Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,445

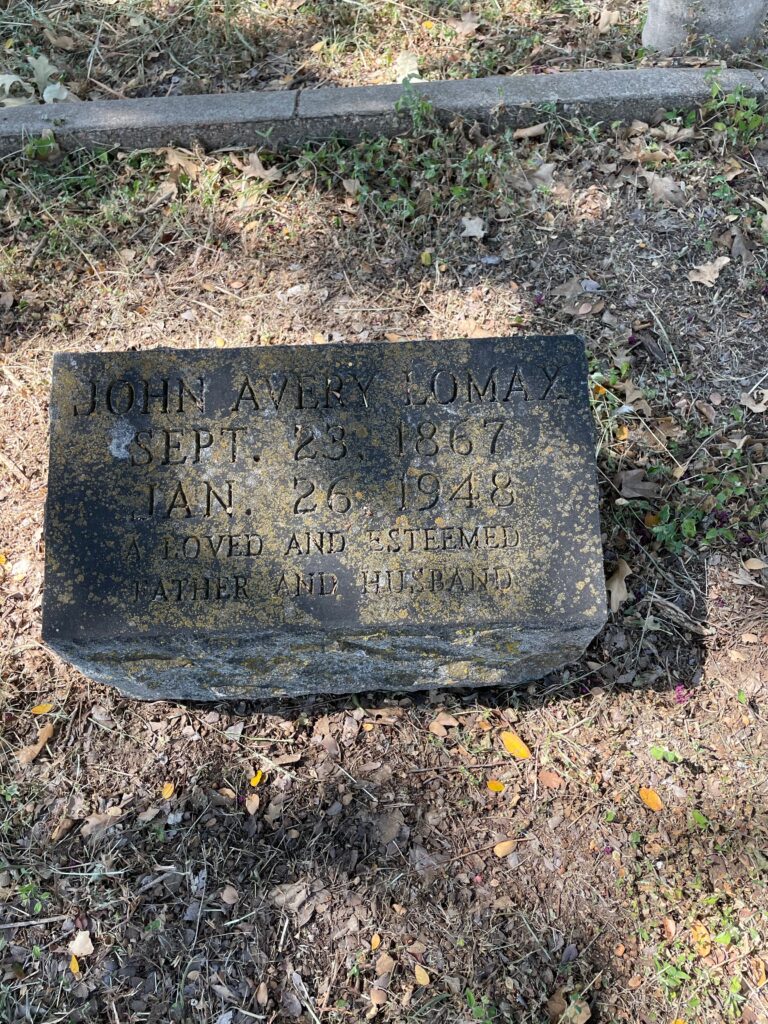

This is the grave of John Lomax.

Born in 1867 in Holmes County, Mississippi, Lomax grew up in Texas to a farming family. His father was a reasonable successful farmer, though nothing crazy. But his father, who mostly raised cattle, hired cowboys and those cowboys sang. Lomax hung out with these guys and learned to love their songs. He was the kind of white kid who “befriended” one of his father’s Black workers. What the worker thought is not something we can know, but in any case, Lomax thought this and it became part of his origin story. At the very least, Lomax claimed he taught the guy how to read, so if that’s true, then OK, that’s a good thing. After working very hard on his father’s farm as a kid, Lomax paid his way through Granbury College, taught in a local school for a bit and hated it, worked at Weatherford College for awhile as the head of the Department of Business, and traveled to New York in the summer for time at the Chautauqua Institute to improve his overall education, which despite working at whatever passed for colleges in rural Texas, was spotty. In 1895, that led him to enroll at the University of Texas in Austin to get a real degree. He graduated in 1897 and became the school’s registrar. He stayed there until 1903, then took a teaching job at Texas A&M while also doing graduate education at Harvard in the summer.

Harvard changed his life because unlike all the other educated people he had met, his mentors there encouraged his personal interest in cowboy songs. He brought them a bunch and they thought they had significant folkloric potential. One of his mentors was George Lyman Kittredge, who was a major folklorist of English traditions. Kittridge encouraged Lomax to start collecting stuff. So when Lomax went back to Texas, he did. In 1910, he published Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads and somehow the publisher got it into the hands of Theodore Roosevelt, who wrote an introduction for it. Lomax was most certainly not without his racial biases. Anyone who listens to his field recordings notes the utter condescension toward Black musicians he felt. But he also was sure to emphasize the Black contribution to this folklore. For example, he noted in his book that “Home on the Range” came from Black cowboys, even though later it was copyrighted by whites because of course it was.

A lot of these songs are considered standards today, but they could have been lost without Lomax. He made the first recordings of “The Old Chisholm Trail,” one of the real classics of American folklore, after hearing a couple of cowboys singing it in a Fort Worth bar. A woman living in a truck outside Fort Worth provided him with “Git Along Little Dogies.” An old hunter from the 19th century living near Abilene gave him “Buffalo Skinners.” There is no good reason any of these songs survive today and yet they do because of John Lomax.

This book made Lomax a well-known figure in intellectual circles, which was his life goal. He was elected president of the American Folklore Society in 1912. He married and had a few kids, including his son Alan who famously followed in his father’s footsteps. He published Songs of the Cattle Trail and Cow Camp in 1919. Things were not necessarily easy for Lomax though because of politics. At this time, like Ron DeSantis is trying to do today, governors were directly involved in who worked at universities and James “Pa” Ferguson and Lomax very much did not get along. Ferguson had Lomax fired twice and finally the latter just took a job in a bank to make ends meet while working on his passion. Things weren’t great in these years. His wife died, then the bank failed during the early years of the Depression.

Finally, at the encouragement of his son John Jr., Lomax went to New York and sold to Macmillan Publishing the idea of a giant book of American folk song. This worked and Lomax started hitting the South, recording whoever he could find. Then he went to the Library of Congress, which was considered the center of American folk song collecting. But Lomax told the Library that their collection was terrible. So they put him in charge of it. With Alan in tow and making a nominal salary, John hit the road to improve it. He went to the fields, the cities, and the prisons of the South. Dragging a 315 pound recorder in the trunk of their car, they managed to make some of the first important recordings. Most famously, this included finding Leadbelly in the Angola Prison in Louisiana in 1933. Leadbelly and Lomax would have a long association and helped both, the former in getting him gigs in the burgeoning folk scene around the country after his release and the latter through making the profit. Lomax also hired Leadbelly as his driver upon his 1934 release. But Lomax was totally paternalistic to Leadbelly, leading to the latter chafing against the white man and going out on his own pretty quickly and staying there.

So Lomax was a problematic guy, who wanted to shape Black music as to his perceptions of Black culture, which meant a big emphasis on primitivism and romanticizing poverty. But then no one else was even recording this stuff at the time so he also did so much work to allow us to hear these songs today. Lomax hired other folklorists and archivists to record stuff they could find, not only in the U.S. but in the Caribbean. These included people from Bascom Lunsford to Zora Neale Hurston to lots of others largely unknown today. This was funded by Congress and that ended in 1942 because the right-wing racist southerners in Congress began to believe this was all a plot to push civil rights. Meanwhile, Lomax also worked with the Works Progress Administration as an advisor on the Federal Writers Project and the Historical Records Survey. Some of this work included directing the oral histories of people who remembered slavery. I cannot emphasize how critically important this work is. These oral histories still are the most important documents we have for first hand accounts of slavery. Historians of the topic use these oral histories all the time.

In 1947, Lomax published his memoir Adventures of a Ballad Hunter. This was supposed to be made into a Hollywood movie with Bing Crosby as Lomax and Josh White as Leadbelly but thank God it was never made because I have no way to conceptualize this except as a disaster. Lomax died in 1948 of a stroke. He was 80 years old.

John Lomax is buried in Oakwood Cemetery, Austin, Texas.

If you would like this series to visit some of the folklorists Lomax worked with, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Zora Neale Hurston is in Fort Pierce, Florida and Ruby Pickens Tartt is in Livingston, Alabama. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.