Policy-Blogging: The History of Price Controls

Anonymous asked:

Do price controls work as a way to control inflation or do they normally make the problem worse by discouraging production, and thus supply? On the other side of the equation, does raising minimum wages help mitigate the effects of inflation or just encourage further price increases?

This is a great question!

The TLDR: they can work, but as with any other form of economic policy it depends on the state of the economy, how they are designed and enforced, and how they are coordinated with other economic policies.

The Theory

Most economists absolutely loathe price controls, because they believe controls prevent the operation of supply and demand from smoothly “clearing” the free market, and “distort” the “signals” that prices are supposed to send to businesses and investors, and so forth. At the same time, they argue that price controls lead to reduced supply and black markets, and thus are counter-productive. In this view, price controls are simultaneously too effective in their impact on the economy and completely ineffective in achieving their intended effect.

There is a kernel of truth to that – but only a kernel. I would argue that price controls are among the most difficult economic policies that a government can undertake:

- they require very careful design, because you need to identify the most significant goods and services that have to be controlled and how their prices affect the prices of other goods and services (parts and raw materials, utilities and transportation costs, wholesale versus retail, finance and credit), and you need to balance profitability versus prices, and most of all you have to balance capital and labor in order to get the right mix of investment and consumption.

- they require a lot of state capacity to administer and enforce. One major reason why history – especially early history from the Edict of Diocletian on down through medieval and early modern controls on grain and bread to prevent food riots – is littered with failed controls is that they require an enormous amount of bureaucratic labor to watch over producers and retailers to ensure that goods are being sold at the appropriate price, and a very high quality of expert labor when it comes to collecting and analyzing economic data to see if the controls are working and whether and how they need to be adjusted or reformed on the fly in order to maintain efficacy.

- they have to be coordinated with all aspects of economic policy, especially fiscal and monetary policy, because there’s a risk of counter-acting forces within the state. You don’t want a scenario where price controls are trying to keep prices down, but increased spending and loose monetary policy are pushing them up, or vice versa. In addition to the big two, you also want your financial regulatory agencies and labor law agencies pushing in the same direction as your controls, because they have significant influence on credit and labor markets. Moreover, good controls coordinate by bringing in stakeholders – you want to bring in business and industry groups to get buy-in, but you also need to bring in labor to counter-balance them and to get buy-in so that controls don’t lead to increased strike actions. One of the major difficulties of a lot of controls have run into is how to bring in consumers, because they tend to be under-organized (compared to business and labor) outside of (often small) consumer advocacy organizations.

That being said, there are some historical examples of price controls that worked, which I’m going to talk about in the next section.

The Other NRA

This one is my most contrarian and counter-intuitive example, because the NRA is usually held up by both the left and the right as a failure of price controls – the left views the NRA as a stitch-up by business interests that failed to enforce the right to organize, the right views it as a totalitarian infringement on the rights and liberties of kosher poultry conglomerates.

Famously, the first major historian of the New Deal, Arthur Schlesinger Jr., argued that FDR made a critical staffing error by placing the charismatic, fast-moving, and media-savvy but unstable Hugh S. Johnson in charge of the NRA even though Johnson didn’t believe that it was constitutional, and putting the cautious, detail-oriented, penny-pinching, and slow-moving Harold Ickes in charge of the Public Works Administration , even though his insistence on getting the best possible contracts slowed down the approval process to a crawl. Schlesinger argued that had FDR done the reverse, Ickes would have negotiated and enforced better price controls while Johnson would have gotten the money out the door faster.

Now, it is true that the NRA suffered from design and implementation problems. The NRA was supposed to operate by getting industrial committees made up of business, labor and consumers to negotiate industrial codes that set prices, wages, working conditions, and market shares in order to raise prices and counter-act deflation (following the overproduction thesis) and raise wages and thus consumption (following the underconsumption thesis). If you want to know more about this, I highly recommend Kathleen Donohue’s Freedom From Want.

In practice, business was much better organized and represented, while the labor provisions that were supposed to provide for a minimum wage and the right to organize were too weak to be properly enforced in the face of business opposition and the AFL was too standoffish and disengaged, while Florence Kelly’s National Consumers League was often ignored and overlooked in negotiations. The left-wing economists in the NRA were very, very good, but they weren’t staffed at the levels that they needed to be to oversee a program of this magnitude, nor were they given the authority to really put their theories into practice – and a lot of them were red-baited by industry and conservatives in government.

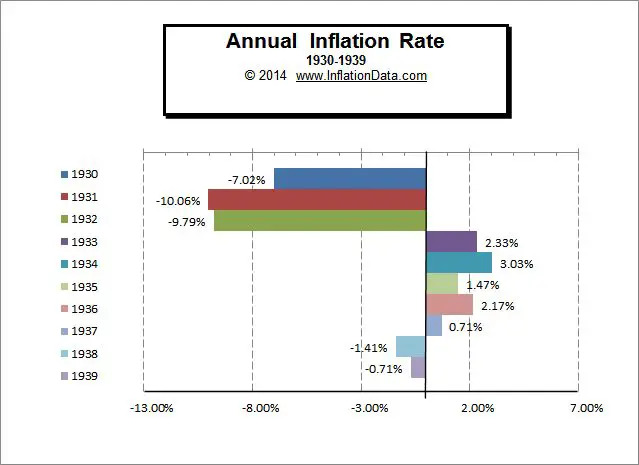

For all these faults, however, the NRA succeeded in accomplishing its mission of ending crippling deflation that had devastated American industry and producing modest levels of inflation between 1933 and 1935:

Nor did the NRA’s controls hold back economic recovery. GDP turned around from a negative 1.2% rate in 1933 to 10.8% growth in 1934 and 8.9% in 1935 – one of the fastest recovery rates in American history. Critically, workers shared in the recovery: hourly wages rose from 46.7 cents in January 1933 to 57 cents in January of 1935 – which works out to a 10% annual increase at a time when prices were only going up by 2-3%.

Economists can argue all they want that the economy would have been even better without the NRA, but we’ll never know for sure. What we can say is that the NRA was compatible with a robust recovery.

“General Max” – the Office of Price Administration

However, the best example of successful price controls is the wartime price controls during WWII operated by the OPA. The OPA was tasked with a seemingly impossible mission: keep prices down at a time when the Federal government is increasing spending to almost 50% of annual GDP and a newly-unionized workforce is experiencing the first truly full employment in American history and is working not just full-time but overtime, swelling their paychecks even further. If that wasn’t enough, the OPA also had to run a national rationing system.

As discussed by Meg Jacobs in Pocketbook Politics, which I also highly recommend, the OPA was a major improvement on the NRA:

- It was staffed by some of the best economists in the United States, from Leon Henderson to John Kenneth Galbraith to (ironically) Milton Friedman. Economists moreover were given real authority from the very top of the agency through to its policy, statistics, and research divisions.

- It was heavily resourced, especially with statisticians and researchers who became a major part of the statistical revolution that brought in our modern understanding of national accounts, allowing the U.S government to track both macro- and micro-economic data – GDP, GNP, the Consumer Price Index, and other measurements that we rely on to guide the economy today were invented then and there.

- It was well-coordinated with other branches of public policy, especially with the War Production Board, the National War Labor Board, and the War Finance Division of the Treasury Department. Thus, business was kept sweet with an enormous flood of government contracts, while labor was kept relatively peaceful with union recognition, pensions and insurance, and over-time pay, while huge bond drives sucked consumer dollars out of the wartime economy and into the post-war economy.

One particular strength of the OPA was its enforcement arm. To supplement government bureaucrats in Washington D.C, the OPA mobilized millions of housewives across the country into local advisory committees. As the primary household purchasers, these women were keenly aware of price changes at their local retailers – and now the government gave them real enforcement power by putting them in charge of monitoring compliance and initiating complaints of violations. Thus, OPA directives were enforced both at the macro- and micro-level.

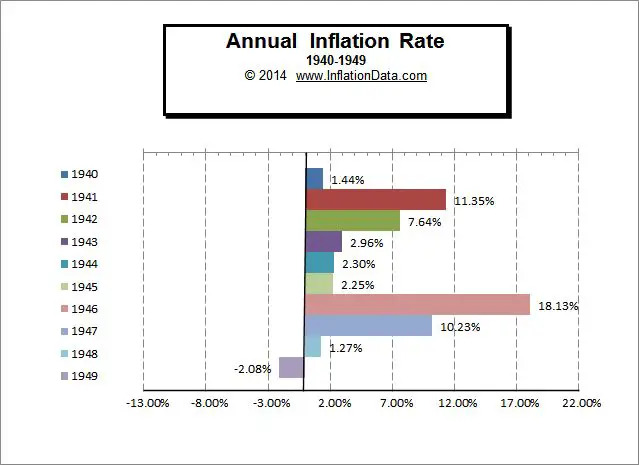

The results were astonishing. At a time of total economic mobilization, where production capacity was essentially 100% utilized, workers were essentially 100% employed at more than 100% time, and the economy was growing at 12% per year (the fastest on record), the OPA brought inflation down from 11% down to under 3%.

As a result, the OPA was enormously popular and was continued after the war. The problem was that business absolutely hated it and essentially conducted a capital strike in late 1945, pulling goods off the market especially in highly noticeable areas of the economy like meat and other food items. Between this move, intensive lobbying by the National Association of Manufactures and the National Retail Dry Good Association, and red-baiting by conservatives in Congress, the OPA was massively weakened and ultimately allowed to expire – with no help from Harry Truman, who badly mishandled negotiations with Congress in 1946 and 1947.

The result was skyrocketing inflation that was only curbed by the Federal Reserve clamping down on monetary policy and causing the recession of 1949.

Fuck Richard Nixon

To give an example of what price controls done wrong looks like, you can look no further than the price controls imposed by the Nixon Administration between 1971 and 1974. Originally intended to deal with inflation caused by LBJ’s “guns and butter” approach to Vietnam War spending and then pressed into service to deal with the Oil Crisis, these price controls were pretty systematically mismanaged.

As Meg Jacobs describes in her book and Judith Stein describes in Pivotal Decade, Nixon made a series of mistakes in how he approached controls that he had opposed throughout his political career. His first huge mistake was that he imposed wage controls first and then price controls after several months lag – this caused a significant decrease in real wages and permanently alienated the AFL-CIO, so that labor had no buy-in, leading to a massive strike wave (and preventing future price controls from being enacted during the Iranian oil crisis).

His second huge mistake was that Nixon initially exempted agricultural prices in order to maintain popularity in the farm states, which made the price controls ineffective in curbing inflation as food prices shot up through the roof, further reducing real wages.

Nixon’s third mistake was that his controls were also badly coordinated, as the wage and price controls were announced at the same time that Nixon was boosting Federal spending and loosening monetary policy to win re-election, and had just gone off the gold standard and ended the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, further destabilizing the situation. The result was massive uncertainty and instability, not helped by the fact that Nixon kept imposing, removing, and then re-imposing them, so that no one could predict the course of economic policy.

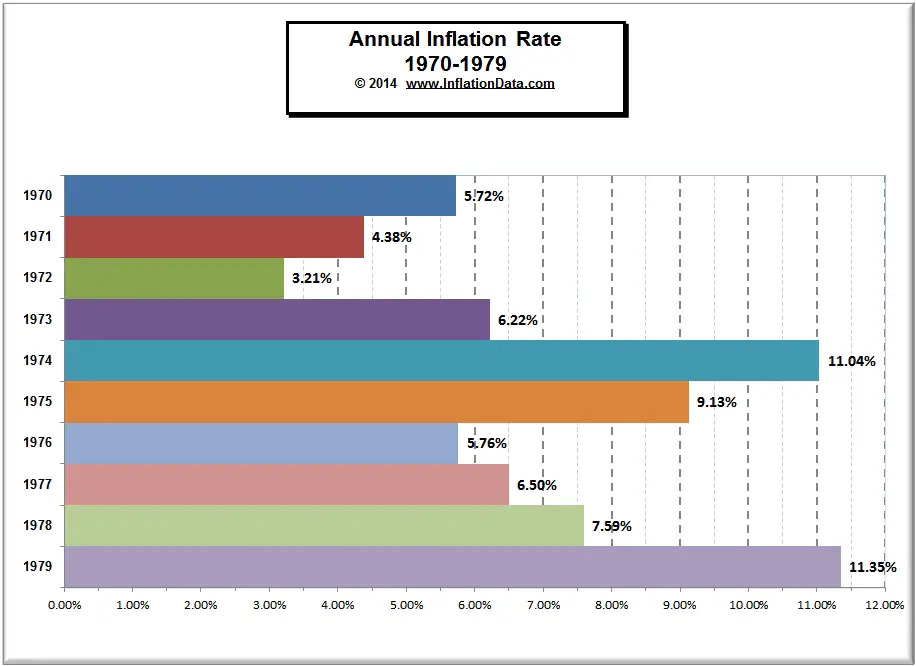

While Nixon’s price controls did modestly reduce inflation in 1971 and 1972, they completely collapsed in 1973 and 1974 in the face of the Oil Crisis. The result was stagflation – simultaneous economic recession and high inflation.

So yeah, never trust a conservative Republican to a job for a New Dealer.

Conclusion/Sidenote

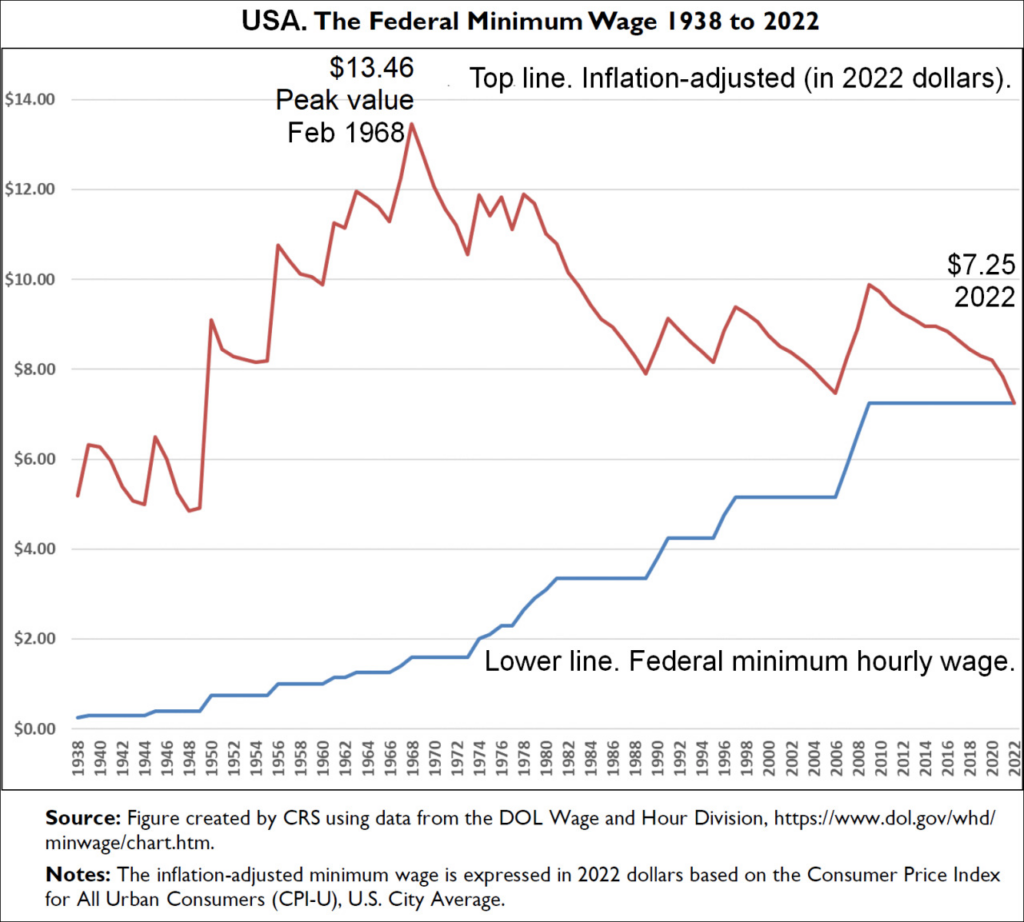

To answer your final question, which touches on work I’m doing for my next book, the Federal minimum wage is not currently designed to deal well with inflation. Because it is set in nominal rather than real dollars, the minimum wage does not automatically rise in step with inflation in the same way that Social Security usually does through COLAs (cost-of-living adjustments) and thus loses real value over time unless Congress intervenes to pass an increase.

In the 1970s, it was certainly alleged that the minimum wage encouraged inflation and harmed minority youth employment – although later research would largely disprove most of these studies from the 1970s – but the reality was that even with relatively frequent increases passed by Congress, the minimum wage was only able to “jog in place” significantly below its peak value in 1968.

And if you ever want to know more about an alternative method for fighting inflation while achieving progressive economic goals (hint hint), next time ask me about John H.G Pierson and the Macunian tradition.