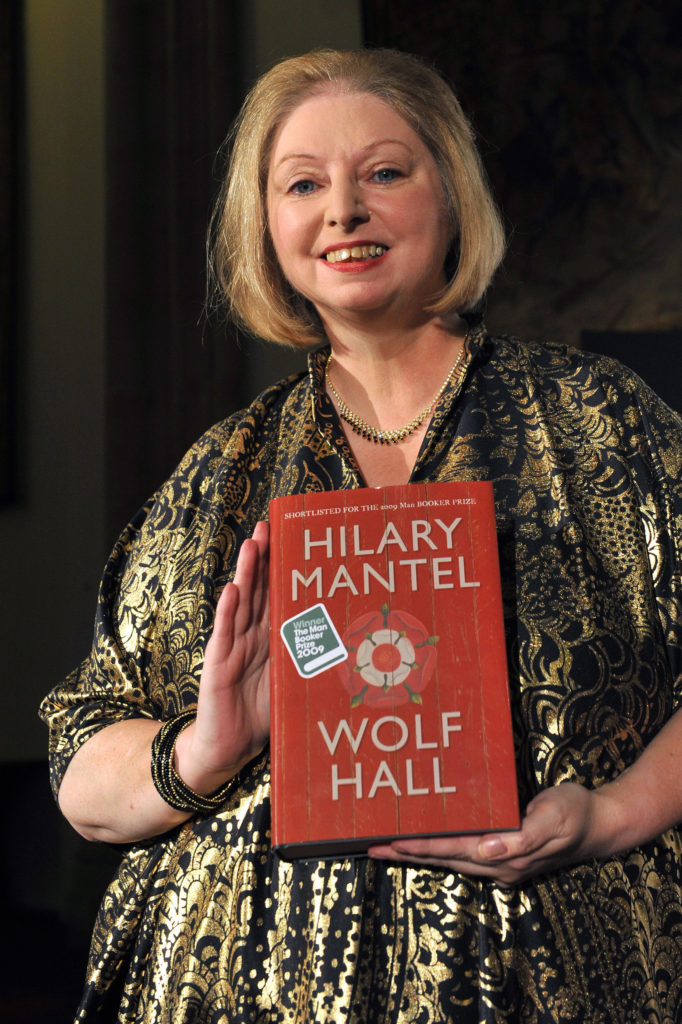

Hilary Mantel

The great novelist died at age 70:

Long before she became a bestselling novelist (and two-time Booker Prize winner) writing about Thomas Cromwell, Hilary Mantel, who died Thursday at the age of 70, had learned two things by direct experience: that authority cannot be counted on and that evil is real. This presented a conundrum to anyone raised Catholic, as Mantel was. Born in 1952, she grew up in the particularly dreary part of northern England, a place where the people were “distrustful and life-refusing,” but where the authority of the church promised an escape from Satan and the general nastiness of life as long as you submitted to it, unquestioning. Mantel gave up on all that at the age of 12, but her apostasy really began when she was seven and encountered a fundamentally indescribable presence just beyond her back yard. “It is as high as a child of two,” she wrote in her memoir, 2003’s Giving Up the Ghost. “Its depth is a foot, fifteen inches. The air stirs around it, invisibly. I am cold, and rinsed by nausea. I cannot move.” What was it? The Devil, probably. At any rate, it seemed more present and powerful than God. She believed this force invaded her, and never truly left her alone afterwards—even the final sentence of her final book of stories published in America, this year’s Learning to Talk, returns to this presence, which “wrapped a strangling hand around my life.”

Mantel—who studied law and was employed as a social worker before leaving England in 1977, when her husband accepted a job in Botswana—suffered for most of her 20s from unexplained pain and fatigue. Her doctors insisted this affliction was psychosomatic, prescribing anti-depressants, sedatives, and antipsychotics, the last of which, she wrote, make you feel like “every fiber of your being is possessed by panic.” In Botswana, she decided to research her symptoms herself and soon realized that she suffered from endometriosis. She returned to England, got a hysterectomy and a divorce. Two years later, she re-married her ex-husband (they remained together for the rest of her life), and she followed him on a new job in Jeddah, in Saudi Arabia, where they lived for four years. It was in Jeddah that Mantel began to write novels, in a country she described in a vivid essay for the Guardian as oppressive and inscrutable, governed by innumerable unwritten rules, where foreigners were regarded as “just a bit of international flotsam with a temporary use and a short expiry date.”

From the first novel Mantel wrote, A Place of Greater Safety (initially rejected by publishers, it was the fifth of her books to be published, in 1992), she showed a liking for figures customarily seen as bad guys. A Place of Greater Safety, set during the French revolution, depicted Robespierre as more sympathetic than the romantic revolutionary, Danton. This seems less a matter of ideology than a stubborn resistance to conventional wisdom, since the inflexible moral purity of Robespierre, when embodied in the person of Thomas More in the Wolf Hall novels, is depicted as deplorable in the eyes of that consummate pragmatist, Cromwell. “I am glad I am not like you,” Cromwell tells More, who was executed in 1535 for refusing to validate Henry VIII’s separation from the Catholic Church. “I mean, my mind fixed on the next world. I realize you see no prospect of improving this one.”

I didn’t actually know that Greater Safety — a novel I’ve always liked, without claiming it’s the equal of the Wolf Hall trilogy — was her first-written novel. R.I.P.