Asteroid City

I watched Wes Anderson’s latest, Asteroid City, on Wednesday, and came away thinking that it was delightful but slight. The further I get from the movie, however, the more it lingers in my mind, and the greater its impression becomes. This is not just a funny movie—though it is funny, perhaps the most laugh-out-loud thing Anderson has made since The Grand Budapest Hotel—but a joyful one. And that joy persists despite, or perhaps because it is, like so many Anderson movies, fundamentally about loss and disillusionment. In some ways it feels to me like the most complete, most mature handling of that duality in Anderson’s filmography.

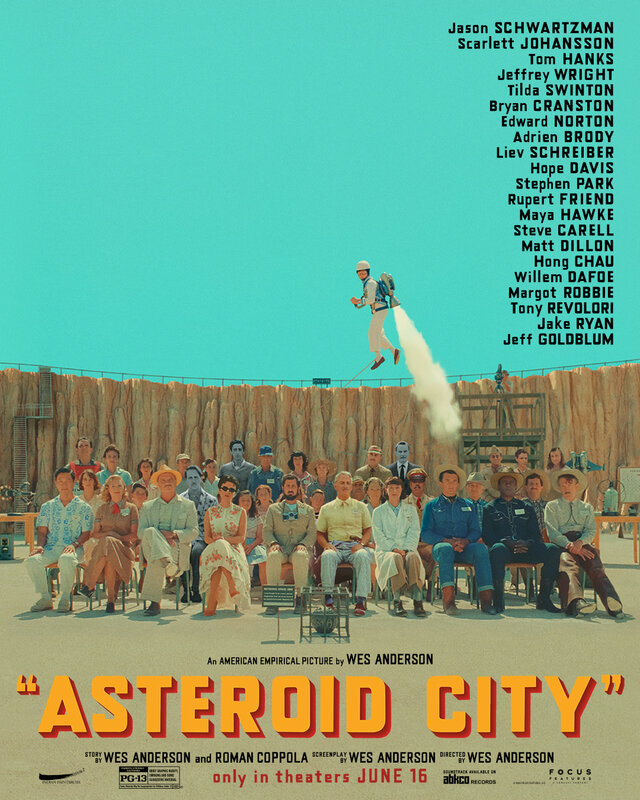

Asteroid City is a wide space in the desert road in 1955, site of a long-ago meteor crash and not much else. As the film opens, the town is playing host to a Junior Stargazers convention, in which young teenage eggheads show off inventions like a working jetpack or death ray, and discoveries such as new elements, while their harried parents look on with as much impatience as pride, and wonder where the nearest alcoholic beverage can be procured. At the end of the first act, an unexpected event places the town under quarantine, forcing both parents and children into new relationship configurations.

Parent-child relationships have been at the heart of many of Anderson’s movies: the fracturing mentorship of Rushmore, the tentative meeting between an adult child and his unwitting father in The Life Aquatic, the absent and deceased parents in The Darjeeling Limited. And, of course, in The Royal Tenenbaums, which to many people seems to be the ur-Anderson work, but which I’ve always found a little too mannered and self-important. Asteroid City feels to me like a better handling of similar “drama of the gifted child” material, in part because it approaches it from the perspective of the parents.

Our main characters are Augie Steenbeck (Jason Schwartzman), a recently-widowed war photographer who is accompanying his son Woodrow (Jake Ryan), and Midge Campbell (Scarlett Johansson), a movie star chaperoning her daughter Dinah (Grace Edwards). But there are, in addition, a wide cast of characters—including but not limited to Liev Schrieber, Hope Davis, Stephen Park, and Maya Hawke—whom the camera tracks across just as it tracks across Asteroid City’s elaborate, toy-like set, dipping in and out of their conversations. And what these characters talk about, mostly, are their children—boasting about their accomplishments, grousing about their demands, worrying about their future.

It’s a familiar theme—the young are full of promise and possibility, while the middle aged remind us how often that promise remains unfulfilled, or is simply watered down by life’s demands and compromises. The fact that Schwartzman had his big break playing just the sort of boy genius that his character in Asteroid City is now parenting only drives this point home, as does the film’s SFnal premise and mid-century setting. Science fiction—especially the kind that was being written in the 1950s—is the literature of possibility, but as people watching in 2023, we know how few of the dreams of space exploration and alien encounters that the film’s young characters take for granted actually came true.

What’s special about how Asteroid City handles this theme—what makes it, as I said, joyful rather than tragic—is that it doesn’t forget that its parent characters are also people in the midst of their own lives, and that those lives, despite their complexity, despite carrying behind them a weight of disappointment and loss and bad decisions, are still exciting and vibrant in their own right. Augie and Midge both worry that they are too wrapped up in their own careers to be good parents, and Augie, of course, is bowed down by the responsibility of parenting Woodrow and his young daughters alone. But while these concerns are probably warranted—Augie briefly considers leaving his children with their grandfather (Tom Hanks)—the film doesn’t treat this as a sin or a failure. It respects the fact that these people still have their own lives to live, and reinforces it by reminding us that the children are doing the same—they have their own storylines, their own burgeoning relationships, their own plans for the future, which are no less significant because they’re happening to young people. Sometimes the parents need to play a part in these dramas—Schrieber, whose son (Aristou Meehan) has been daring himself to do increasingly ridiculous and dangerous things, finally breaks down and asks what that’s about, and when he learns that the kid is just looking or attention, gives it to him. And sometimes they need to step back and let their kids be people, as Park does when his son (Ethan Josh Lee), who has leaked news of the quarantine to his school paper, insists to the military that he will “fight [them] all the way to the Supreme Court and win!”

The framing story of Asteroid City is that the whole thing is a play whose production is being filmed for television (actually, that the play has been invented for a television production about putting on a play; it gets pretty heady). Here, too, the idea of parenting rears its head—the director (Adrien Brody) and his soon-to-be ex-wife (Hong Chau) share a moment of contentedness admiring their son’s report card. But the significance of it seems, to me, to be in the fact that we all sometimes feel like we’re playing a part. That even as adults who may be parents themselves, we still feel like we’re faking it, and maybe getting it all wrong. The central event of Asteroid City is one that shakes the adults just as much as the children, that leaves them wondering whether they really understand the world, but also remembering that they are not beyond wonder and new experiences. Stunned by this revelation, Augie—or rather, the actor playing Augie—walks off stage and nervously, heartbreakingly questions everyone in the theater: “am I doing it right?”

Unlike the Salinger-esque Royal Tenenbaums, which was so wrapped up in the tragedy of growing up, Asteroid City is able to recognize that the disappointments of adulthood are fine, even good in some ways. “You’re shy, but you’ll grow out of it,” is Augie’s repeated refrain to his son. But Augie himself, and Midge and even Hanks’s character, are all still growing themselves, still finding new ways to be people while their children find their own place in the world. There’s something beautiful about Asteroid City‘s depiction of this that means that, despite the sadness of its subject matter, I can’t think back on it without smiling.