Black History and “Presentism”

The idiot president of the American Historical Association, James Sweet, permanently destroyed his reputation in much of the profession through his ill-thought out essay on “presentism,” in which he didn’t do anything even close to providing a historical argument with evidence, only cited the 1619 Project as bad, and gave the far-right fodder for their culture war. He probably meant to do none of this, but no one is worse at interacting with the public than big name historians who think every word they write is gold and aren’t used to having their statements really critiqued by the general public. Well, it’s his reputation. And not surprisingly, this has opened up the opportunity to defend politically charged histories by the historians who write them. As Keisha Blain, one of the finest U.S. historians working today, notes in The New Republic, activist Black history exists because actual Black people are literally fighting for their lives.

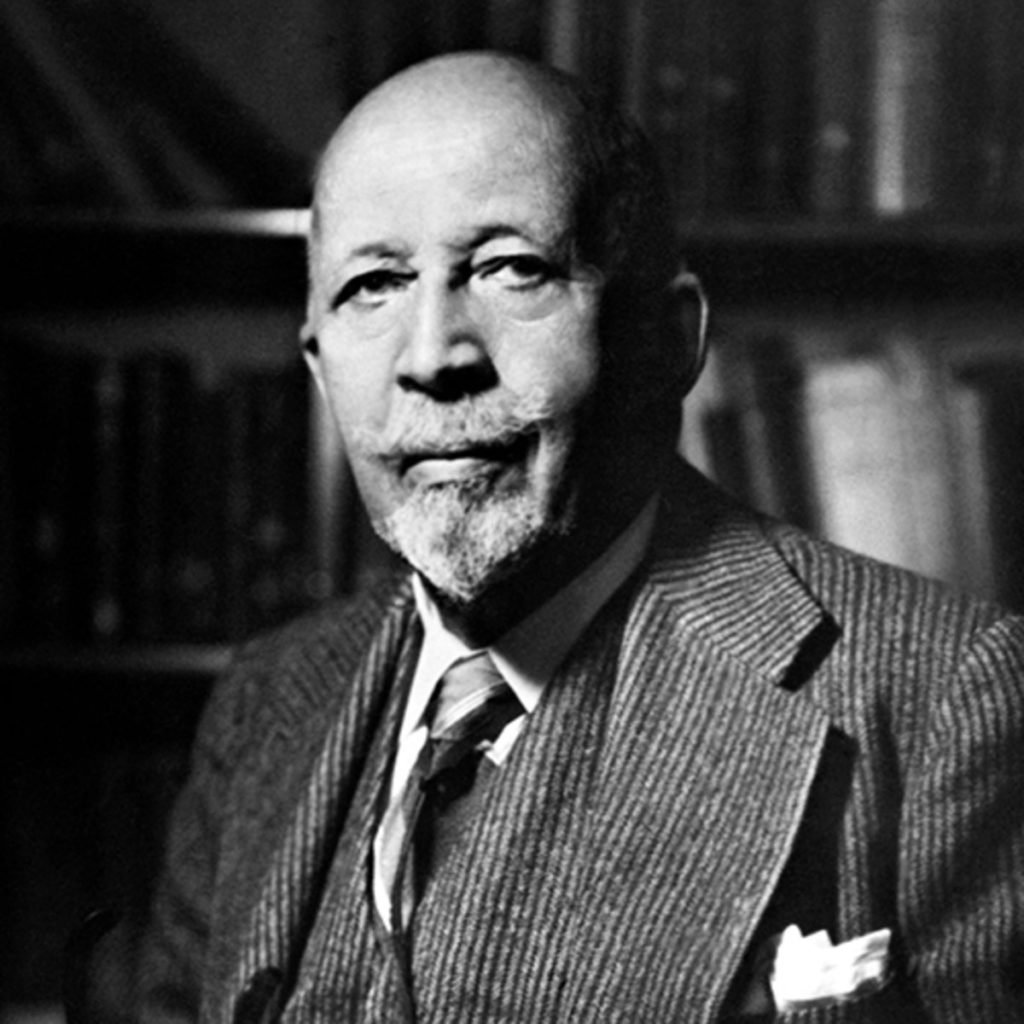

The Dunning School’s interpretation of the past was very much shaped by present concerns at the time. They used their writings on the past to justify—and give moral validity to—the mistreatment of African Americans. The scholarship of these historians served to reinforce segregation and racial discrimination in the U.S. during the early twentieth century. White policymakers, educators, and others cited the racist interpretations of the Dunning School to further limit Black access in the public sphere and to uphold stereotypes. The same scholars decrying “presentism” today most likely would have framed Du Bois’s powerful rebuttal in the same manner—as some of his critics did. But were it not for scholars like Du Bois, we would still be relying on the white establishment’s racist accounts of Reconstruction.

Du Bois’s response to the Dunning School, as well as the efforts of Anna Julia Cooper and Carter G. Woodson, exemplify how Black historians have taken an active role in confronting political abuses of the past. They were not alone. Marion Thompson Wright, Dorothy Porter Wesley, and Merze Tate were among the first generation of professional Black historians who used their writing and research of the past to address myriad contemporary social issues. They recognized, as Manning Marable, the founding director of the Institute for Research in African-American Studies at Columbia University, observed in 1998, that “scholarship and social struggle cannot be separated.”

Indeed, historians do not produce scholarship in isolation. The work we do has the potential to shape national debates and inform policies that have broad implications for all Americans. The weight of this responsibility is especially great for members of marginalized groups. In a white-dominated world and academy, we are always fighting to assert our voices and our histories into spaces designed to exclude us.

More importantly, we are fighting for our lives. The commitment to engaging present concerns is not simply a method or approach to the scholar’s craft of research and writing. It is a matter of life and death. The reality of the present moment propels many of us to act. In the spirit of Du Bois, Woodson, Cooper, and others, we have a duty to lend our expertise to the most pressing issues of our day. It is not only logical and responsible to do so; it fulfills the underlying mission of historical study in communities of color to illuminate the complexity of our lived experiences.

What amazes me, but doesn’t actually surprise me, is how certain historians–usually white and quite often at elite schools–can turn “objectivity” into a fetish that forgets the most important fallacy of it–that if you claim to be “objective” you are also making a political choice about how you write on the past based on your general acceptance of the society in which you live. But of course that’s just “normal” unlike those hippies like DuBois or the 1619 Project people.