Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,227

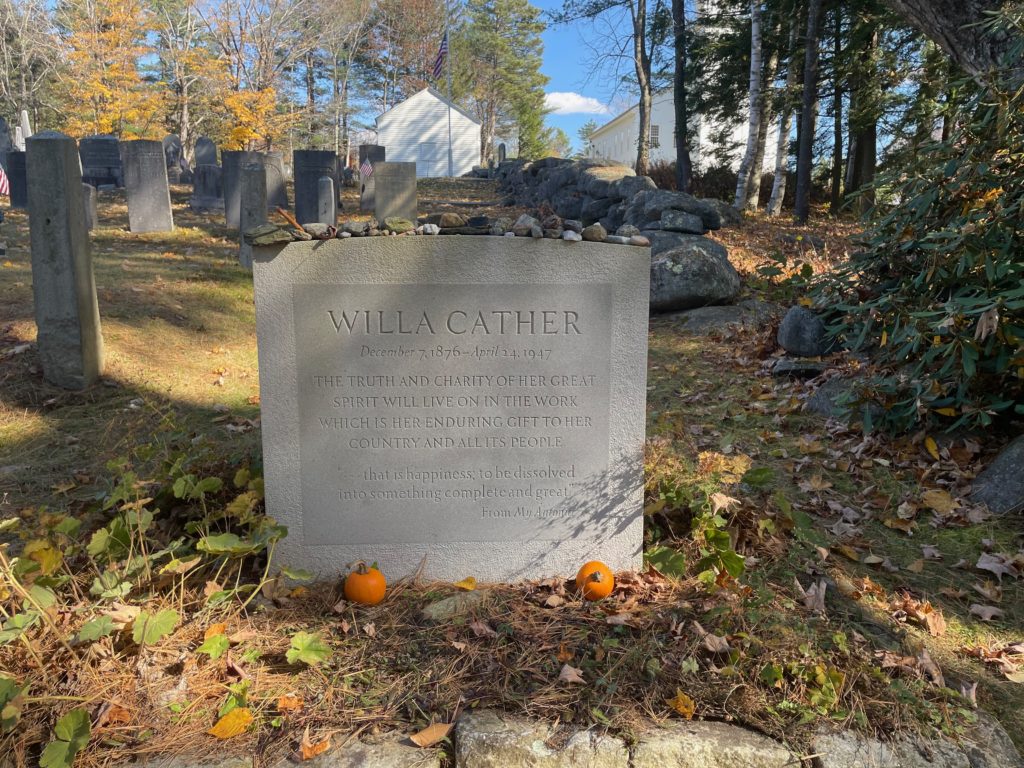

This is the grave of Willa Cather.

Born in 1873 in Gore, Virginia, Cather grew up pretty well off. Not knowing too much about her life really, I assumed she really did come from Nebraska settlers, but in fact she spent her first ten years in a big Greek Revival house on 130 acres of prime Virginia land that was her grandparents’ gift to her parents. But in 1883, the family decided to move to Nebraska for two reasons. First, her father had the farming fetish of Americans–the idea that tilling the land was the proper action for a man doesn’t quite have the power it once did in American life, but it was quite strong in the 1880s. Second, her father, who was a doctor by training, wanted to live in a drier country because he feared tuberculosis.

The farming thing didn’t work out at all because it hardly ever does. So after eighteen months of that, they moved to the town of Red Cloud and that’s where Cather finished growing up. Her father went into real estate and insurance and just lived the middle class life he always had. Willa was already somewhat experimenting with her gender identity by this time. She started writing for local papers and sometimes signer her name as “William” before settling on “Willa”–given that her birth name was Wilella, one can see why she might want to adjust that anyway.

Cather graduated from high school at age 16 and then went to the University of Nebraska. Initially she wanted to become a doctor and actually took a math class taught by future World War I General John J. Pershing. But she continued publishing, realized that she loved writing, and went into literature instead. For as tightly as Cather as seen with the state of Nebraska, she basically never lived there again after graduating from college.

Cather went to Pittsburgh to work for a little magazine, taught English and literature in local schools, and kept writing. She started getting notice for her fiction and that led to McClure’s offering her a staff position in 1906. That led her to New York City. She wrote her first novel, serialized in McClure’s, in 1912. That was Alexander’s Bridge. Then she went back to her Nebraska roots for the three novels that we really know her for–O Pioneers in 1913, The Song of the Lark, in 1915, and My Antonia, in 1916. These made Cather a literary sensation and she was really the first major novelist of the Great Plains. Part of what made her so great was her fully developed style by this time–there was no artifice. She wrote in plain language for plain people that expressed great power in simple dialogue. This wasn’t the Gilded Age anymore. Writers could just write how they felt and develop character without long digressions or fancy language to make the Brahmin class feel smart. Cather instantly became a legend, someone that great writers such as Sinclair Lewis or F. Scott Fitzgerald loved and compared themselves and their work negatively toward.

The 1920s remained quite productive for Cather. One of Ours, from 1923, won the Pulitzer and was one of the first major World War I novels, although it’s not one often read today. By this time, she was spending a lot of time in New Mexico and like much of the arts colony revolving around people such as Georgia O’Keefe, D.H. Lawrence, and Mabel Dodge Luhan, she found herself enchanted by the place. So in 1927, she published Death Comes for the Archbishop, a late 19th century New Mexico novel about a priest that tries to establish a parish in a small town. A Lost Lady and A Professor’s House were also highly acclaimed.

By this time, Cather was in an open lesbian relationship with Edith Lewis, also buried here. Born in 1882 in Lincoln, Nebraska, they met in 1903 in that town. Cather was in college and Lewis was back from her years going to Smith. They lived together for the rest of their lives, with Lewis having a quite successful literary career of her own as an editor at McClure’s. Today, there is lots of speculation that Cather and Lewis really wrote most of those novels together. I’m not a literary scholar and this is pretty far outside of my field, so I don’t really know, but figured I’d mention it. Interestingly, Cather did not include anything like lesbian themes in her fiction or really any kind of feminism at all. It was her life, but she doesn’t seem to have embraced any kind of political position based on it. That’s not all that surprising given the time. She was also a political conservative and really more of a reactionary, which probably influenced those choices about how to present or not present her personal life as well.

By the 1930s, Cather was falling out of fashion. It happens. As the World War I fiction world grew, a lot of writers, including the misogynist Ernest Hemingway, criticized her World War I novel for knowing nothing at all about war and thus being kind of ridiculous. She became seen as old-fashioned, nostalgic, and too romantic. Well, that’s probably all true enough. Her right-wing politics didn’t help much with her reputation. That’s especially true as the Great Depression hit, the left had greater cultural cache than it ever would before and since, and politics were the name of the game. She kept writing and a lot of those works sold well, even if they were no longer critically acclaimed.

By the end of her life, Cather was writing novels about the distant past. Her last completed novel, Sapphira and the Slave Girl, was published in 1940, and was an attempt by a southern white woman of her time and age to reckon with slavery. This didn’t really romanticize slavery in the way you’d think and was not like some Thomas Dixon hackwork, and in fact was critically acclaimed and sold well. Much later though, Toni Morrison used the book as a prime example of the problems with clueless white authors trying to imagine Black characters. Upon her death, Cather was working on a novel about 14th century France, which is really out of time and place. Lewis destroyed the manuscript on Cather’s orders.

Alas, it was never completed. Cather was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1945 and she died in 1947 after it spread to her liver. She was 73 years old. Lewis lived all the way to 1972 and was 89 when she died.

Willa Cather is buried in Old Burying Ground, Jaffreys Center, New Hampshire. She and Lewis never really lived there, but their friends had a retreat there and they loved it and the quiet and so decided that would be their resting place. Lovely place in the fall, no question about that.

Willa Cather first appears in the Library of America series as the 35th volume in the series, and the second woman, behind Edith Wharton. If you would like this series to visit other writers anthologized in Library of America, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Theodore Dreiser, who is the 36th volume, is in Los Angeles, and Flannery O’Connor, who is the 39th volume, is in Milledgeville, Georgia. Incidentally, Benjamin Franklin has volume 37 and William James volume 38 and I’ve already covered those guys. Previous posts in this series are archived here.