China’s stumbles won’t revive U.S. global hegemony

China might be headed toward a recession.

Against all expectation (not a single economist polled by Bloomberg had predicted it), the People’s Bank of China has cut interest rates. The ease was only by 10 basis points, to the bank’s one-year lending rate, but it was still in the exact opposite direction to the monetary route being taken in the west and in the rest of the emerging markets. And the PBOC would assuredly not have done this unless it felt compelled — which implies that the central bankers believe the Chinese economy is in a worse state than it appears.

Various indicators show a slowdown in Chinese growth. The real-estate market, however, is getting hammered.

China’s home prices fell for an 11th month in July, underscoring how government relief efforts are failing to curb the country’s spiraling real estate crisis.

New home prices in 70 cities, excluding state-subsidized housing, declined 0.11% from June, when they sank 0.1%, National Bureau of Statistics figures showed Monday. Existing-home prices fell 0.21%, the same as a month earlier.

China’s $2.4 trillion new-home market is showing little signs of recovery, adding to the woes of an economy that barely expanded last quarter. The mortgage boycotts, which emerged from early July, are dampening consumer confidence.

Indeed, concerns about China’s economic prognosis help account for recent declines in oil prices—both because of expectations about demand in China itself and what it means for the possibility of a global recession.

For those of us who lived through the 1980s and 1990s, it’s tempting to see an analogy between what’s happening in China and the forces that drove Japan’s “lost decades.” From what I can tell, the majority of analysts are skeptical of this comparison. As a researcher at for the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco wrote back in 2015:

China’s transition to a “new normal” period of slower growth naturally draws comparison to other countries’ historical economic development. Given its recent experience with rapid credit expansion, build-up in real estate, and stock market volatility, some observers wonder whether China faces a “lost decade” like the one Japan experienced following the collapse of its bubble economy in 1989-90. This comparison, while easy to make on the surface, is inappropriate. Invoking Japan’s past as China’s future merely contributes to a misunderstanding of the challenges China does face and a misremembering those Japan encountered a generation earlier.

The China of 2015 does have some fundamental similarities with Japan of the late 1980s. Like Japan before it, China’s rapid modern development relied largely on exports. Credit has grown dramatically, over 100 percentage points since the global financial crisis to over 250 percent of GDP. Asset prices, particularly in real estate, are up significantly over the past decade. Meanwhile, like Japan in the 1980s, China has begun to grow old, with its working age population shrinking after a long period of favorable demographics

Creehan finds the analogy unpersuasive, for reasons that appear in more recent discussions: Japan in 1989 and 1990 was much more “developed” than China is today, China benefits from decades of additional policy experience, and so on. But not everyone is sanguine about the comparison:

“China has an even more extreme version of the Japanese imbalances,” making it harder to rely on consumption for growth, said Michael Pettis, a finance professor at Peking University, in an email.

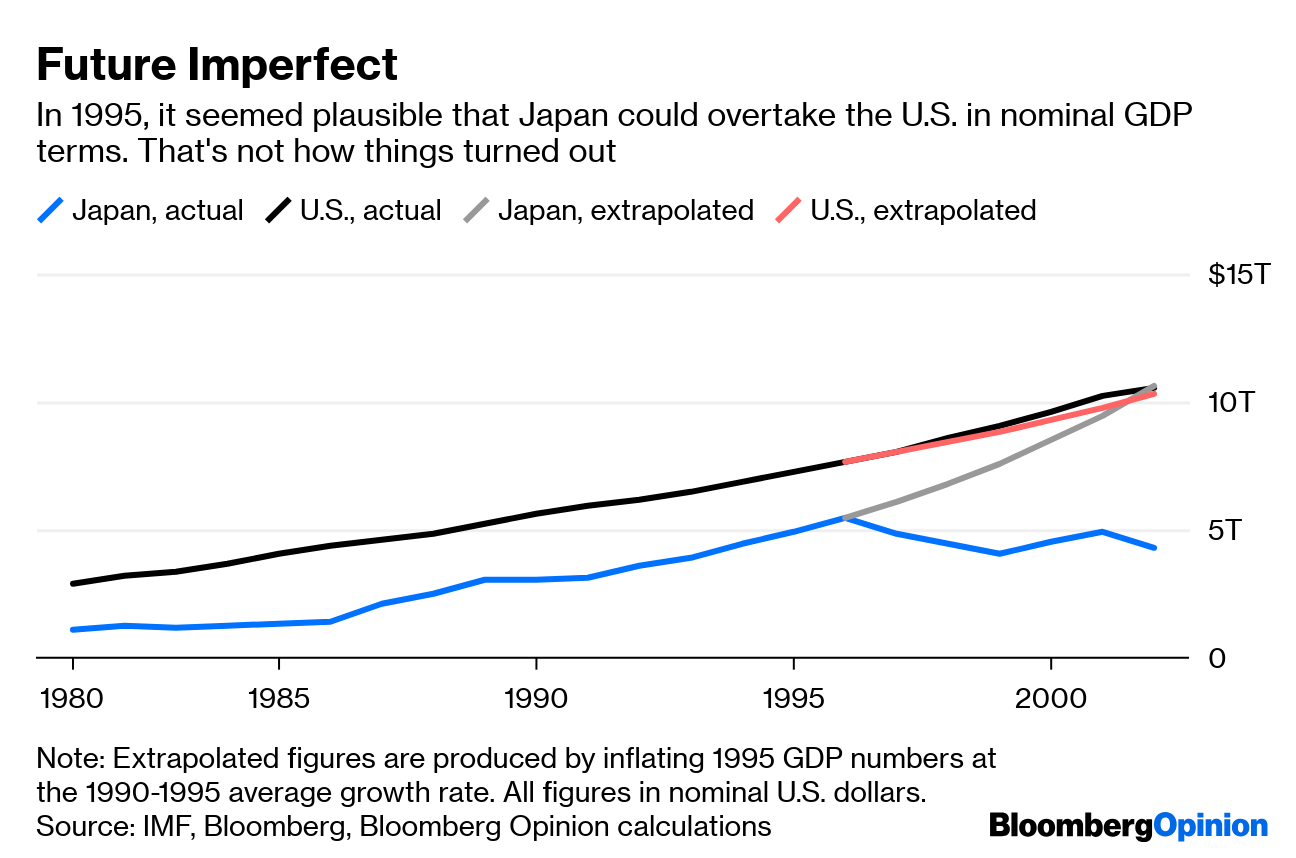

Japan’s economy has stagnated, generally growing more slowly than the U.S. and China since the 1990s, following the burst of a bubble in stocks and real estate.

Japan grew rapidly in the 1970s and 1980s thanks to high growth in exports and infrastructure investment, but by the early 1990s the country was increasingly investing in wasteful projects, said Pettis.

He said Japan has not been able to turn to its consumers to drive growth — primarily because the manufacturing sector has not been able to accept the needed transition to higher wages.

China won’t necessarily follow Japan’s path — if China can make substantial changes to its political institutions, Pettis wrote in April.

But he said the more likely scenario is that China doesn’t enter a financial crisis or sharp economic crisis, and instead is more likely to “face a very long, Japan-style period of low growth.”

If nonproductive investment — primarily in infrastructure and property — is reduced and not replaced with an equivalent source of growth, Pettis estimated China’s GDP would grow by no more than 2% or 3% annually in coming years.

These are the kinds of numbers you expect in a country like the United States. If that becomes the “new normal” for China, though, we might be looking at an inability to escape the so-called “middle-income trap.” That rate of growth may prove insufficient to ensure China’s political stability.

But even if China does experience a period of stagnation, the geopolitical consequences are likely to be very different than those of Japan’s “lost decades.” It won’t mean a reversion to unbridled U.S. global dominance.

First, when American declinists fretted about the rise of Japan in the late 1980s and early 1990s, they were looking at projections that showed the Japanese economy overtaking the United States sometime in the 2000s. The Chinese economy (adjusted for PPP), however, is already larger than that of the United States.

Second, while the 1980s saw increasing US-Japanese tensions over trade and burden-sharing, the two countries remained parties to a longstanding military alliance. Starting in the middle 1990s, China’s growing power pushed Japan and the United States to mend their relationship—at a time when it was not obvious that Japan would suffer from prolonged stagnation.

This matters because, as I’ve noted before, U.S. unipolarity didn’t result from the absence of possible great-power competitors. The U.S. was a unipolar power because the vast majority of second-tier great powers—including Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and Japan—decided they preferred life on the inside of the U.S. security system. If they’d wanted to challenge the United States, we wouldn’t be talking about the 1990s and 2000s as a period of U.S. global hegemony.

China, in contrast, is currently challenging U.S. leadership.

So if you’re counting on Chinese economic woes to revive U.S. global hegemony, you’ll need to wait on something much worse than relative stagnation.