finished there in 1894 and then resigned his military commission.

With both a military and legal background, Tyson was well set up to go into politics. He got to know Edward Sanford and worked as his clerk, though this was before Sanford was on the Supreme Court. Tyson did return to the military in 1898 as part of the imperialist invasion of Cuba and other Spanish possessions. What better way to improve your resume? Theodore Roosevelt certainly saw it that way. Tyson was in Puerto Rico so there wasn’t much fighting. Just a good ol’ imperialist occupation that still continues today. He came back and in addition to his law practice, opened some textile mills at the same time that northern employers were looking to escape from their workers organizing. Interestingly, he also had some reform tendencies and was part of attempts to get rid of child labor in his state, which was a big reason why those companies were moving there in the first place. But to be clear, Tyson was employing children too. He wasn’t going to give up a competitive advantage. He just wanted everyone to do this at the same time. In fact, when Lewis Hine came down to the South to take his famous pictures of child workers, some of them were in Tyson’s Knoxville Cotton Mills facilities.

Tyson was also part of the Democratic dominance of southern politics. Tyson was a classic New South figure, in that he preferred to talk about development while also completely supporting and benefiting from excluding Black Tennesseans from politics. He entered the state legislature in 1902, shortly after the 1899 laws effectively ending Black electoral politics in Tennessee for the next seven decades. He immediately became Speaker of the House for his only term in the body. He secured state funding for the University of Tennessee in Knoxville for the first time. Given Tennessee’s present funding of education, who knows how long that will last….He really wanted to be a senator though, but never got chosen by the legislature, despite his attempts to do so. So he went back to Knoxville, ran railroads, his cotton mills, and other businesses, and led the life of an elite figure in a mid-sized southern city.

When the U.S. entered World War I, Tyson saw another opportunity to serve his nation and advance his political career (again, there’s no real contradiction here) and so he volunteered, even as he was in his late 50s. He was named a brigadier general of the Tennessee National Guard by the governor and the troops under his command entered Belgium in July 1918. In fact, they saw some serious action in the last months of the war, being on the front lines of the final push against Germany. By this time, these particular troops were under Major General Edward Lewis and in fact functionally under British command, but whatever, no one was going to hold any of this against Tyson. They were active in the Somme and really saw very heavy fighting and casualties. The bravery of these soldiers–about 1800 casualties out of 8000 troops–made them heroes back in Tennessee. Tyson received the Distinguished Service Medal for his actions in the war. Then, as soon as the war ended, Tyson went out to find the body of his son, who was killed in the war. So he suffered too.

Tyson came back and he wanted high political office. He lobbied for himself to get the VP nomination on the 1920 presidential ticket but that didn’t happen as James Cox picked Franklin Delano Roosevelt instead. So he went back to Knoxville, bought the Sentinel, the city’s largest paper, and used it as a springboard for a Senate run. Now that it was popularly elected, he could do this and he won election in 1924, defeating the anti-League of Nations isolationist John Knight Shields in the Democratic primary, which is all that mattered in a one party state. The real challenge he faced was not the general election, but from enemies within the Democratic Party after the election, which claimed that he violated the law by self-funding his campaign to unprecedented levels (this was more or less true in terms of the self-funding, but the legal side of it was much less clear. Basically, they claimed he bought his election and wanted the Senate to throw him out. Tennessee’s other senator, Kenneth McKellar, was a bit concerned about what really happened, but figured the evidence wasn’t enough and just let it go.

Tyson was a pretty active senator, doing a lot of work on disability programs for veterans and laying the groundwork for the creation of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. He also supported American internationalism. His first speech in the Senate was supporting American participation in the World Court. Of course Calvin Coolidge, being a cheap stingy bastard, vetoed the Tyson-Fitzgerald Act that provided disability benefits for injured part-time officers (people like himself, regular Army officers already received them), but Tyson rallied the Senate to override the veto. But Tyson wouldn’t even get one term. His health began to fail. He checked into a sanitarium in Pennsylvania but never got out. He died in 1929, at the age of 58.

Lawrence Tyson is buried in Old Gray Cemetery, Knoxville, Tennessee. I am amused that this very chatty stone says he was in the Senate until 1931 even though he died in 1929.

If you would like this series to visit other senators elected in 1924, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Thomas Schall, primarily remembered for being hit by a car, is in Minneapolis, and Charles Deneen is in Chicago. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.