Post-Dobbs Politics

Rebecca Traister has a good dive into the political impact of the Supreme Court’s abrogation of five decades of reproductive freedom. The impact of a mobilized and expanding pro-choice majority is being felt in some critical swing jurisdictions, especially when abortion is on the ballot:

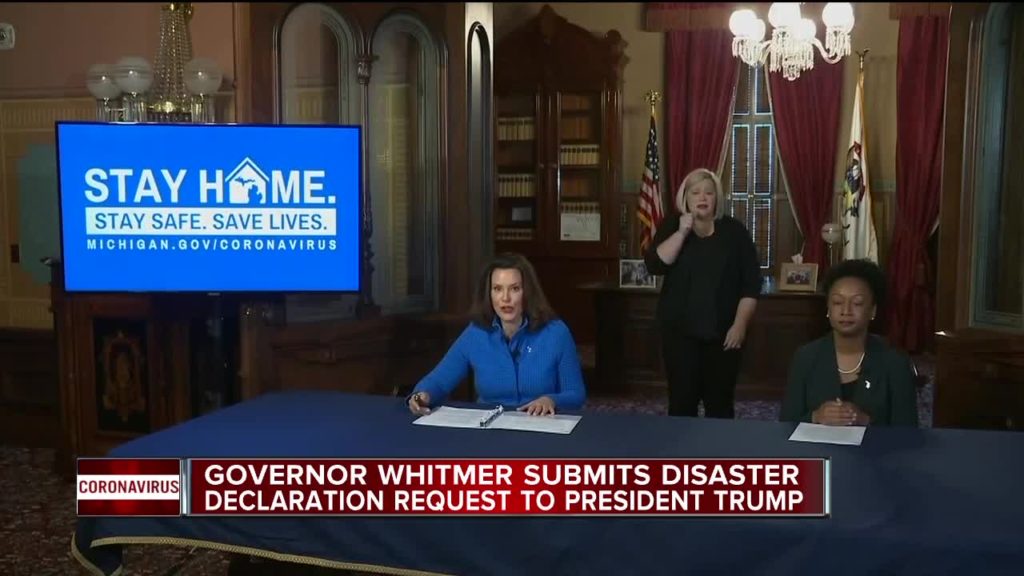

At the state level, the face of a new approach to abortion politics is indisputably Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer. “If you look at what happened across the country, there was no more profound outcome than in the state of Michigan,” Whitmer told me two days before her State of the State address in January. “We won all the constitutional offices; we flipped both chambers of our legislature for the first time in 40 years. It’s only happened four times in 130 years in the state.”

Democrats’ success was owed in large part to the presence on the ballot of Prop 3, a citizen-driven constitutional amendment that protected abortion rights in the state. Whitmer and her fellow Michigan Democrats were unique in that they had been running on abortion before Dobbs and continued to do so even when, in the months before the November elections, Democratic leaders and strategists cautioned them to ratchet it down a notch. Their gamble paid off: According to Bonier, the gender gap in Michigan in favor of Democrats was even higher than it had been in 2018, when it had hit a historic peak. And Whitmer — or “Big Gretch,” as she was appreciatively nicknamed by Detroit rapper Gmac Cash in 2020 — was at the forefront of channeling that raw support into an agenda. “I was so associated with the issue I don’t know how you pull it apart” from other aspects of the platform, she said.

Big Gretch, 51, has Ava Gardner bone structure, a flat midwestern cadence, and a fondness for athletic metaphor (before politics, she had planned to go into sports broadcasting). She is widely referred to as a possible future presidential contender. And she is selling abortion as both a practical, voter-friendly issue and an inalienable human right at the center of a galaxy of related concerns.

At the Michigan State of the State, she did not treat abortion as Democrats often do, as if it’s slightly icky and private, damp and sad. She did not cordon it off in its own dolorous corner separate from all the rousing stuff about creating a mighty Michigan economy. Rather, she led with it, weaving it into a business-forward spiel called “Make It in Michigan,” suggesting that prioritizing abortion rights and LGBTQ+ protections would help bring businesses and expertise back to her former manufacturing state. States with anti-abortion and anti-trans laws, she told her audience, “are losing talent and investment because bigotry is bad for business.” Then she went ahead and cast these issues as universal family values. “Every parent,” Whitmer said, “Republican, Democrat, or independent, wants our kids to stay in Michigan. Let’s give them reasons to stay; let’s … protect fundamental freedoms.”

In most jurisdictions, there’s no need to be apologetic or defensive — the public is with Democrats on this and they need to push hard.

Needless to say, these remedies are no available in every state, which is one reason why Rucho was a necessary predicate to Dobbs. And why one has to hope that reproductive freedom will help win the upcoming judicial election in Wisconsin.