Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,170

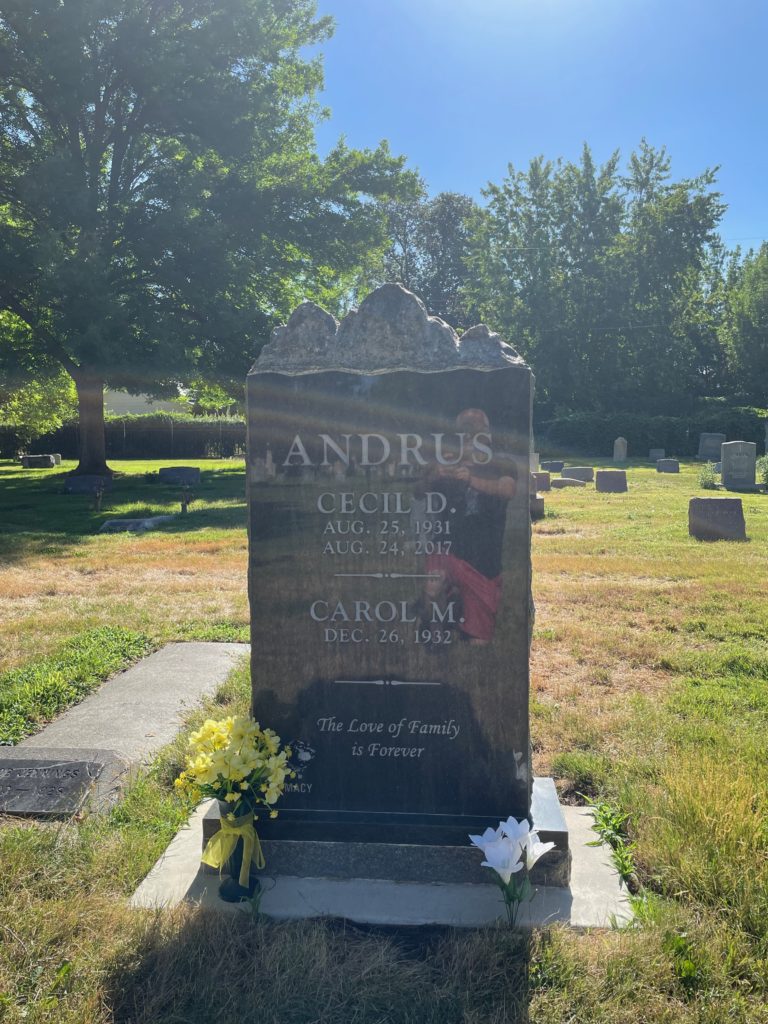

This is the grave of Cecil Andrus.

Born in Hood River, Oregon in 1931, Andrus and his siblings grew up near Junction City, Oregon, just outside of Eugene. This was a very poor family. The farm didn’t even have electricity. That’s hardly surprising for rural Oregon in the 30s, even western Oregon, which was a lot more advanced than eastern Oregon. During World War II, they moved to Eugene, where his father and uncle started a business refurbishing sawmill equipment. In any case, there was little reason for the young Cece, as his friends would call him all his life, to become the powerful figure that he in fact became. He did well in school and enrolled at Oregon State University in 1948 to major in engineering. But he dropped out after the first year as he had a job working in the local utility industry. He was in the Naval Reserves during the Korean War and was active for much of the time between 1951 and 1955, working as an electronics technician. In 1955, he was discharged and he moved to Orofino, Idaho, taking a job in the timber industry. The mill closed in 1962, he got a job in insurance, and he moved to Lewiston in 1966.

At this point, we are basically talking about an older version of my father. Here he is, a 35 year old, no college education, some time in the Navy, working in the timber industry, now laboring in insurance. And heck, by 1966, my father was back in Lewiston too, more or less. Maybe they ran into each other! But Dad would not end up as governor of Idaho, like Cece would just a few years later.

Andrus’ interest in politics came pretty young. He was a staunch New Dealer and he felt, as did many rural populists at the time, that the countryside was getting screwed over by the cities. Now that’s just as common today. There’s nothing inherently right-wing about populism. The question is whether populism comes with a class consciousness. That’s something that Andrus had. He thought Republicans were the ones screwing over the countryside. He ran for the state senate against some Republican who didn’t support education funding for rural schools the way Andrus thought it should be run in 1960 and he defeated him, winning reelection in 1962 and 1964. Yes, he was a millworker/legislator.

In 1966, Andrus, who was nothing if not ambitious, decided to run for governor of Idaho. He was only 35 years old. But he lost the primary. However, the winner of the primary thereafter had a helicopter crash and died. Andrus was given the replacement slot on the ballot and he proceeded to lose to the Republican. But all of this did not hurt his statewide profile, even if he lost both the primary and the general.

Idaho was not a liberal state, but it could elect liberal politicians if they were people who could speak to rural voters. This was Andrus’ gift. But he wasn’t alone. This was the Frank Church era as well. Northern Idaho, today one of the farthest right regions in the country, was New Deal country and while we can talk about white backlash destroying the New Deal coalition, these voters cast their ballots for pretty liberal Democrats at least some of the time for a long, long time after LBJ signed the Civil Rights Act in 1964. Andrus most certainly could speak to those voters because he basically was one of them. He returned to the state senate in 1968 from a seat in Lewiston and then won the 1970 governor election over the man who defeated him in 1966. An Idaho political legend was born.

Andrus won reelection in 1974. He was a strong environmentalist and a moderate on social issues. He was personally anti-abortion and made that central to his image, but also did not overly protest when Roe made abortion legal. He took the mantle of an environmentalist in a state where hunting was a dominant activity. Part of the reason he could do this is that he was personally an avid outdoorsman, including hunting. The big issue roiling Idaho politics during the early 70s was the proposal to turn the Sawtooth into a national park. This was a complicated issue. From a scenery standpoint, it’s equal to Glacier. Having hiked up there earlier this summer for the first time, it’s pretty mindblowing. Many environmentalists wanted a national park. So did many developers. Other environmentalists worried about roadbuilding and loving it to death. Andrus steered this conversation, ensuring protection for the most important part of the range. In the end, the center of the Sawtooths became a wilderness area and then there was a larger National Recreation Area for the region, which doesn’t preclude too much development but still works to keep the basic character of the region.

It’s not surprising then that in 1977, Jimmy Carter tapped Andrus to become Secretary of the Interior. Carter’s best legacy as president is environmental and Andrus was a key part of this. If anything, he was even harder charging on this than the president, sometimes having ideas that would cause some consternation within the party and that Carter would reject. But they worked closely together on Carter’s signature bill to protect large swaths of Alaska permanently, controversial in that state over four decades later. Andrus also led the way on expanding Redwood National Park in California, which is the start of the timber wars in the Northwest dividing environmentalists and workers. Andrus was one of the only Cabinet members to the last the full four years, after Carter kept him on after forcing the resignation of the entire Cabinet in a 1979 purge.

Andrus returned to Idaho in 1981. He was still young and active. And he wanted back on the stage. So he ran for governor again in 1986 and won another two terms. He was always pretty irascible, a straight-shooting no-nonsense guy from Idaho who would tell off other politicians, as I highlighted not long ago when I was doing research in his papers and he basically told Alan Simpson to go fuck himself in no uncertain terms. At some point, he was kicked in the head by a horse while on a hunting trip, which only made him more cranky. Here, his main policy goal was keeping the federal government from using Idaho as a nuclear waste dump and he went so far as to ban the shipment of nuclear waste through his state, which was probably not actually illegal. It was around this issue that he told off Simpson. He also, despite still being personally anti-abortion, vetoed a 1990 bill that would have basically overturned Roe in his state. Like Harry Reid, Andrus was a social libertarian, realizing that his personal beliefs should not be made policy. Salmon was also a major part of his legacy and with runs rapidly declining in Idaho, he started the push to get rid of the nearly useless four Snake River dams in eastern Washington. That’s never happened, in part because people in Lewiston are so proud of their idiotic ocean-going port 500 miles from the sea. But it is still part of the conversation today at least.

In 1994, Andrus decided not to seek a fifth term as governor. Probably he read the writing on the wall. It’s possible he might have survived the Republican wave that year. If anyone was going to do so in a state like Idaho, it was Andrus. But this was also the election that the proto-Boebert/Palin lunatic Helen Chenoweth ousted the moderate Democratic congressman Larry LaRocco and the northern Idaho Democratic base turned far to the right, where it has remained, so maybe not.

After his retirement, Andrus served as a senior figure trying to create common sense solutions to problems. With a long history of bipartisan work, he had the ability to do this and he could at least get people together to talk through issues at his center at Boise State University. But there was increasingly little room in American politics for a working class Democrat like Andrus. But he held rallies, worked for candidates, and was a senior figure nationally until close to the end.

Andrus died in 2017, at the age of 85.

Cecil Andrus is buried in Pioneer Cemetery, Boise, Idaho.

If you would like this series to visit other Secretaries of the Interior, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Thomas Kleppe is in Arlington and Stanley Hathaway is in Torrington, Wyoming. Previous posts in this series are archived here.