Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,386

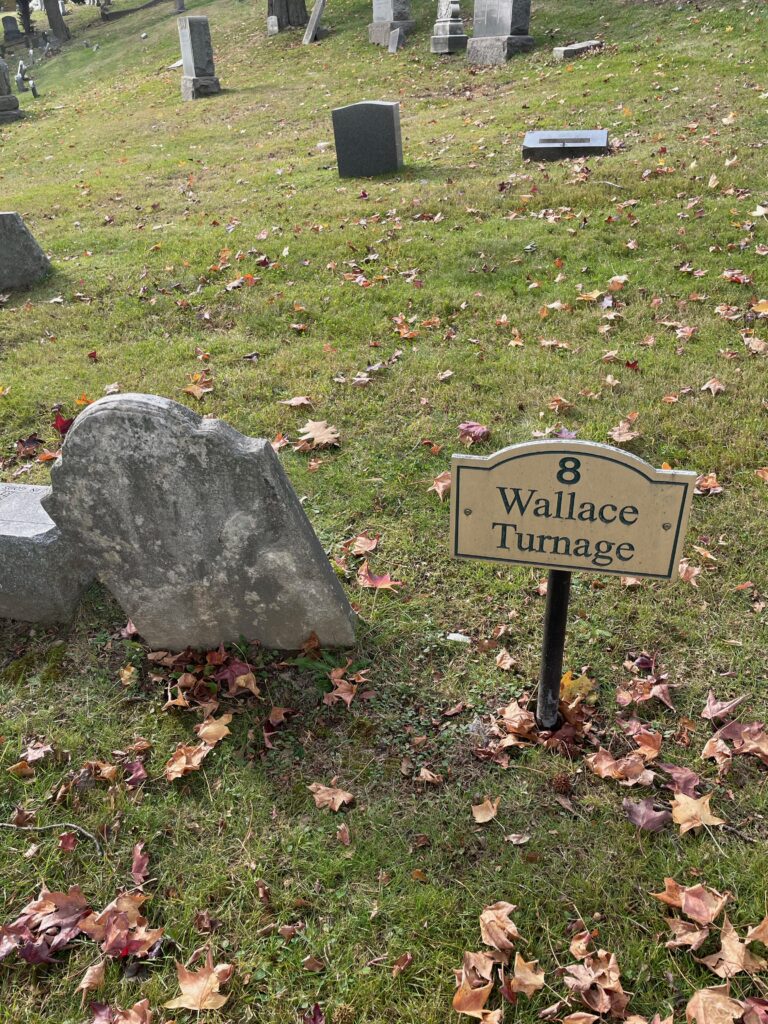

This is the grave of Wallace Turnage.

Born in 1846 in North Carolina, Turnage grew up in slavery. Like so many slaves, he was the product of rape. His mother was 15 years old when he was born. If anything, we still undersell the amount of sex slavery that existed in the South. He was first sold pretty young and over the years, experienced all sorts of brutality from the various owners he had. In 1860, he was sold to a cotton planter in western Alabama, near the Mississippi line. He was whipped almost immediately. He attempted to escape several times during his young years, five in total before he succeeded. He was owned by a merchant. The first four times, he was caught while traveling along a railroad, trying in some way to get back to his mother in North Carolina. One time, when he was caught, he fought back ferociously and nearly bit off a guy’s ear. For that, he was nearly whipped to death. Another time, the guy who caught him got drunk and threw him into an active fireplace.

In 1863, sick of this, Turnage’s master finally sold him and he ended up in Mobile, Alabama. There, Turnage finally successfully made his escape. Unlike New Orleans, Mobile was held by the Confederates until almost the end of the war, but it was still a mess by 1864 and white control of the slave population had diminished. But escape still wasn’t easy. In fact, his final escape started with another failed escape. He had tried to escape after an argument with his new master over a flipped carriage. He hid in the city for a week, got caught, was whipped 20 times, and then told to walk home. But despite pain that I cannot personally imagine, he did not walk home. He walked straight out of the city and somehow did not get caught. He walked about 25 miles, and hid in an estuary of the bay, trying to avoid alligators and snakes. Here, he managed to find enough to eat to stay alive and stayed in the estuary for about three weeks. He stumbled across a rowboat and took it, rowing to Fort Gaines and finding Union forces. This was quite the escape. He was taken in by quite sympathetic Union forces and became the cook for a Union officer. He marched with the Union army into Mobile in March 1865.

After the war, Turnage moved to New York. He did all sorts of thing for the rest of his life, trying to make a living. He worked as a janitor, as a waiter. He worked blowing glass. He later worked as a watchman. He wasn’t a rich man or particularly a great financial success. He was just a guy in the Black working class, which meant tremendous poverty. But he learned to read. And he learned to write. Before he died, Turnage decided to write down his experiences as a slave and the story of his escape. By this time, the age of the published slave narrative had mostly passed. Those slave narratives that we mostly know today--Frederick Douglass, Harriet Jacobs, etc.–were written before and during the Civil War and shaped to appeal to white middle and upper class women involved in reform politics. Their stories are definitely true, but they are also shaped for the market, just like any book and they have to be read that way. After the Civil War, interest in the stories of ex-slaves dropped out of the market. So when Turnage wrote his memoir, he gave it to his daughter for the future. He wanted his family to know, if no one else. The memoir is powerful. Of his time in the swamp, when death was around every corner, he wrote, “It was death to go back and it was death to stay there and freedom was before me; it could only be death to go forward if I was caught and freedom if I escaped.”

The manuscript passed down through Turnage’s family through the generations. Finally, it was discovered by the great historian of Civil War memory, David Blight. If you haven’t read Blight’s books, you need to get on that like yesterday. Blight was amazed by this text and another he had found by an ex-slave named John Washington. So he edited them, wrote an introduction, and got them published as A Slave No More: Two Men Who Escaped to Freedom, Including Their Own Narratives of Emancipation, in 2007.

Turnage died in New York in 1916. He was approximately 70 years old.

Wallace Turnage is buried in Cypress Hills Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York.

Not many of the people who wrote slave narratives have known graves and I’ve visited a lot of them. But if you want this series to visit other contributors to the Black literary tradition, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Zora Neale Hurston is in Fort Pierce, Florida and Octavia Butler is in Altadena, California. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.