“If ‘freedom’ coerces you into living a particular way that others have determined ‘correct,’ well that is a highly conditional freedom indeed:” A Discussion With Music Critic and Author David Cantwell about Manly Footwear, Fightin’ Sides and Listening to Merle Haggard

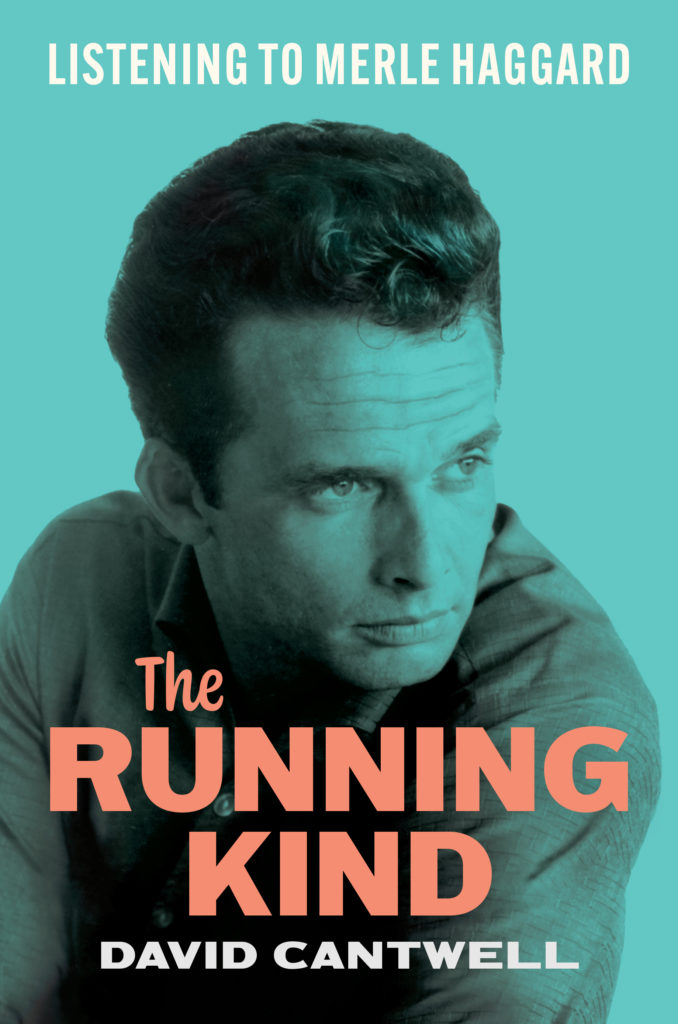

A very few songwriters have ever as fully inhabited the consciousness of the American mind quite like Merle Haggard. The endless compassion and simmering anger of his greatest songs trace the competing impulses towards mercy and cruelty which soundtracks the manic-depressive character of our culture. Haggard is at once the truest believer and the worst pessimist imaginable. He is, finally, perhaps like America itself, unknowable. At the end of the day, the worlds he built, the remarkable personal rubicons he crossed and the staggering richness of his catalog are all that truly matter. We can’t figure it all out today, but we sure can celebrate his music, on this fraught eve of our July 4th celebration. I sat down with David Cantwell, author of the recently updated Haggard treatise The Running Kind: Listening To Merle Haggard. It’s a remarkable book by one of Merle’s most astute scholars and I could not recommend it more strongly. Cantwell is a longtime freelance music critic. His work has appeared in New Yorker, Rolling Stone Country, L.A. Times, No Depression, Slate and many other publications. He’s the coauthor, with Bill Friskics-Warren, of Heartaches by the Number: Country Music’s 500 Greatest Singles. I’m told he hails from Kansas City.

EN: You and I both concur that Merle Haggard ranks alongside Cole Porter, Hank Williams, Smokey Robinson or any other giant of 20th century American songcraft. But you feel he is often not accorded this level of gravitas. It’s a complex question, but do you have a sort of broad strokes explanation for why that is?

DC: Yeah, in my book, I include Holland-Dozier-Holland on that list as well. When people say who’s the greatest American songwriter, I always say Holland-Dozier-Holland — that’s my answer. But those people you mentioned are great. Chuck Berry, did you mention him? He should be there, too.

EN: Sure.

DC: But why is it Merle doesn’t get included in that category? I think what it comes down to, partially, is that he lived too long to die tragically. And I think also country is still the single most maligned of the major pop categories. Maligned, or ignored and neglected. One of the reasons Hank Williams gets included is because he died young, and a legend built up around him. But his country connections are also overridden because lots and lots of non-country artists covered his songs. Haggard’s songbook too is full of widely covered songs which should help him get into that best-of-the-best-songwriters conversation. I’ve been posting great covers of Haggard songs on Facebook and Twitter and I’m collecting them in an ongoing playlist on YouTube. It’s full of just great versions of Merle Haggard songs done by country acts, of course, but also by pop singers, rock singers, soul singers, reggae singers, blues singers and just about every other genre imaginable. But it hasn’t been enough for him to overcome the bias against country generally and, of course, then there’s “Okie…”

EN: Let’s talk about “Okie from Muskogee.” This is the song that Merle is most famous for, and it’s one that seems to soundtrack a certain provincial rage that continues to resonate meaningfully in our culture today. And yet there’s this certain mischief to the song as well and maybe even a subtle note of parody. Can you speculate about what Merle’s intentions were with his signature song?

DC: In the moment before “Okie” came along in August 1969 and made the country charts in October, Merle was really being embraced by the rock audience. His songs were being covered by rock and pop and soul acts. The Byrds covered him. The Grateful Dead played “Mama Tried” at Woodstock. Look magazine said “Mama Tried” should be a pop hit, and a number of rock-and-pop oriented publications had written about him. It seemed like he might experience the sort of crossover traction that his Capitol labelmates Glen Campbell and Bobbie Gentry had or that, say, Jeannie C. Riley achieved at the time. But while “Okie” became a huge hit on the country charts, and a minor pop hit, it also wound up stalling his crossover momentum. To many listeners, the song seemed to drip with a contempt for a youth culture that had embraced him.

But I think his intentions for the song were quite different from what the song became. The story that he settled on — and I still don’t see any real reason to dispute it — is that when he wrote the song originally it was a joke. He and his band were just messing around on the tour bus. They saw a sign along the highway that said Muskogee was coming up and somebody on the bus joked: I bet they don’t smoke marijuana in Muskogee. Presumably because some of the guys on the bus were smoking pot, right? And then they begin to sort of brainstorm what other things they didn’t do in Muskogee. It’s pretty clear listening to the song that they’re coming at their list of things that people don’t do in Muskogee from a much more worldly perspective, a much less provincial view. And much of what the song says people in Muskogee do is presented comically. “Pitching woo” is exaggeratedly old fashioned. The reference to “manly footwear” lands like a punchline. It is definitely poking just a little bit of friendly fun at people from Muskogee. Now, I don’t think the song is mean-spirited at all. Merle knows these people and likes them. They’re his people — they’re working class, they’re patriotic and there is a dignity to their dogmas. “We like living right and being free”– I’ve always imagined Merle intended that as a kind of dark joke because it comes off as a contradiction in terms: If “freedom” coerces you into living a particular way that others have determined “correct,” well that is a highly conditional freedom indeed.

EN: That’s super interesting.

DC: So Merle, who of course had served time in prison and had spent so much of his life running from authority figures and social convention, almost certainly considered the song to be a joke on some level. But then they went out and started playing it live, and audiences did not take it as a joke at all.

EN: A lot of his core audience took every word seriously.

DC: Practically all of them did. At that point, I think Haggard’s original motivation for the song went out the window and he embraced the song the way his audience had, as something much more earnest. We can see this evolution in real time. Shortly after the record comes out, he’s on a show called Music Scene on ABC, guest hosted that week by Tommy Smothers. After Sly Stone opens the show, Smothers turns his introduction of Merle into a joke—and Merle into its butt. He says Merle’s appearance on the typically “really groovy” program has been legally required by equal-time provisions, then he mimes a hit off a joint. But the performance Merle gives, which really approximates the studio recording of the song, is gently folkie and clearly self-deprecating. He’s almost like: “I know this is corny and silly.” He does some eye rolling—at the citizens of Muskogee, at himself. He doesn’t present it as an angry song at all but as a slight, funny little number full of observational humor. So, moving ahead, whenever Merle sang “Okie from Muskogee,” it was always an open question as to how he meant it and how listeners should use it. Are we supposed to sing along with our hand over our heart, or with our tongue in our cheek? And I think the closest-to-correct answer is both.

EN: Merle had actually planned to follow up “Okie From Muskogee” with this beautiful song “Irma Jackson,” which is a crushingly sad song about an interracial love affair destroyed by disapproving societal forces. But after “Okie” is such a huge hit with country audiences, he changes tack and decides to release “The Fightin’ Side of Me” as a follow up, which sort of consolidates a reactionary fanbase. I’m wondering if there is a counterfactual history where that decision doesn’t get made in Merle’s legacy is regarded differently?

David: I think there is. You know, “The Fightin’ Side of Me” is the angrier and completely unironic version of “Okie,” right? No winking in “Fightin’ Side.” It’s a killer groove but a pretty reprehensibly jingoistic sentiment. And I do think that if Merle had released “Irma Jackson” at that moment, his whole career—and maybe even country music history—might have unfolded differently. First of all “Irma Jackson” is a great pop record and would have fit in well on radio at that particular moment alongside records by Brook Benton or Glen Campbell or CCR. I think “Irma Jackson” would have been a legit hit. Johnny Cash told Merle it was going to be a smash when he went to him for advice.

I think Cash was right. There surely would have been push back to the song from a certain part of Merle’s audience. But it is a brave song, coming just two years after the Loving decision, and I think a lot of people would have respected that tremendously while also finding its melody irresistible. And then what? I’m not sure people would remember “Okie” so much as a flashpoint any longer. If “Okie” had been followed by “Irma” instead of “Fightin’ Side,” it would have changed how we hear it. We would have seen “Okie” as more gentle, more tweaking of provincialism rather than as an embrace of reactionary tradition.

EN: There’s something implicitly tolerant about Merle’s lyrics, even at his most strident. It’s weird.

DC: Totally weird. And Merle continued to write and record songs about race throughout his career. I wish more people knew his song “The Immigrant,” for example, from the late ‘70s, which he co-wrote with Dave Kirby, and which not only embraces immigration but explicitly embraces illegal immigration, encouraging the border patrol agents to look the other way when Mexicans come into the United States to work. It’s a remarkable song in a number of ways.

Those impulses to look at race more generously were in him and so I wonder if he had achieved a big hit on country radio and on the pop charts with “Irma Jackson,” set that precedent, then what would other artists have felt empowered to do? If you start to sing about racial issues and having hit country songs with them in the process, what else changes? Do more black artists get to make it on to country radio? Would Charley Pride, who had hits with other Haggard songs, say: “Oh, that was a number one hit? I’m going to cover it on my next album and turn Irma Jackson into a white lady.” I think a lot of stuff could have been different. Obviously, this is all cloud talk, right? Because Merle didn’t actually release it for years, and then only as an album cut. It feels like such a missed opportunity. I mean, if I were to make a list of the great missed opportunities in country music history, I might put that at number one.

EN: Well, thank you for entertaining even just the broad fantasy of what could have been. I think it’s super helpful to providing some context about Merle being more than just “Okie from Muskogee.” Let’s just talk really quickly about “The Fightin’ Side Of Me” as well. I actually like the song, even though it’s kind of fascist. I enjoy listening to it.

DC: Well, that’s how I feel. Like I say in the book, he wasted the best rhythm track of his life on that song. I loathe the lyrics, but the record itself really rocks. Funnily enough, “Fightin’ Side” was what I wanted to be the first single I ever purchased as a kid, but when I went to get it at Safeway it was sold out and so I bought Edward Starr’s “War” instead. “War” also really rocks but has a completely different meaning. So, yeah, I totally agree with you that it’s a great sounding record. And the live version that was cut and then played on some stations later is even fiercer. But it’s fierceness is to a really scary end.

EN: Before we depart completely from “Okie From Muskogee,” I wonder if you’d be willing to get a little remedial about the term “Okie” and what that meant in the Depression-era, when Merle’s family was one of the countless families to migrate from Oklahoma to California in search of a better life? It’s not a term of endearment.

DC: Quite the contrary. At that time it was a racial slur. Today I think Okie can be embraced as meaning, “I’m from Oklahoma and have working-class roots.” But “Okie” in the 1930s, didn’t just mean you were from Oklahoma, it meant you were “white trash,” a term that is at once a racial slur and a class slur.

EN: Interesting.

DC: “Okie” is a region- and era-specific variant of “white trash.” Now it’s always important to remember that Merle technically was not an “Okie from Muskogee.” He had never been to Muskogee, his parents never lived there either when they lived in Oklahoma, although they lived nearby. Merle had never been to Muskogee until he actually went and recorded the Live From Muskogee album. But he’d heard about it all of his life. He wasn’t from Muskogee and he wasn’t an Okie even in the mythic sense He’s not like the Joads, loading up the truck and heading out there for a new life because they were driven away by dust storms and droughts and insects and government policy.

Merle wasn’t part of that. He wasn’t born until his parents had lived in California for two years. But he most definitely grew up in a place and a time that looked down on Okies intensely, and saw them as an invasion of subhumans.

EN: That’s a painful piece of history I had not really understood.

DC: I would never want to try to pretend that any kind of oppression that white working-class folks have experienced is remotely as awful as what Black Americans have experienced. But Okie migrants and Black Californians at the time suffered adjacent hatreds. As Peter La Chapelle says in his excellent book about the Okie migration, there were theaters in Bakersfield with signs that instructed: “Negroes and Okies Upstairs.” Okies had to become white, as the expression goes, in the way that the Irish and the Italians had done previously. And they were able to do that, a potential that was itself a kind of white privilege.

EN: Merle’s trajectory is a really interesting evolution.

DC: Totally. After 9/11, I just happened to see him the Thursday after that Tuesday. The whole place was chanting “Fight! N! Side” that night before he even played a note. But he worked hard to make the occasion solemn rather than angry. Coincidentally, I interviewed him a couple of weeks later for a story that was in the now long-defunct magazine Country Music. When I interviewed him, I asked him about that show and that song, and he told me, “You know, right now our country needs to feel together. It needs to feel united. It does not need to be incited.” I think that’s a really important distinction. I think it’s a distinction he came to over the years and that maybe wouldn’t have been so apparent even to him back in the early ‘70s when he recorded “The Fightin’ Side Of Me.”

EN: Definitely.

DC: But he did come to it. It was a process. Later in his life he talked about how back during Viet Nam a lot of us were as dumb as a bag of rocks, including himself. And by the time you get to the Iraq war with George W. Bush, he is really against that war, and he loathes Bush for declaring “mission accomplished” when there was still so much war to go and so much dying. He hated it and he hated Bush.

EN: He was unequivocal.

DC: He stood up for the free speech rights of the Dixie Chicks, too, when they criticized Bush. And that was a risky stand to take in that moment when people were giving death threats to Natalie Maines and destroying Dixie Chicks records and kicking them off playlists. He stood up for their right to speak. Not many country acts did that. His attitudes evolved tremendously through the years.

EN: I want to talk about a few landmark Haggard songs in detail, non-“Okie” category, non-“Fighting Side” category. Let’s start with “If We Make It Through December.”

DC: That’s an absolutely amazing record. I don’t know if just the basics of the working class experience have ever been so accurately pinned down. The way it defines how even a holiday like Christmas is still subsumed by consumer culture. So to be unable to buy stuff for your kids because you’re out of work and to have to try to explain why you can’t do that to your kid — it’s heartbreaking and very real.

You know, I spend a lot of time in the book making the point that Merle is not as strictly an autobiographical songwriter as people tend to think he is. But when working on the second edition it finally hit me that “If We Make It Through December,” is actually very autobiographical. Because back in 1957, when he was getting drunk with a buddy and deciding spur-of-the-moment to go rob a café, it was right before Christmas. And then he and his buddy, and his wife at the time and his infant daughter, they all get in the car and they go to the tavern that Merle’s going to rob, because Christmas is coming and he’s sick of not having any money.

EN: Oh Jesus.

DC: And so anyway, it finally hit me that when he sings “And my little girl don’t understand

why Daddy can’t afford no Christmas…,” it really is his story. He leaves out the part about robbing the tavern so it can better tell our stories too. It’s a good example of the soundness of his instincts to universalize instead of making things purely out of personal experience.

EN: How about “Kern River”?

DC: In the book, I declare it one of the scariest songs I’ve ever heard. It’s so quiet, for one thing, eerily so. And it was a top 10 country hit in 1985. So in the middle of the Reagan administration, with all of that era’s inflated optimism, he released a song that is so circumscribed and trapped, from the point of view of a man who has lost the love of his life in a drowning accident. It’s not a prison song, but it feels like a prison the way that the valley, the river, the entire landscape where he lives is characterized as controlling him and watching his every move. It’s haunting.

EN: Yeah. Fantastic. I have one more for you: “Footlights.”

DC: Great song. “Footlights” is on the LP Serving 190 Proof which came out in 1979 and which many people regard as his best album. I would not argue. The album for certain marks a turn in his work towards more explicitly autobiographical songwriting, and “Footlights,” the opening track, is so autobiographical it couldn’t possibly be more autobiographical. It’s about the time he was told just before stepping on stage that his idol and friend Lefty Frizzell had died. He was devastated, had to go out and do a show when he didn’t want to go out and do a show.

EN: That’s terribly sad.

DC: At the same time, the song is about feeling alone and growing old. “I’m 41 years old and I ain’t got no place to go when the show’s over.” In some ways it’s just another road song like “Wanted Dead Or Alive” or “Turn the Page” or something, but with a critical difference. In most road songs like that there tends to be the payoff: but we do the show and we get the big response and it’s such a thrill! Nothing remotely like that happens in “Footlights.”

EN: Right.

DC: There’s no payoff. I think that’s one of the things that I really admire about Merle is the way he saw his job as a musician and an entertainer as just that: a job. It was work. And I see that in so many working class people I’ve known and lived with. That sense that you get up and go to work each day not for self-esteem or identity but just to pay the bills. And in Merle’s case, he’s doing it because he needs to be able to pay the band and crew who are depending upon him. And that’s it. Otherwise he doesn’t want to be there and would rather be fishing.

EN: I want to finish on a hypothetical. What do you think Merle would make of the current composition of our country and politics? Does this look more or less like the version of America that Merle might have hoped for?

DC: No. I don’t think it looks at all like what he might have hoped for. In his last decades his stances tended to line up with Democrats more than with Republicans, which people who only know him for “Okie” would probably not have expected of him. He defended the Dixie Chicks. He slammed Dubya relentlessly. He wrote a campaign song for Hillary Clinton, he wrote a celebratory poem about Obama’s victory in the 2008 election and before he died, during the primary season in 2016, he said he did not trust Trump. “I think he’s dealing from a strange deck.” That didn’t surprise me. He was always suspicious of wealth and power and privilege, and a guy who grew up in a converted boxcar was always going to be wary of someone with such a preposterously gaudy penthouse. At the same time, that doesn’t mean Haggard wouldn’t have ended up somewhere else, like millions of other white Americans who also hated Trump and then voted for him.

So we don’t know. What I do know is that I wish he were still around, still writing and singing. I’d like to hear the songs he would’ve written these last several years about the country he loved.