Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,427

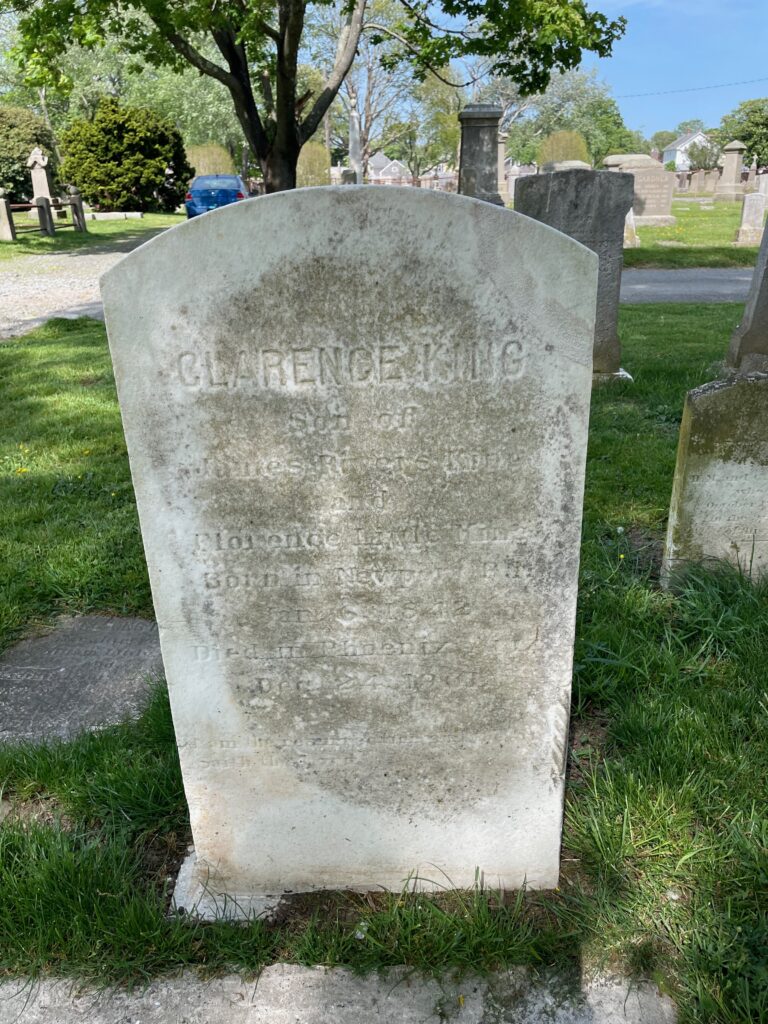

This is the grave of Clarence King.

Born in 1842 in Newport, Rhode Island, King grew up in the trading class out of that town. His father was heavily involved in the China trade and young Clarence barely knew him before the father died in 1848. His mother sent him to a school in Connecticut and there he became interested in the natural world, which was encouraged by his teachers. After a childhood of moving around between schools and trying to survive on what his father had left the family, things turned up in 1860 when his mother remarried a rich guy, who then paid for King to attend Yale.

While at Yale, King was initially interested in chemistry but soon read about the new field of geology and became increasingly interested in it, especially after attending some lectures by Louis Agassiz. He got some of his friends to go with him to the West and they departed in 1863 (one assumes here King bought his way out of the Civil War; he was an ardent abolitionist for awhile, but seems to have not been so ardent when fighting was involved). When they got to San Francisco, King volunteered to work for the California Geological Survey for free to start. A long career was born. Much of this early work was just exploring various parts of the Sierra Nevada, which was a ton of fun but also pretty dangerous since these were rugged mountains and no one really knew what was up there.

But King wasn’t just an explorer. He was very much a man of his time period and he wanted to connect up this science with the ability to develop the country for the capitalists coming to dominate the country at this time. With the railroads expanding west, King knew that they would want to make money on the huge land grants the federal government gave them to incentivize the building. So if he could find valuable minerals on them, he could make it pay for everyone, including himself. Now having a lot of connections, King went to Washington in 1866 to make the case for a federally funded geological survey of the Great Basin, which naturally King would lead. He succeeded and spent most of the next twelve years traipsing around the West working on it. He also published his first book, Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada, in 1872, which was a popular book on his explorations. He soon became the expert on this region. In 1872, for instance, the greed-hungry America heard news of a huge diamond strike in Colorado. It was a total hoax foisted by a couple of guys who planted diamonds in the soil and then tried to get rich businessmen to “invest,” but people started going there anyway to mine. King headed up there, definitively called it a hoax, and killed the whole thing. This made him much more famous.

In 1879, Congress created the U.S. Geological Survey and named King its first director. Now, this was an interesting life in a sense. Most of these early USGS geologists, including King, were elites or near elites. They were well educated men, usually with a lot of social connections back east. But the lives they were lived were hard. Nevada wasn’t some nice place. Most of these men were on the look out for mining prospects themselves and those mines were usually in the middle of nowhere–hot, dry, isolated. Would they ever pan out? Well, occasionally. But usually, these men just spent years and years of their life away from the society where they came from. Wallace Stegner‘s Angle of Repose, despite having the worst ending of any major book in the American canon, is pretty masterful on exploring this issue and its impact on families. When he was at home, King was a true elite–he invested in art and liked nice things. He was buddies with elites such as John Hay and Henry Adams. But his personal fortune was based on him trying to get that silver or whatever out of some obscure mine in Idaho to pan out. It usually didn’t work and he was perennially short on money.

Now, King never married. He settled in New York eventually and lived the best social life he could. But the story of his love life is…complicated. In about 1887, he fell in love with a younger woman named Ada Copeland. She was a former slave, born in Georgia in 1860 and who ended up working as a maid in New York. Of course this would lead to massive complications. This was a racist society after all. King could not expect his friends to accept her. But the choice he made was an unusual one. He decided he would live a double life and pass as a Black man. Now, understand that King was not a dark man. He had blonde hair and blue eyes. But what did that mean in America? He never told her he was white until the moment of his death. He claimed his name was James Todd and he was a Pullman porter, which is why he was gone so often, when in fact he was in his fancy home with his fancy art hanging out with his fancy friends in a different part of New York. They had five children. It was only upon his death, when he was out in Arizona in 1901 trying to recover from tuberculosis, that he wrote her a letter telling he his name and saying that he had a trust fund for her. He died at the age of 59.

The story of his family does not end there. I don’t know exactly how King’s friends saw this of course when they found out about it. Some of them might have even known something before. But the case of the trust fund would wind through the courts for the next 32 years and it wasn’t until 1933 that the courts finally definitively denied her the trust fund, saying that King had no money left after his debts were paid. This became a pretty big case and she was represented by the top Black lawyers of the day. Meanwhile, his friends actually did look after her. John Hay, who by this time was Secretary of State, gave her a monthly stipend for years. As for their four surviving kids, the two boys both fought in World War I as Black soldiers. The two daughters passed as white and married white men. Ada Copeland lived all the way until 1964, when she was 103. She was among the very last living Americans who had personally experienced slavery.

Ah, race in America.

Clarence King is buried in Island Cemetery, Newport, Rhode Island.

If you would like this series to visit other American geologists, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Joseph Barrell is in New Haven, Connecticut and Thomas Crowder Chamberlin is in Beloit, Wisconsin. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.