Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,159

This is the grave of Daniel Boone.

Born in 1734 in the Oley Valley of Pennsylvania, Boone was a boy of the 18th century frontier and that would never change, even as the 19th century came. His family’s farm was on the edge of white settlement, there were lots of Native people around, and Boone came to know them well. He became an expert hunter by the time he was a kid. His family were wayward Quakers, eventually expelled from the church because their kids kept getting non-Quaker girls pregnant and marrying outside the community. These were Boone’s older brothers, but what it meant for young Daniel is that he was indifferent to religion from here on and the family left for a new farm in western North Carolina.

When the Seven Years War started in North American colonies as the French and Indian War in 1754, the young Boone quickly joined the militia to fight against the French. He was just a private and while he was with Braddock during the disastrous attempt to defeat the French in the Ohio Valley, he was at the rear and did not fight. He returned home in 1756 and soon got married.

Boone stayed militarily active though. See, there was genocide to be had and plenty of Native people there to be killed. Tensions were very high between the British and Cherokee, as we have explored a lot in this series over the last few months, whether from the perspective of the genocidal whites in Tennessee or the Cherokee who had to deal with the aftermath. Well, Boone was part of this, even as a young man. The so-called Cherokee Uprising began in 1758 and continued until 1760 and the young Boone was very involved.

Boone was a fur trapper when he wasn’t committing genocide and it’s worth noting what an utterly disgusting job this was, having to cover yourself in beaver scent for the whole thing to work. People who were capable among living in society generally did not do a job such as this. This was for rough men and Daniel Boone was a rough man. He did have a family though. He was terrible at everything else and was constantly in debt and having to sell whatever he happened to own. So he constantly looked for the next chance, somewhere out on the frontier. That even could be Florida, which he traveled around in for awhile. He was captured by the Shawnees in 1769, had all his pelts confiscated, and told never to return. But he did return. Again and again.

Boone came to public attention when he figured out how to cross the Appalachian Mountains through Cumberland Gap and into Kentucky. This was 1775 and Boone led the way on Americans resisting one of the things they hated about the British–not allowing them to cross the crest of the mountains to commit genocide and steal the land and then have the mother country pay for the inevitable war. Soon, settlers poured into Kentucky and down into east Tennessee. The Wilderness Road was the product of the Transylvania Company paying Boone to find a way and make the speculators behind it a bunch of money.

At the same time, Boone wanted to fight the British-Native alliance against the colonists in the American Revolution. The tribes, who very much had a foreign policy, knew that with the British lie their only hope. In fact, Boone’s own daughter was kidnapped by the Shawnee and he pursued them and recovered them two days later. As the fear of red men engaging in sex with white women was central to the American taboo around interracial sex, this made Boone a popular hero. He was then captured himself by the Shawnee and managed to get along with them for quite awhile. When he was finally released, some locals wondered if he wasn’t a secret Shawnee agent since he didn’t seem to hate them. To show them that he was on their side, he immediately launched a raiding party against the Shawnee. No room for moderation on the frontier. Later in the Revolution, he split time between moving his family to Kentucky and being involved in local Virginia politics, which still owned Kentucky at the time. He was actually captured by the British trying to travel for Richmond for the legislature in 1781, but was released a few days later.

After the war, Boone tried to become a leading Kentucky citizen, but this really wasn’t his bag. He started a tavern on the Ohio River at Limestone, Kentucky. He did a variety of frontier-y jobs such as surveying. Popular writers wrote biographies of him that increased his fame. He saw military action one more time in another war against the Shawnee in 1786. By that year, he was able to afford slaves for the first time, the true sign of a rising figure in society. But the other frontier-y thing that Boone was all about was the ridiculous land speculation schemes that suckered in everyone who could afford to play, all the way up to George Washington. Most of these things were disasters and Boone wasn’t any more capable of playing this sharpers’ game than most other people interested in get-rich-quick schemes. He lost his shirt. In fact, by the 1790s, he was back to hunting and trapping to make money, despite being pretty old.

Finally, even though Kentucky named a county after him, Boone just left the U.S. for Spanish lands to try again. This placed him in modern Missouri in 1798. The Spanish were fine with this, happy anyone would be interested in moving there. He had land, but these were Spanish claims and the U.S. didn’t recognize them when it bought Louisiana from the French in 1803. So Boone lost his land again. In the end, he was just a hunter and trapper who was unable to succeed in any other way. He continued with this until he died, in 1820, at the age of 85. As late as the mid 1810s, he was exploring up the Missouri River

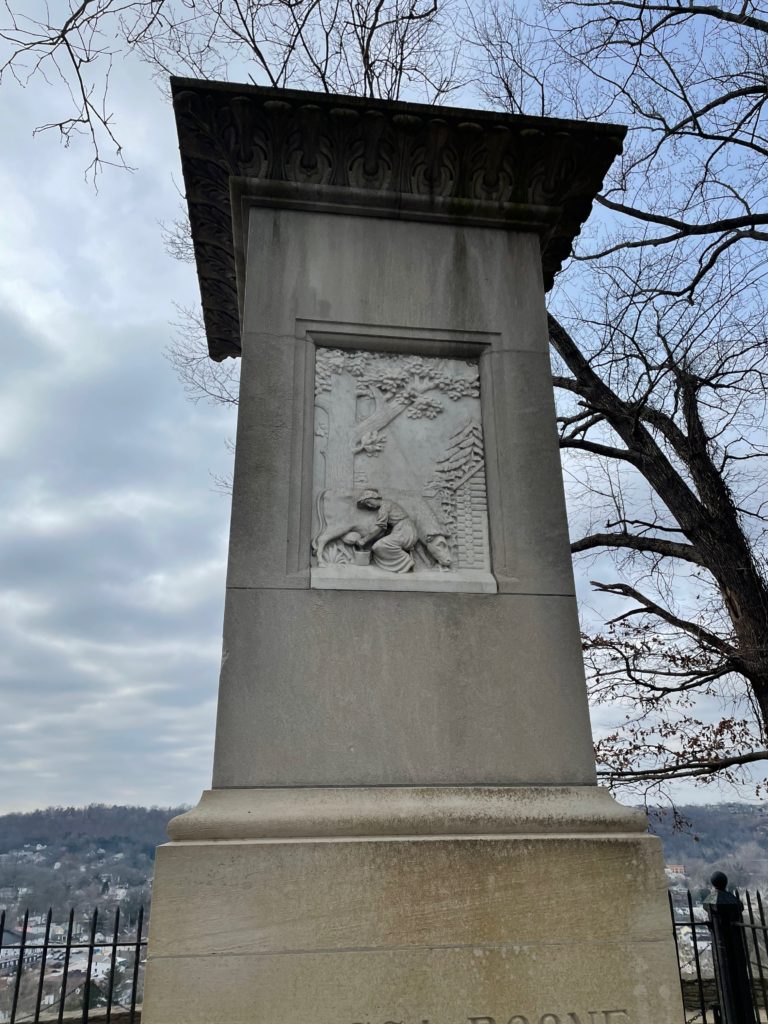

Sometimes, you might argue, as some have on occasion in comments, that my focus on genocide is a bit much. I don’t think so, but in the case of Boone, it’s literally emblazoned upon his grave as why he matters. This is how Kentucky chose to remember him. That’s why I took pictures of all four sides of the grave. The point of Boone is genocide. That’s why he was a hero. Killing Indians is what made him a hero, all the way until the mid-20th century when we were still making movies honoring this guy. Today, that would not be possible and I don’t think there’s much on people such as Boone and the fur traders and missionaries and others who were on the front lines of genocide in the 19th century West. We tell different stories today. But these stories are the ones conservatives want to bring back today. When genocide leads to “America the Greatest Country in History Even Though I’ve Never Been to Another Country Except That Time I Went to Cancun,” Boone is how you do it.

Daniel Boone is buried in Frankfort Cemetery, Frankfort, Kentucky. Or is he? Now, it’s actually unclear whether Boone is buried here. Some claim he is in Marthasville, Missouri. I am not particularly concerned with the details as I ain’t exactly digging people up in this series and running DNA testing to make sure. Who knows who’s buried under there? So we are running with it. How could I pass on a chance to highlight a grave that specifically identifies the person’s genocidal activities as heroic? In any case, the official story is that he was moved to this cemetery in 1845. So we will just go with it.

If you would like this series to visit other frontier whites, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Kit Carson is in Taos, New Mexico and Zebulon Pike is in Sackets Harbor, New York. Previous posts in this series are archived here.