Policy-Blogging: A History of Progressive Inflation Control – The Macunian Tradition, Keynes’ Plan to Pay for the War, and John H.G Pierson

Introduction

Following up from my post on price controls, I wanted to talk about another progessive tradition of dealing with inflation.

The left had a major breakthrough in 2020 and 2021 where the state really did spend at the levels we were demanding, and provided unprecedented levels of income supports and social spending. This had major (and seriously underrated) effects on incomes, poverty, unemployment, and economic growth. However, the left did not quite achieve the kind of institutionalizing success it was looking for – MMT’s principles were not enshrined into law, the Sahm rule was not enacted by either the Fisc or the Fed, and Manchin even killed the expanded child tax credit.

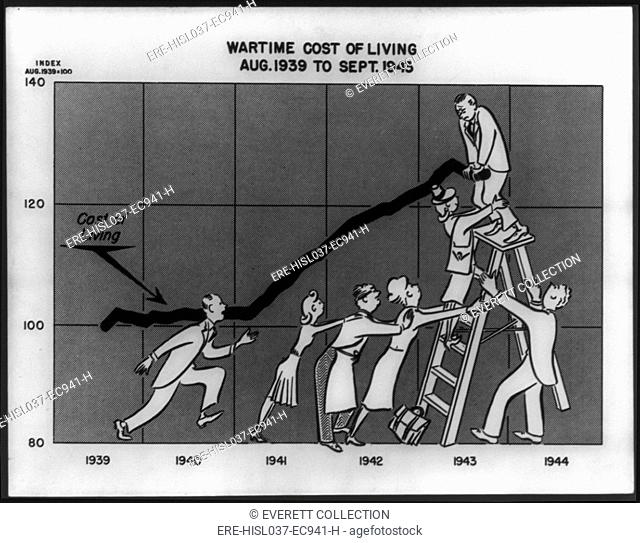

Then inflation really hit and the economic establishment launched a counter-offense, blaming inflation on over-stimulating the economy. With further fiscal policy prevented by the Republican takeover of the House, the Fed had all the political cover it needed for its eighteen-month-long campaign of interest rate increases that Powell and others have talked about as intended to squash wage demands from an increasingly militant working class. Even after runnning into real trouble with bank failures due to the impact of higher interest rates on the more speculative end of investment (crypto, bets on t-bills and interest rates, other kinds of illiquid assets).

The same phenomena can be seen in Europe, where Boris Johnson and Liz Truss’ supply-siders were ousted by the austerity wing of the Tory Party and Starmer’s Labour Party is jettisoning its own climate proposals to avoid being out-flanked on “fiscal responsibility.”

In this moment, the left has not unified around a common program for fighting inflation that could serve as an alternative to austerity. Voices on the left, whether it’s heterodox economists in MMT or their post-Keynesian brethren or progressive electeds like Bernie and Warren have been talking about inflationary stagnation, speculative asset inflation, and greedflation/excuseflation, and industrial policy, but rather than coming to a consensus, our efforts have been scattered and rather difficult to elevator pitch to the public.

This is historically a problem for the left – we have a tradition that gives us a clear playbook for economic downturns, but we run into difficulties when we try to do full-employment social democracy in a time of inflation (whether that’s Attlee, Truman, the Great Society, or Carter).

As I suggested in my previous post on price controls, part of that has to do with the fact that parts of our intellectual tradition were lost, either in the end of the New Deal era and the rise of the Red Scare in the 1940s in the American case, or in the end of the trente glorieuse and the rise of neoliberalism in the late 1970s in the European case.

In this follow-up piece, I want to recover another lost intellectual tradition: counter-cyclical planning. Thanks to Zach Carter and Robert Skidelsky and Richard Parker, we know this history when it comes to counter-cyclical planning aimed at ending the Great Depression and making sure another one could never happen. What we don’t talk about (as much) is the other side, the version from the Upside Down: counter-cyclical planning to prevent inflation.

Ever-Normal Granaries

While we think of this kind of economic interventionism as inherently modern, the reality is that pre-modern states had little choice but to try and deal with the original crisis of price stability: bread prices. As Bret Devereaux points out in his excellent series on the history of grain production, ensuring a stable supply of grain was an absolute necessity for the survival of the state. If the grain harvest failed, you didn’t just get famine and plague, you got war too: peasant rebellions in the countryside, bread riots in the cities, banditry and warlordism in between as the troops you could no longer afford to pay used their swords to get themselves paid, and soon foreign invasion when your state’s weakness was laid bare for the world to see.

At the same time, plenty could present its own problems. As I’ll show later, one of the unchanging truths of agricultural labor is that the farmer got the wrong end of the stick in both times of shortage and prosperity, because of the extreme difficulty of coordinating output with other farmers. If everyone got a bumper crop, in addition to the difficulties of storing agricultural surpluses over the long-term, farmers faced radical drops in prices that could reduce their incomes below their fixed costs. While subsistence farmers were somewhat shielded from this effect by their policy of autarky-through-home-production and rent generally paid as a share of the crop rather than in money terms, more commercial farmers within easy distance of the city who were more likely to operate through formalized structures of debt and money rent could be ruined.

One of the oldest and most widely-adopted measuress to deal with this paradoxical dilemma was the “ever-normal granary.” One of the first buffer stock schemes in world history, this policy involved the creation of public granaries that would be used to buy surpluses when prices were low – thus providing a floor on the price of grain – and then sell them at below-market prices in times of crisis to ward off mass starvation, thus providing a ceiling on the price of grain.

While we have historical evidence for ever-normal granaries in quite a lot of the ancient Middle East – there’s a reason why those Bronze Age palace-and-temple complexes all included storehouses as a major part of their planning system – the most attested case study of the ever-normal granary, and indeed the source of its name (“Chang-ping-can“), comes from China across a period of almost two thousand years. As R. Bin Wong puts it in “Chinese Traditions of Grain Storage:”

“Granaries have a long history in China. The inspiration for them is found in classical texts, which placed political commitments to grain storage within a larger program of “nourishing the people” (yang min). The establishment of granaries was a recurrent phenomenon during the entire period of imperial rule. From classical precepts to late imperial practices, the storage of grain satisfied basic political ideals and urgent practical needs.”

As far back as the Warring States period, the ever-normal granary was a major concept of Legalist thought-

“Li Kui, the legal thinker responsible for the Classic of Law, worked out the logic of state intervention, saying that rulers should buy and sell grain to inhibit price fluctuations since high prices harm consumers and low ones harm producers.”

“Mencius explained the general importance of a stable material existence to morality in this way: “As to the people, if they have not a certain livelihood, it follows that they will not have a fixed heart. And if they have not a fixed heart, there is nothing which they will not do, in the way of self-abandonment, of moral deflection, of depravity, and of wild license.”4 The Guanzi, a Han-dynasty collection of materials written over the preceding several centuries, cogently defines the close links between grain storage and popular morality: “When the granaries are full, [the people] will know propriety and moderation; when their clothing and food are adequate, they will know [the distinction between] honor and shame.”

Rising to its height during the Qing dynasty in the 17th century, the ever-normal granary was established nationwide at a scale of 2.2-3.3 million tons of grain, supporting almost 100 million people. The success of the ever-normal granary was the foundation of the health of any given dynasty, and its collapse during times of rebellion brought famine and plague in its wake.

Macune, the Sub-Treasury, and Henry Wallace

Through the Commercial and Industrial Revolutions, more and more economic producers both in manufacturing and agriculture were brought into ever wider spheres of competition, and thus exposed to the same boom and bust cycles. In the 19th century U.S, the Populist movement was the first to deal with a uniquely capitalist farmer’s dilemma. Thanks to the telegraph and the postal service, the loans they needed to operate as commercial farmers were now held by banks in New York and London; thanks to the railroad and steamship, they were now part of a world market, so abundance abroad could become price deflation at home – this combination of highly fluctuating prices and increasingly fixed debt and transportation costs exposed all of them to potential destitution.

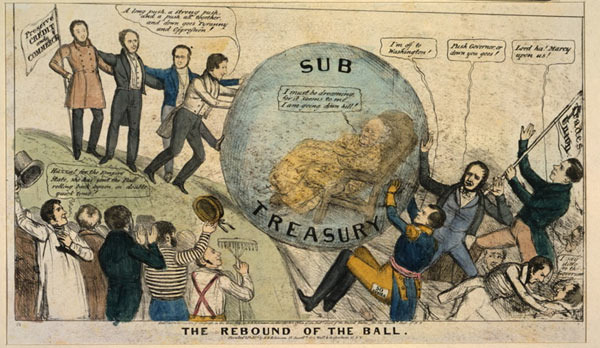

The barrier to doing something about this instability through the political system is that rural small farmers seemingly had inextricably hostile interests to the urban working-class, where high prices (and thus high real incomes) for the one meant economic devastation of the other. To solve both the economic problem of the farmer and the political problem of the worker, Charles Macune of the Farmer’s Alliance proposed the Sub-Treasury Plan.

Just as with the ever-normal granary, the sub-treasury was a network of government warehouses where farmers could store agricultural commodities when prices were low in exchange for low-interest Treasury notes, which they could then redeem to pull their commodities from the warehouse to sell when prices were higher – thus putting a floor under farmer incomes but also a ceiling on agricultural prices to protect the urban consumer.

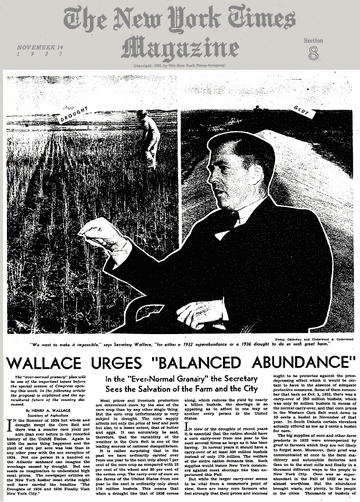

Thus, it really mattered that when FDR chose Henry Wallace to be his New Deal agriculture czar, Wallace happened to be a man with Populist and Progressive Party roots as well as a trained agronomist who had studied the history of the ever-normal granary in China.

Thus was born the basic principles of New Deal farm policy: direct agricultural subsidies to provide a government check as a floor on farm incomes, in return for production restriction that would raise prices for agricultural goods, combined with government surplus commodity programs that redirected agricultural products that would have otherwise been destroyed to the rural and urban poor who couldn’t have (the origin of both the modern Food Stamp system and “government cheese”).

When taken together with the New Deal’s policies on industrial price control, I think we can speak of a coherent policy regime of controlled prices through tripartite bargaining and planning.

Keynes’ Plan to Win the War

As we move away from the older history of agricultural price control into a more recent history of attempts to control prices across the whole of the economy, I want to bring in John Maynard Keynes. If you’ve ever read Keynes himself, or any of the excellent recent biographies of Keynes by Robert Skidelsky or Zach Carter, you’re probably familiar with the way that Keynes’ General Theory centered the economic imagination around the counter-cylical planning of demand through the use of fiscal and monetary policy and the possibility of achieving long-term full employment and the end of the business cycle.

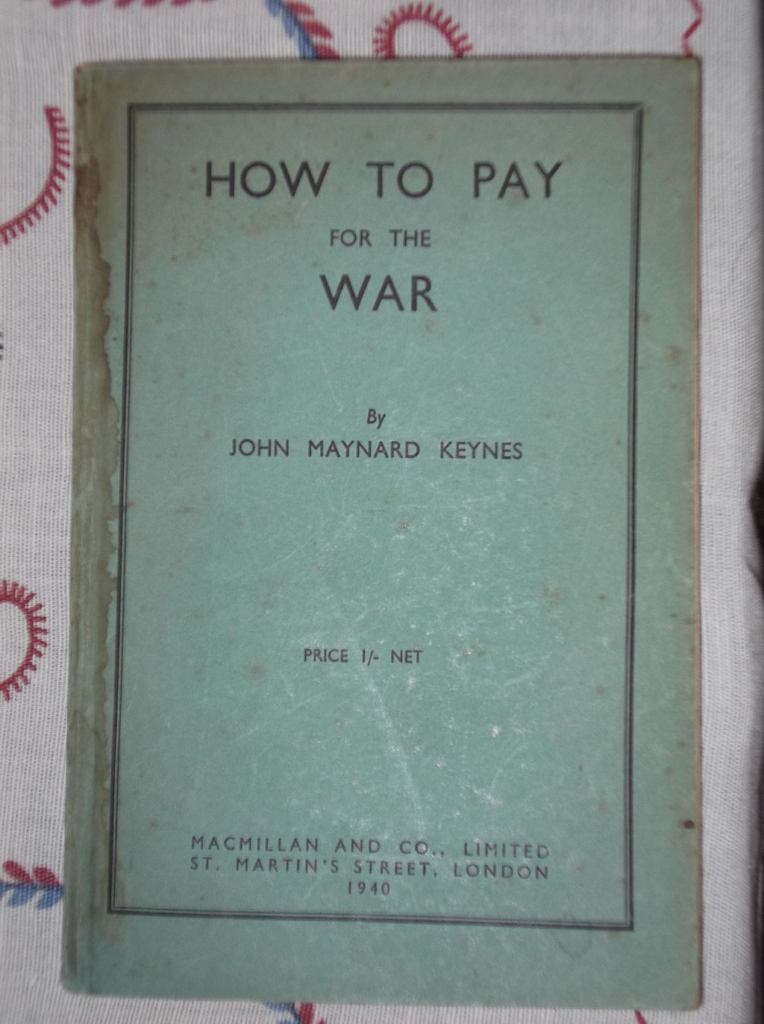

But Keynes didn’t stop publishing in 1935, and when World War II started, Keynes as a classic academic-turned-civil servant in the British model went back to working for the government, to harness his economic theory to the task of full production to defeat the Nazis. In 1940, Keynes put out a new book entitled “How to Pay for the War.”

In this manuscript, Keynes adapted his counter-cyclical planning to a new economic environment in which the economy was producing at full capacity and full employment, but needed to restrain inflation that could explode if British trade unions channeled the frustrations of a lost economic decade into full-throated demands for higher wages. Keynes’ proposal sought to combine wage controls and free collective bargaining (two things you’d think were inherently at odds) through forced bond-purchasing. In this policy regime, unions would be free to use tight labor markets to win wage concessions from industry, but wage gains above a level consistent with contained inflation would be given out in the form of bonds that would only mature after the war.

In this fashion, Keynes believed that the state could shift demand through time from a period of excess demand like total war-time to a period of insufficient demand, like demobilization after a world war. Wage-bonds would ensure that consumer demand could take over from war spending and ward off a second Great Depression in favor of permanent prosperity.

However, as Steven Fielding et al. point out in England Arise, when Keynes presented his proposal to the trade union movement and the Labour Party, they initially balked at it. Trade unionists feared that this system might be gamed by conservative governments at the behest of employers in order to restrain wage growth; Labour Party officials and MPs had more of an economic commitment to nationalization and more statist methods of economic planning. Much in the same way that they would only pick up William Beveridge’s banner of full employment throught the welfare state after the Beveridge Plan was a proven success with the public, the “thermostatters” among the planners of the Attlee government only adopted Keynesian economic planning afrer they saw it working during the War.

As Parker, Skidelsky, and Carter have pointed out in their biographies, not all of Keynes’ ideas made it into the “postwar Keynesian synthesis” that social democrats and progressives on both sides of the Atlantic adopted as their economic faith. As with the ideas of post-Keynesians like Kalecki and Minsky, Keynes’ own ideas about how to control inflation through bond-purchasing and shifting demand through time were not part of the intellectual toolbox available to social democrats confronting the end of the trente glorieuse and the rise of staglation.

John H.G Pierson

However, I didn’t want to leave the topic of progressive inflation control without talking about an unheralded homegrown economist, John H.G Pierson. One of the economists involved in crafting the 1946 Employment Act, Pierson was one of the full employment planners I covered in chapter 4 of my book. Much like his committee staff colleague Leon Keyserling, Pierson also put forward a plan for post-war full employment as part of the Pabst Blue Ribbon competition in 1945.

While Pierson’s proposal included both provisions for New Deal-style direct job creation (following the proposals of the National Resources Planning Board) and counter-cyclical economic planning borrowed from Keynes’ General Theory, the truly distinctive component of Pierson’s work was a more consumerist approach to full employment.

Rather than solely relying on government spending and the multiplier effect to stimulate demand, Pierson wanted the government to influence the activity of the American consumer through counter-cyclical systems of taxation and subsidy. The centerpiece of this design was a national sales tax whose rate would be constantly adjusted by the Federal government in order to promote consumption; Pierson explicitly stated that this rate should be allowed to go into the negatives if necessary, thus bringing prices down (and thus consumption up) by main force.

Conclusion

Whether it’s the ever-normal granary, the Macunian tradition of the Sub-Treasury Plan, Keynes’ mind-blowing idea of shifting demand through time, or John H.G Pierson’s reversible taxation, there is a rich history of progressive inflation control that the contemporary left can use as a shield to go along with the sword of spending. We just have to do a better job of knowing where to look and what histories to tell ourselves.