Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,217

This is the grave of Tom Connally.

Born in Eddy, Texas in 1877, Connally grew up on a farm, the son of a Confederate veteran and a mother who died young, though otherwise I don’t know much about his childhood. He went to Baylor University, graduating in 1896, only 19 years old. Then it was on to the University of Texas Law School, where he finished his degree in 1898. He volunteered for the Spanish-American War, avoided the most likely thing to kill him there–yellow fever–and then came back to Texas where he started practicing law in the small town of Marlin.

It took no time at all for Connally to show interest in politics. He was basically a white liberal that supported good social programs for other white people. That described a lot of people at that time who were totally OK with a more active government that helped people so long as they were white. He ran for Texas state legislature in 1900, won, and then won reelection in 1902. He already opposed monopoly and was one of the authors of the Texas Anti-Trust Law in 1903. This was a strong populist.

However, he took a break from politics in 1904. He wanted to make some money and he needed to work on his law practice in order to do that. He became prosecuting attorney for Falls County in 1906 and held that position for the next four years. He continued plugging away at the law until 1916, when he decided for a second foray into politics. The Congressional seat for his district became vacant when Robert Henry, another populist-type, ran for Senate and lost the nomination. It’s hard to imagine today, but this area of north-central Texas was a hotbed of left-leaning ideas, again within the context of white supremacy. Connally ran, won, briefly stepped away to volunteer for World War I (he was still a young guy) and then returned to Washington.

Connally, and this isn’t super surprising given his predilection for volunteering in wars, was a big supporter of the League of Nations and an internationalist perspective for American foreign policy. This made him in a minority in Congress for sure, but it was enough to get him on the House Committee for Foreign Affairs and he was an active supporter of a strong foreign policy through these years. Given that he was from Texas and that so many of the populist-isolationists of the next fifteen years were also populists from western states–Wheeler, Nye, Johnson, etc–if anything it was more likely that his populism, not to mention his anti-Black racism–would lead him to a place where he would see that Jews were leading the U.S. back into war but he very much did not have these thoughts. He was pretty anti-interventionist as well. He criticized the constant invasions of Latin America and urged good relationships with Mexico. Of course he looked out for the Texas beef industry and didn’t want too much importation of Argentine beef, but that was pretty par for the course for a politician who wanted his voters to like him.

In 1928, Connally ran for the Senate and won. Of course, supporting Jim Crow was central to this. And yet, Connally was the anti-KKK candidate for the Democrats, someone who had strong Jim Crow credentials but thought the Klan was an awful organization. His continued populist economics helped. Early in his time in the Senate, he fought Hoover’s attempts to institute a national sales tax (just what workers needed in the Depression!). Then FDR won in 1932 and Connally became one of the biggest supporters of the New Deal, a close Roosevelt ally in the Senate, not to mention one from a key state. A big supporter of the National Recovery Administration, he responded to the Supreme Court ruling the NRA unconstitutional in 1935 by proposing the amusingly named Connally Hot Oil Act, which reestablished the federal ability to regulate interstate shipments of petroleum that effectively reinstated NRA codes in that industry. It passed pretty quickly too. It’s still a law today. Connally however did not support the court-packing plan in 1937.

Sadly, it wasn’t just court-packing that made Connally nervous. He began moving slowly to the right on several economic issues. Much of this had to do with race. He led the filibuster against federal anti-lynching legislation. He supported the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938, but only with the exceptions to the law that cut out any category of worker where Black laborers were in large numbers in the South, i.e., housekeeping, farmwork, child care, nursing.

But what salvaged Connally’s later career was his continued interventionism. FDR might have been getting more frustrated with his increasingly erstwhile Texas ally (though he certainly hated Connally less than John Nance Garner), but when it came to preparation to fight fascism, Connally was right there. He led the fight in the Senate both for the Cash and Carry Act and for Lend-Lease. He became chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1941, which made him an extremely powerful ally both in the years leading up to the war and in the years after it. He was a critical figure in the development of the United Nations and getting people in skeptical states such as Texas to accept it. This required turning back fears that the UN would do things like put pressure on governments to accept racial equality, which let’s face it, it eventually has done, however slowly. He and Truman were close too. Perhaps even more importantly, so were he and Arthur Vandenberg, who would head the committee for two years that Republicans took the Senate between 1947 and 1949. Then Connally came back to chair it when Democrats retook the Senate in the 1948 elections. He was also key in pushing NATO through the Senate.

Again, Connally had shifted to the right on social issues as he aged, especially in the face of rising northern liberalism. He again led an anti-civil rights filibuster, this time to make the poll tax illegal in 1942, when he led a ten-day filibuster (gee if only we could see such democracy at work today!). He also authored the vile Smith-Connally Act which cracked down on unions striking during the war and authorized the president to seize striking plants and force workers back on the job. FDR never used this and he hated the law, but it laid the groundwork for Taft-Hartley Act in 1947, which Connally also voted for. Still, he supported independent nations of people of color for the United Nations and pushed to admit Afghanistan at the UN’s beginning.

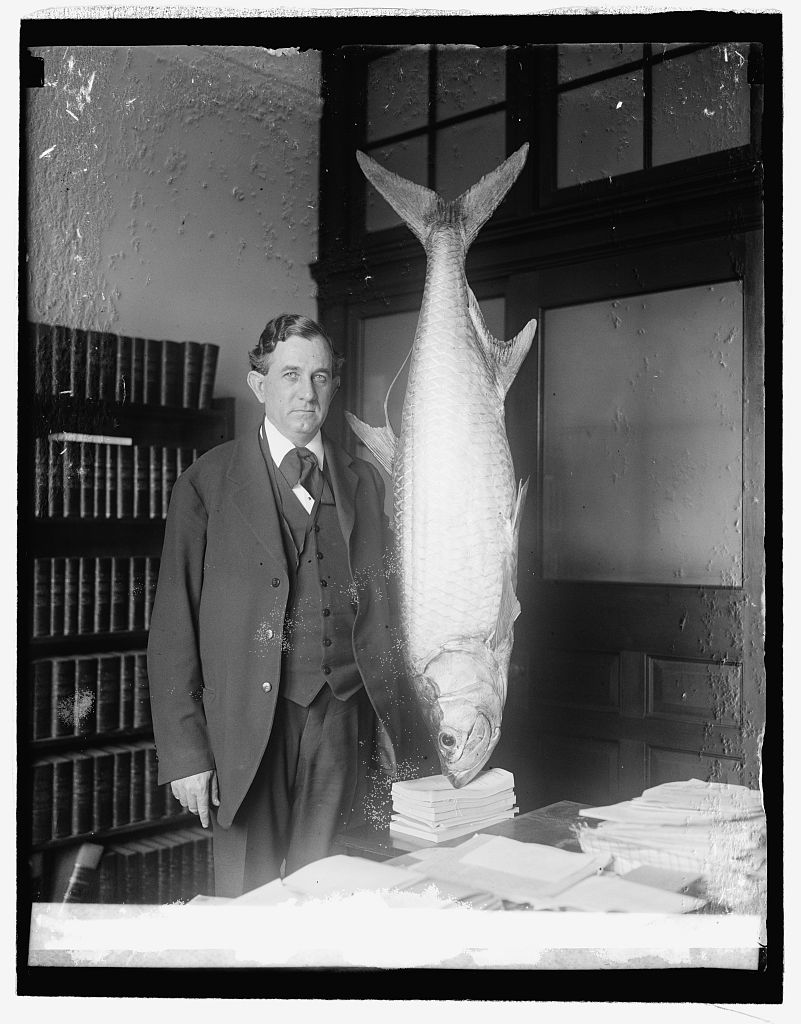

Connally was also known for being a bit of a showboater, a clown, the kind of guy other senators love. This is the root of the Biden nostalgia for seeing Jennings Randolph’s wrinkled penis in the Senate locker room. This was the era of Senate comity, white men hanging with white men, drinking and doing God knows what else. He was known for wearing a toga among other things. Also, here’s Connally with a large fish.

There’s got to be something holding up that fish.

Because of Connally’s long-standing animus with the oil industry, he was targeted in 1952. Texas oil kings wanted to extend state control of oil and Connally didn’t want the companies to control it. Seeing the writing on the wall that he would probably lose the primary after the companies chose M. Price Daniel to run against him and after they initiated a major campaign to link him to the despised Truman, he chose to retire. Connally lived another decade, dying in 1963 of pneumonia. He was 86 years old.

Tom Connally is buried in Calvary Cemetery, Marlin, Texas. This grave is probably the best thing about that town at this point.

I was just in Texas for a conference, which your donations allowed me to expand into a week long trip where I picked up 39 graves. Let’s just say that they are of some, uh, interesting folks……Anyway, this is what you paid for! If you would like this series to visit other heads of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Arthur Vandenberg is in Grand Rapids, Michigan and Alexander Wiley is in Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin. Previous posts in this series are archived here.