“Everybody’s at war these days, let’s have a mini-surrender:” Warren Zevon’s Sentimental Hygiene Turns 35

Sometimes, when I can’t face my deadlines, I have this conversation with myself:

“Hey Beth, that review/feature/cultural meditation isn’t going to write itself. Every minute that ticks by is one more minute where you elect to marinate in decadent mediocrity. How many times have you checked today to see if *non-vital player* on your fantasy football team is expected to be active on Sunday? Six? Is that characteristic of a high functioning mind?.”

This is how I upbraid myself for procrastination. Interestingly, what often follows from that low-bottom is the following thought: Hey, I haven’t done one of those things for a while where I talk about a whole album on LG&M! Let’s do that!!

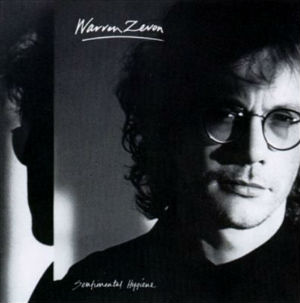

Let’s. And let’s make this particular act of delinquency LG&M brand-specific. Let’s do a retrospective on Warren Zevon’s enduringly wonderful, 1987 sorta-comeback, candy-aspirin landmark Sentimental Hygiene.

Sentimental Hygiene is a hard-nosed record, made by a man forged in the furnace of countless debased and traumatic experiences, though he’s not exactly sure what those experiences were. He has some memory problems. But the ambient gist remains: there were street fights and seizures, arguments with the fairer sex about esoteric questions of fidelity, some foreign travel and shifty accounting. Yes, substances were involved, if you have to know. A noted fan of genre fiction, Zevon is well and fully his own noir character by 1987, some broken musician who might have crawled out of the sleazier pages of a Ross Thomas novel. He’s a forerunner to the wise and mercurial drifter Bob Dylan has manifested in his mischievous and moving dotage.

By 1987, Zevon was forty (40!) years old and newly sober, but he’d gotten a lot of destructive work done in the several years previous. Music industry consensus had him pegged as a genius, but one so temperamental, erratic and aesthetically asymmetric that the juice would never be worth the squeeze. He had written countless transporting songs, but few hits. He was a reliably intoxicating live performer, but everything that happened off-stage was a sucker’s bet. You had to clear a pretty high bar for debauchery to be written off by the music business in the 1970s. Zevon soared.

Was this his last chance? Who knows, but for the sake of this article let’s say it absolutely was. How would he commercially rebound? How would he pull this off? As much as Zevon had spent the past decade alienating his cohort, he had been simultaneously burnishing his reputation amongst the self-styled fuck-ups of the American indie scene, which resulted in his dragooning burgeoning legends R.E.M. into being his backing band for Sentimental Hygiene. A two-middle-fingers-raised middle aged man recruiting a young group with anger management problems of their own. Perfect. R.E.M.’s thumping backbeat was just the Beatles-in-Hamburg kick in the ass that Zevon’s music always required but could never quite locate in the pacific weirdness of LA’s soft-rock scene.

He wasn’t weird like that — LA weird — but some part of him was enticed. He wanted to try on the hippie-Boomer dream. He wanted it to fit the same way it fit his gorgeous, unctuous friend Glenn Frey. But, if the Eagles have taught us anything, you can’t fake your way through Hollywood with any semblance of authenticity. Zevon could not comfortably exist in that male-narcissist utopia, though Zevon did exist in it uncomfortably and excessively for as long as it would have him. He could not make mainstream radio hits, because mainstream radio was wary about songs where beheaded ghost mercenaries stalk the world, indiscriminately seeking victims. He was stuck between stations, underground or overground, a horse with no sense prowling the LA desert. He was both Quixote and Sancho Panza. He made many a fierce charge, but the windmills always won.

Let’s go through Sentimental Hygiene track by track and conclude if we are any the wiser for it.

Sentimental Hygiene

A mid-tempo rocker which arrives like a question mark and departs after five furious minutes as an exhausting exercise in tireless groove, the title track sets the terms for the bare-knuckles fight to follow. The first words are these:

Every day I get up in the morning and go to work

And do my job, whatever

A perfect start and a get-wise memo to anyone who imagined Sentimental Hygiene would be a crowd pleasing mea-culpa by a man just happy to be back in the game. The “whatever,” of course, does the heavy lifting. In two lines Zevon has managed to annihilate two of popular music’s most aggravating tropes: that to sing songs to the world is a majestic gift, and that there is nothing like the simple pleasures of being a work-a-day-Joe. Whatever.

“I need some sentimental hygiene,” he sings with as much urgency but less persuasiveness then Marvin Gaye when the latter said the same about sexual healing. Weird synths chime in here and there as the band thunders on. A normal person would turn this album off. One of his best songs.

Boom Boom Mancini

Followed by an even better one. It is likely that Zevon saw a lot of himself in Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini, a popular champion in the lightweight division during the 1980s, when boxing was still adjacent to the center of sports culture and a thriving staple of network television. Mancini was humble, good-looking and fought with a pleasingly aggressive style. He was from Youngstown, Ohio where American’s used to make things but were being bled by the early throes of the post-industrial economy. He was only 20 when he fought ferociously but finally got his ass kicked in a title fight by the great Nicaraguan champion Alexis Arguello. Soon after he won a different version of the same 135-pound weight class title by knocking out Arturo Frias in the first round. He was electric. Boxing was still a subterranean game. So many marginal people thought they were going to get rich.

It took a year before things turned tragic. On ABC, in the afternoon on Saturday, Mancini made a mandatory title defense against the Korean Duk-Koo Kim. Back in the prehistoric days when footage didn’t travel the world like mercury, little was known of Kim. Mancini and his managers imagined he would be easily set aside in the pursuit of more lucrative matchups with Aaron Pryor, Roberto Duran or even Sugar Ray Leonard. This is not what occurred. Per a Men’s Journal lookback at the contest:

Kim’s style, it turned out, was a mirror of Mancini’s. He proved adept at phone booth warfare, fighting effectively inside and rarely taking a step back. As the fight progressed, it seemed only too possible that Mancini would suffer a shocking upset. As the rounds wore on and the toll mounted, Mancini later admitted he had thought of quitting.

When Duk-Koo Kim died of brain injuries following a 14th round knockout, it’s not like Mancini felt much better. He too had been battered to the point of senselessness. It’s there on YouTube. Don’t go watch it. Zevon-as-Mancini is indignant in the song, a hysterical rear-guard move to prove the ending was no one’s fault:

“When they asked him who was responsible

For the death of Duk-Koo Kim

He said, ‘Someone should have stopped the fight

And told me it was him.’”

Also:

“They made hypocrite judgments/ After the fact/ But the name of the game/ is be hit and hit back.”

This is one of Zevon’s best songs about his own persecution complex, whether he knows it or doesn’t. No one blamed Mancini, except maybe himself. He was never the same, defended his title two more times, got beat up badly a couple times and eventually drifted into obscurity. The “boxing commissions” and “sanctioning bodies” (aka unknowable, quasi-underworld cartels) eliminated fifteen round fights shortly thereafter on the theory that twelve round fights were less likely to turn lethal, which may be true, but nevertheless elides the greater truism that boxing is pure and simple a blood sport — hundreds of mini-human sacrifices in three minute increments. This is how Zevon views the music business as well. Anyone harmed by their association to him was just caught in the inevitable crossfire. The groove on “Boom Boom Mancini” is unstoppable.

The Factory

Continuing the meta-theme of labor and ambivalence which courses through Sentimental Hygiene like a muttered curse, “The Factory” as a lilting little first person narrative all about the deprivations and human toll of dead end work. It’s a good song, but because it is a Zevon song, you have to wonder exactly how seriously he is taking any of it. There is a smirk to his delivery, maybe more than a smirk. He might be completely bullshitting us – sending up his friend Bruce Springsteen or the more strident work of The Clash or Billy Joel’s “Allentown” or all of the above. I mean seriously – “The Factory?” Does Zevon even actually know what one is? Something with machines and no pianos? However earnest, or not his intentions, he can’t stop himself from making light of the situation.

I’ve been working in the factory

Johnny, I’ve been working in the factory

Kickin’ asbestos in the factory

Punchin’ out Chryslers in the factory

Breathin’ that plastic in the factory

Makin’ polyvinyl chloride in the factory

Polyvinyl chloride, he says. You know, what they use to make records.

Trouble Waiting To Happen

Buttressed by a customarily terrific Pete Buck riff and some great piano playing by Zevon “Trouble Waiting To Happen” is a doomsday confection which could have been a hit in some bizarro universe where men sing cheerful-sounding songs that anticipate WWIII and WWIV in the same couplet. He doesn’t sound overly vexed about the end of the world (in fact he sounds fine!) For the second time in four songs we start out with Zevon in bed, waking up, taking stock of the situation and feeling bemused and underwhelmed. The best gag, like all of his best gags, comes at his own expense.

The mailman brought me the Rolling Stone

Trouble waiting to happen

It said I was living at home alone

Trouble waiting to happen

Reconsider Me

A classic sandbagger, one of Zevon’s great tricks is to lull you into a sense of benignly low stakes, garden-variety clowning and bellyaching and recrimination only to detonate an emotional nuclear device in the middle of the proceedings just to see all of the faces melting around him. So it is with the side A closer, which wafts in on a weird bed of synths and distorted guitars and proceeds to relitigate everything in his wretched, reckless life in three minutes that evokes Sinatra’s In the Wee Small Hours by way of late-period Genesis. It is hard to say what it is about “Reconsider Me” that immediately reduces me to emotional rubble, but I know it has to do with the earnestness, which is so palpable and in such opposition to his typical posture of eye-rolling cantankerousness. The song’s looming subtext: can a person change? Can he? And by the way, is he even a person after everything he’s done? When you disconnect from your humanity, when you transgress against everyone that loved you, when you become so defiled your own mother wouldn’t recognize you – what comes next? If you’re Warren Zevon, you ask for a date.

And how beautiful and life affirming is that? This tremulous, strange, quavering ballad is one of his best songs for the very reason that it dares to explore the outer edges of forgiveness and redemption in radical- almost biblical- ways. And sure, he’s an inveterate shill and a conman and a backslider. Nobody’s perfect.

Detox Mansion

Having put a pin on his finest side of music in years, and indeed one of the best of the decade, Zevon returns to satirical, wise-ass mode on “Detox Mansion,” whose snaking guitar pulses and hard edged riffing draws heavily from R.E.M.’s Document. This is Zevon making fun of his own sobriety, and Liza Minnelli’s, who maybe he was in rehab with or maybe it’s just his imagination.

Well, I’m gone to Detox Mansion

Way down on Last Breath Farm

I’ve been rakin’ leaves with Liza

Me and Liz clean up the yard

Hot dog!

Anyway, it’s a ridiculous song, which is not to say it’s untrue. Especially when he sings: ”It’s tough to be somebody.” And how.

Bad Karma

Another classic. With its nagging two chord riff and infectious, Stonesy progression, “Bad Karma” is a clinic in songwriting craft, and an existential lament worthy of Samuel Beckett. This is the kind of stuff that he can do at his best which separates him from his peers. Zevon being Zevon, it’s a song about being cursed by birth to an exhausting life of Sisyphean-misery and it’s tremendous fun.

Was it something I did in another life?

I try and try but nothing comes out right for me

Bad karma, killing me by degree

This is how he starts out, clearly tickled by the proposition. And so it goes for three cheerful verses and a bridge: wrong turns on the astral plane, low-down-dirty shame after shame, early admission into the “all time losers Hall of Fame.” The band chirps along beautifully, with force and whimsy, in on the joke. Zevon has rarely sounded happier. But the punchline is: it isn’t a joke after all.

Even A Dog Can Shake Hands

Let the bad times roll! A delightful rave up which finds R.E.M. pushing Zevon to the outer limits of his comfort zone in terms of tempo, “Even A Dog Can Shake Hands” is a musical cousin to “Poor, Poor Pitiful” me and is the sort of thing that makes you wish he’d thrown in and made a full-fledged This Year’s Model at some juncture. The lyrics are a pretty funny satire of showbiz liars and crooked lawyers and other factotums of the music industry – it’s more of a glancing blow then a direct shot to the chin. But anyone who doesn’t enjoy hearing a rejuvenated Zevon whooping and hollering along with one of the great backing groups ever is everyone who never had a heart. Few songs in his catalog elicit such an easy smile.

The Heartache

Another beautifully rendered ballad which suffers only so slightly by comparison to the transcendent “Reconsider Me,” “The Heartache” is a cold-eyed look at love as a risk-reward proposition – a genuine wager and a dangerous one at that. Baring no small musical resemblance to some of Springsteen’s piano ballads – and without a doubt the influence with those two runs both ways – Zevon sings:

Shadows falling in the noonday sun

Blue feeling to the maximum

Look what happens when you love someone

And they don’t love you

Having been through personal apocalypses of his own making and lived to joke about it, this finally is the sum total of his wisdom. You may ask for forgiveness in the most florid of terms. If you are Warren Zevon, you may possess powers of persuasion well beyond your average mortal. But none of it will protect you if you make your case and the verdict goes sideways: if you’ve been reconsidered and the answer’s still no.

Leave My Monkey Alone

Zevon could’ve elected to leave his robust comeback album on the grace note of “The Heartache,” but that would have been insufficiently perverse. Instead we get this: a truly strange and inspired synth-pop song about colonial violence and bourgeois indolence which wouldn’t have sounded out of place on Leonard Cohen’s crypt-keeper disco extravaganza I’m Your Man. Zevon sounds confident back in Graham Greene international man of intrigue mode – as he does throughout this extraordinary record. Zevon would continue to put out great music for the rest of his days, a not insignificant achievement for a man who seemed assured to render himself asunder during his wilderness years. Alongside LPs like Time Out Of Mind and Some Girls, Sentimental Hygiene is an entry into the esoteric micro-genre of didn’t-see-that-coming renaissances. In 1987, a battle-scarred Warren Zevon stepped into the middle of the ring and saved his career. And maybe, if you want to be sentimental about it, he saved himself too.