Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,415

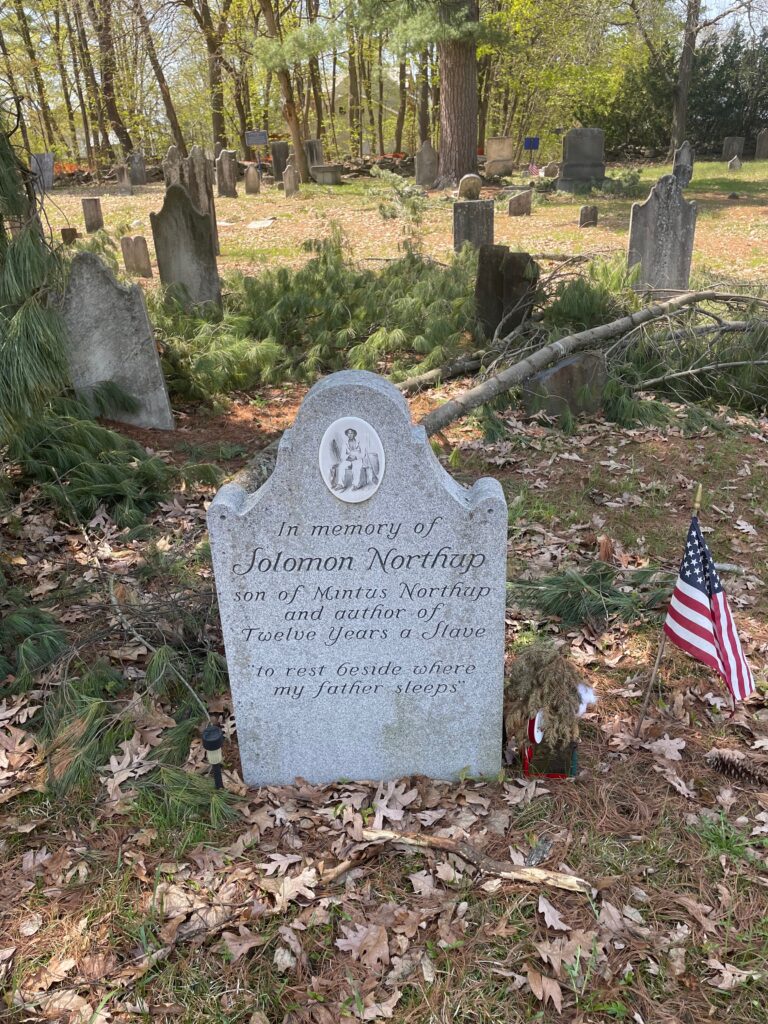

This is the possible grave of Solomon Northup.

Born sometime around 1807, Northup was born free, in Minerva, New York. This would be central to the horrors he experienced later in life. His parents were both free Black people. The family worked on various farms in Washington County, New York. He married in 1829, to another free Black woman. After moving around a good bit, the family ended up in Saratoga Springs.

Northup was both a farmer and a violinist. He was a good musician and thus was in demand. He also did manual labor, building canals and railroads and such. Basically whatever it took to survive. But his musical career began to take off for real and he got gigs playing during the summer at the high end hotels of Saratoga, which was already a resort for the New York elite.

In 1841, a couple of white men approached Northup to play a gig in New York and then in Washington. Unfortunately, he took them up on it. They were not musicians. They were part of the scumbag group in America that sought to lure free Black people into their clutches and kidnap them into slavery. Since no one in the South had any interest in exploring the veracity of these claims, this happened all the time. It was disturbingly common. Moreover, these whites suffered nothing for it, even when they were caught. The old myths about the slavetraders being somewhat disreputable in southern society have been demonstrated to be completely wrong by historians. They were leaders in southern society and involved throughout politics and business.

For the next twelve years, Northup lived a living hell. We know all of this because of his powerful slave narrative he wrote on amazingly being freed in 1853, Twelve Years a Slave. Northup experienced owners were who total monsters and owners who were slightly less monstrous. He was a tough man and beat the living shit out of one owner, using the whip on the white instead. He survived this, probably because the guy, for whom Northup was the first slave he bought, had tons of debt and the guy who had loaned him the money for the slave told him no, he couldn’t kill him.

Now, Northup got word to the North that he had been kidnapped almost immediately. He got someone to deliver a letter while he was in New Orleans waiting to be sold. But while his family now knew he was alive, they had no idea where he was and no one could really do anything about it. Again, it’s not like there was a national slave registry. So for the next twelve years, Northup experienced the worst life could provide. This was the era in which new varieties of extremely productive cotton came to market and so the owners had all the incentive to work the slaves nearly the point of death (or past it) in order to get every boll picked since it was probably impossible even for driven slaves to truly pick them all. He saw the rapes, the whippings, the torture. He experienced plenty of the whippings and torture too. The hell of this is literally unimaginable and to have known thirty years of freedom before your kidnapping must have made it all the worse.

In 1852, a carpenter named Samuel Bass, a white guy from Canada, came to Louisiana to do some work on the plantation where Northrup slaved away. They became friends and Northup, knowing he was risking his life to tell his story, decided to tell it. Bass took huge risks himself. Outraged at hearing the story of his new friend, he took it upon himself to break the Fugitive Slave Act and do whatever he could to tell Northrup’s story. Northup was able to write letters to several friends and give them the best directions possible to the plantation in the remote area where he was.

Now, New York had passed a law in 1840 that committed the state to active legal assistance to help any Black resident kidnapped into slavery. It still had to follow the law, but in this case, word got out pretty fast and the government of the state sought Northup’s freedom. His owner was furious to have his property taken away. The guy did not see what Northrup’s legally free status should matter at all. After all, at this time, Northup was his property. But with all the legal backing, there was nothing he could do about it. Northup was free.

Northup came home, got to know his family again, and rested to restore his broken and beaten body. In fact, he never would be healthy again. That was the point of slavery after all. Working with a local writer, Northup then spent the next two months writing Twelve Years a Slave. It sold well, about 30,000 copies. Northup then went on a lecture tour around the North in order to tell his story and make more money. He also tried to have the men who kidnapped him prosecuted and convicted, but while there was a trial in New York, the bastards never did see the inside of a cell. Who knows how many others they kidnapped over the years.

Then….Northup disappears from the public record. Some speculated he was even kidnapped back into slavery, but this is unlikely. There are at least some reports of him helping people on the Underground Railroad and meeting with local people into the 1860s. He probably died in 1864 and was probably around 57 years old.

As he died in unclear circumstances, Northup’s burial site is not authenticated. But this is also the site of his father’s grave, there’s plenty of speculation at least that Northrup is buried there too, and it’s as good of a guess as any. So it at least gave me the chance to tell his story in this series.

Solomon Northup is possibly buried in Baker Cemetery, Hudson Falls, New York.

If you would like this series to visit other survivors of slavery, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Blanche Bruce is in Washington, D.C., and Norris Wright Cuney is in Galveston, Texas. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.