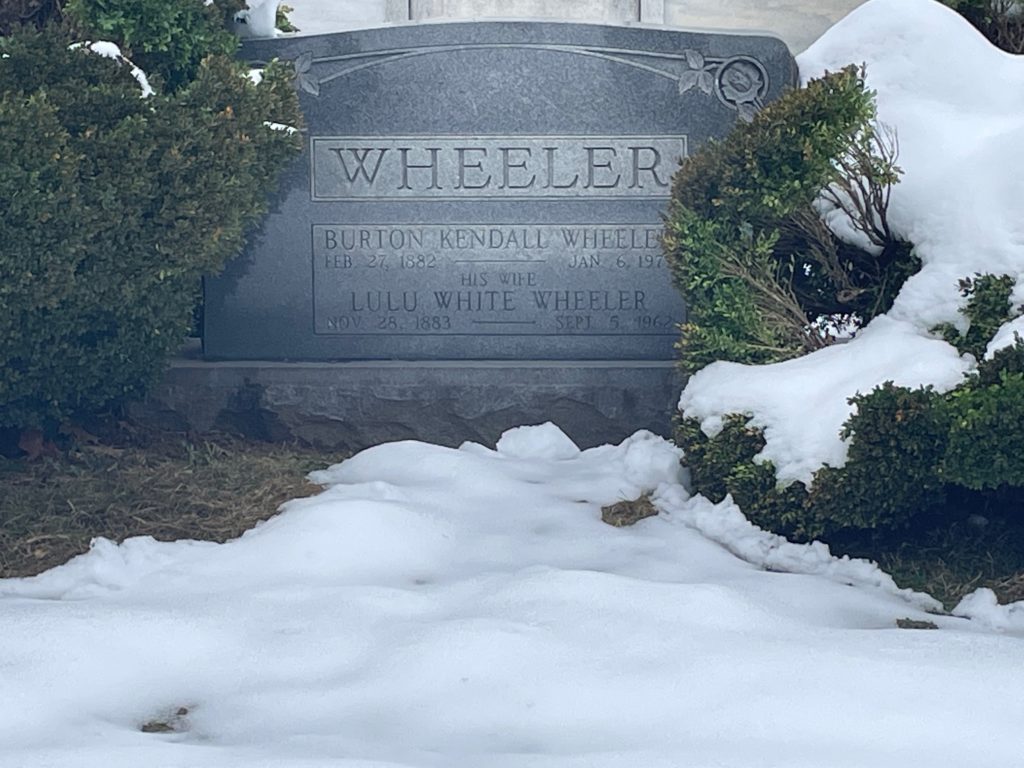

Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,207

This is the grave of Burton Wheeler.

Born in 1882 in Hudson, Massachusetts, Wheeler attended the public schools of the state, worked in Boston for awhile as a stenographer, then moved to Michigan for law school. He got his degree from the University of Michigan Law School and finished there in 1905. Adventurous and looking for opportunities in the West, he intended to move to Seattle and start practicing there. But he didn’t get that far west. While in Butte, a pretty wild mining town, Wheeler got in a poker game. It didn’t go well for him. Not only did he lose all his money, he gambled away most of his possessions too. So he had no choice but to stick around for awhile and earn some money to continue his journey. So he set out his shingle in Butte and then ended up liking it. He decided to stay in Montana.

Butte was a copper town and the Copper Kings still controlled the state. Montana politics revolved more around how you stood on the copper capitalist question than political party. Either you were a bought and sold man of the copper companies or you rose to fight against them. Many were bought and sold enough that William Clark literally bought his way to the Senate, which led to him being kicked out and the Seventeenth Amendment was ratified in response to this overt corruption. Wheeler was one of the people who rose in opposition to copper’s control over the state.

Moreover, Wheeler came to prominence in Montana as one of the only people in power willing to resist the repression of civil rights for workers that came after the Speculator Mine fire and the subsequent lynching of IWW organizer Frank Little in 1917. Shortly after, Montana and Northwestern states combined to engage in a coordinated plan to crush the IWW and suppress civil liberties. Wheeler was a U.S. Attorney at this time and he refused to participate. He certainly wasn’t able to stop this from happening in Montana, but his principled stand in favor of free speech caught the attention of civil libertarians around the nation.

In 1920, Wheeler decided to take advantage of his new fame and try to become governor of Montana. He ran as an open liberal at a moment when the Red Scare hadn’t quite faded. He did win the Democratic nomination and he worked to bring the tribes into his political coalition. Not all could vote until 1924 but many were already moved into citizenship rights due to the allotment of their land under the Dawes Act. Part of his Democratic ticket included a Blackfeet candidate for state legislature, as well as a Black candidate. Wheeler didn’t win this election but he did prove a strong candidate.

So in 1922, Wheeler decided to take another bite at the apple, this time going for the Senate. He won and immediately made a splash in the Senate as taking the lead in investigating Teapot Dome and the reticence of the incredibly corrupt Harding administration in doing anything about it. Harry Daugherty, the grotesquery at Attorney General had Wheeler investigated for being a communist, was a very far from true. He was a liberal who believed in free speech and that’s it. This was a total hit job. The “findings” had no real impact on Wheeler’s career and just made Daugherty look even worse, somehow. His left-liberalism, good governance, pro-civil liberties politics made him a hero to a certain type of reformer and Robert LaFollette chose him to run as VP on his 1924 Progressive Party ticket. Democrats were obviously not thrilled by this, but party discipline wasn’t anything like it is in the contemporary Senate a century ago.

Wheeler came back into the Democratic fold. But he suffered from a common disease plaguing the Progressive Era liberal–the New Deal broke him. At first, he supported FDR. He liked much of the early New Deal and had advocated for social programs. But the court-packing plan completely destroyed Wheeler’s opinion of Roosevelt and he turned on the president pretty strongly from there. Changing the Court wasn’t much different in Wheeler’s head than the corporations seeking to suppress speech back in 1917. Then, FDR moved the nation toward intervention in World War II.

Wheeler could not deal with the U.S. being involved with the rest of the world. He was a true isolationist, as were a lot of these western populist types. As good as he was on a lot of issues, Wheeler simply did not recognize–or didn’t care that much–about the threat of overseas fascism. He held on to the idea that the U.S. should have no interaction with these “entangling alliances” to quote Washington’s Farewell Address. And so he reacted with horror to things such as Lend-Lease. He became one of the most notorious isolationists in the nation, to the point of being called out in Woody Guthrie songs as a friend of Hitler. That wasn’t true, but Wheeler wasn’t going to do anything to stop Hitler or anyone else if it involved Americans fighting overseas. Moreover, he spoke to America First and began to embrace anti-Semitism, launching the Wheeler Committee to investigate foreign influence in Hollywood, i.e., Jews.

Those who opposed this era of Roosevelt were looking for a third party challenge in 1940 and John L. Lewis tried to get Wheeler to run for president, but the senator did not. By this time, Wheeler came under attack from both FDR and Wendell Willkie, who claimed Wheeler was a Nazi who wanted to put the same censorship on Hollywood that Hitler did in the German film industry. It got so bad that the Nazi Party in Germany moved money toward Wheeler’s election campaign. He begrudgingly voted to join World War II after Pearl Harbor but remained suspicious of all things that would involve America in the world.

Wheeler remained in the Senate, increasingly isolated, through the war. He was one of seven senators to vote against the U.S. joining the United Nations in 1945, which is an almost insane devotion to the foreign policy of a century earlier. In 1946, Wheeler was challenged from the left in the Montana Democratic Party and lost to Leif Erickson. But Republicans took the seat in the general.

Wheeler’s later years in the Senate are a sad story. But he did go some way to redeem himself after he left the Senate. He was as horrified by the House Un-American Activities Committee as he had been about civil liberties violations during World War I and served as counsel to some politicians forced to testify before HUAC. He also did not return to Montana. Many long-time western politicians, even today, just stay in DC after their political careers end and thus are buried there. Wheeler opened a law practice in DC and worked for the next couple of decades. He finally retired and died in 1975, at the age of 92.

Wheeler’s historical image is so damaged that when Philip Roth wrote The Plot Against America, he placed Wheeler as Charles Lindbergh’s VP and who enacts martial law while serving as active president. Wheeler’s career to me is just sad, a man who was good on so many issues but who was so terrible on a few that he torpedoed his entire contribution to America over them. Anti-Semitism and isolationism are just strong drugs I guess.

Burton Wheeler is buried in Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, D.C.

If you would like this series to visit other isolationists before World War II, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Charles Lindbergh is in Maui (oh please don’t send me there….) and Arthur Vandenberg is in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Previous posts in this series are archived here.