The greatest threat to the Supreme Court’s legitimacy is the naked partisanship of the Republican justices

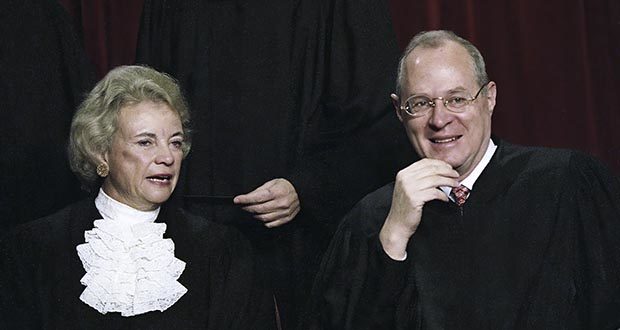

A tranche of John Paul Stevens’s personal records have been released, and they remind us what a lawless atrocity Bush v. Gore was. Sandra Day O’Connor took the lead in ensuring her preferred candidate would win after having expressed dismay when the election was called for Gore that she would be prevented from retiring:

O’Connor laid the groundwork for that result in her December 10 memo to all her colleagues as she condemned a Florida state Supreme Court decision ordering selective recounts of “undervotes” in certain counties.

She opened by highlighting state legislative authority to set the rules for the appointment of state presidential electors but quickly focused on the flaws, as she perceived them, of the ongoing recounts ordered by the state court.

“The Florida Supreme Court provided no uniform, statewide method for identifying and separating the undervotes,” O’Connor wrote, referring to instances when machines had failed to detect a vote for president. “Accordingly, there was no guarantee that those ballots deemed undervotes had not been previously tabulated. More importantly, the court failed to provide any standard more specific than the ‘intent of the voter’ standard to govern this statewide undervote recount. Therefore, each individual county was left to devise its own standards.”

The reason that the Florida Supreme Court did not mandate a uniform recount standard is because the Supreme Court of the United States had warned it not to. And the “intent of the voter” standard was the standard that was established doctrine in the Florida courts, and was applied consistently in this case although in a majority of lawsuits this favored Bush.

As Kim Scheppele observed about this Catch-22:

What is wrong with this, on a rule-of-law account? A great deal, but let me concentrate on two things in particular:

(1) The Whipsawing Problem: There was an apparent shift in the legal frameworks that were found to be important as one case followed another, leading to a sense that the applicable law was not stable and making it very difficult for anyone to orient their conduct in light of the law either before, during, or after the sequence of litigation.

(2) The Impossibility Problem: There was, in the per curiam opinion in Bush v. Gore, an announcement of two crucial legal conclusions-that an equal protection test applied to court-ordered vote-counting procedures and that 3 U.S.C. § 5 combined with a “legislative wish” required that recounts not be extended past the December 12 “safe harbor” date. But these two conclusions worked at cross-purposes. Meeting one required violating the other, and vice versa. With this logic, there was simply no place left to stand to claim a remedy that the law seemed to allow and perhaps even to require. The election was declared over as it stood at the moment the Court issued its decision, and no state has ascertained whether the results as they stood on the evening of December 12, 2000 met the equal protection standards the court laid down.

From all of this, we might legitimately wonder whether the United States in fact decided its most recent presidential election according to any coherent law at all.

Catch-22s are not consistent with the rule of law. O’Connor wanted Bush to president, and concocted a ridiculous “heads I win, tails you lose” sequence of opinions guaranteeing this result irrespective of the law or the facts. And the amazing thing is that the nutty independent state legislature reasoning being offered by Rehnquist was even worse!

This led to Alito-avant-la-lettre complaints that the threat to the Court’s legitimacy wasn’t the Court acting in a transparently indefensible matter but people pointing out that its conduct was indefensible:

“Going home after a long day,” Scalia wrote to fellow justices when it was all over on December 12, “I cannot help but observe that those of my colleagues who were protesting so vigorously that the Court’s judgment today will do it irreparable harm have spared no pains – in a veritable blizzard of separate dissents – to assist that result. Even to the point of footnote 4 in Ruth’s offering (I call it the Al Sharpton footnote), alleging on the basis of press reports ‘obstacles to voting disproportionately encountered by black voters.’”

Well-known for his take-no-prisoners dissenting views, Scalia added, “I am the last person to complain that dissents should not be thorough and hard-hitting (though it would be nice to have them somewhat consolidated). But before vigorously dissenting (or, come to think of it, at any other time) I have never urged the majority of my colleagues to alter their honest view of the case because of the potential ‘damage to the Court.’ I just thought I would observe the incongruity. Good night.” He signed it, “Sincerely, Nino.”

In their opinions, liberal dissenters had emphasized the cost to the court as an institution and, in Breyer’s words, “damage” to the country.

Similarly, Kennedy wrote to colleagues that same day, “I do not usually respond to dissenting opinions, and will not do so for the per curiam in this case. I take the occasion in this memo, however, to say that the tone of the dissents is disturbing both on an institutional and personal level. I have agonized over this and made my best judgment. Some of the dissenters in fact agree on the equal protection point, but take great pains to conceal that agreement. The dissents, permit me to say, in effect try to coerce the majority by trashing the Court themselves, thereby making their dire, and I think unjustified, predictions a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

The fact that Ginsburg responded to Scalia’s racist characterization of her indisputably correct point by allowing herself into being bullied into removing the footnote is what we might call foreshadowing. Another reason the Court has become illegitimate is the belief of certain liberal elites that they have an obligation to be part of the cover-up.