Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,156

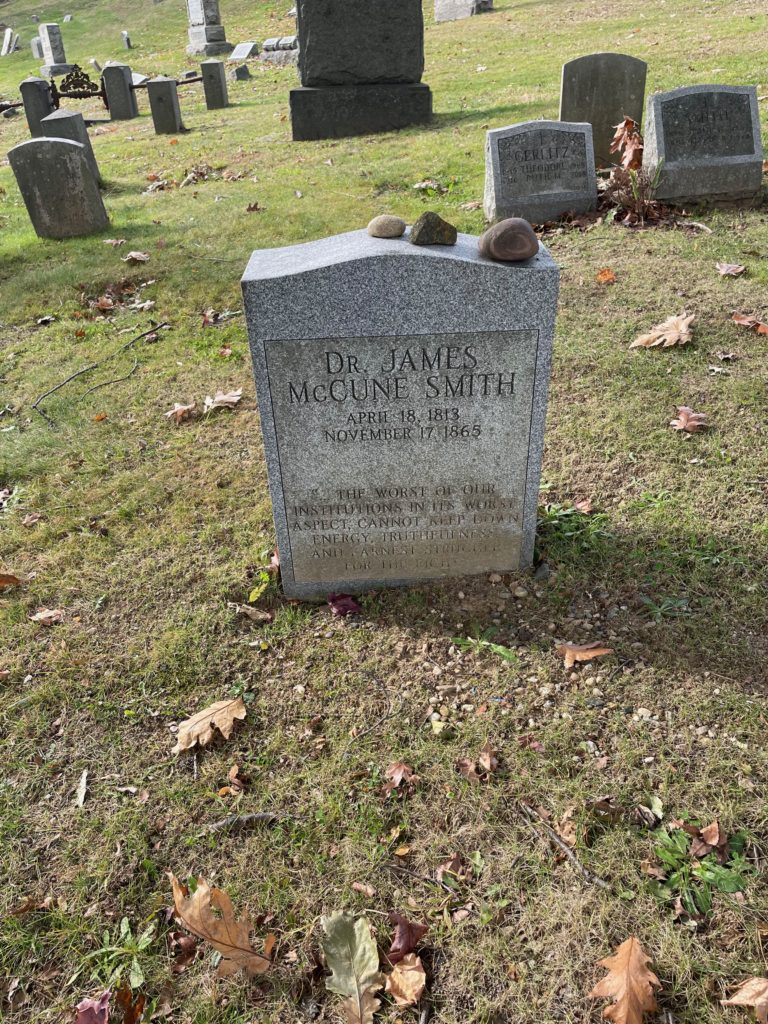

This is the grave of James McCune Smith.

Born in 1813 in Manhattan, Smith was a slave. Everyone forgets or just doesn’t know that New York was still a pretty significant slave state at that time. In fact, Smith would remain a slave until 1827, when the state finally emancipated all its remaining slaves. His owner was from South Carolina and had brought his mother up. It’s at least possible the owner was also his father. In any case, Smith managed to get schooling at the African Free School in Manhattan. He was a very good student and got connected in with the growing Black middle class of the city. He was encouraged to apply to Columbia for college, but was denied admission on the basis of race. So his mentors suggested the University of Glasgow instead. The African Free School had an endowment from rich white benefactors and they liked this idea so there he went.

Smith became a doctor, receiving three degrees at Glasgow to do so between 1835 and 1837. He went to Paris for further studies. Basically, he had the best possible medical training for the time. Now, medicine was still a pretty shaky field in the early nineteenth century, but still, he had the best there was of it. He loved Europe too, realizing that for the first time, he experienced real freedom. He probably could have stayed over there. It’s almost certain he thought about it. He knew he would face the overt discrimination when he returned home that he despised and hadn’t dealt with for awhile. In fact, the first time he tried to book a ticket back to New York, the captain refused to sail with him on the ship. But he did come back. He had to. The point of him getting that education was to serve the Black community in the U.S., and especially the growing free Black community in New York. So he finally made it back in 1837. He was seen as something of a hero among the benefactors for all his work.

Smith set up a practice in Manhattan that served Black New Yorkers. And he was tremendously successful. I mean, he was a rich man by 1860. He was a leader in the Black community and had done very well financially, so much so that he had a mansion built on Leonard Street. That mansion was built by white workmen and I think he enjoyed having whites do his bidding, though one might argue that he could have spread the wealth through his own community. He had an Irish servant as well.

One of Smith’s jobs was as the lead physician at the Colored Orphans Asylum. After the New York Draft Riots in 1863, when said Asylum was burned to the ground, Smith decamped from Manhattan and moved to Brooklyn, where he thought he would be safer from the racist Irish mobs. Over his life, he became the first Black doctor to have papers published in American medical journals and was the first Black doctor that well trained in the U.S. He maintained his position as the rebuilt Asylum though and overall worked there for 20 years. This was hard stuff. These were very poor kids with nothing and they had a lot of health problems. He did what he could, including giving the smallpox vaccinations. But how do you stop the tuberculosis? There wasn’t much he could do, even with his training.

Not surprisingly then, Smith was also hooked in with the leading abolitionists of the day. He got Gerrit Smith to give a bunch of land to serve as an endowment for the Asylum. He knew Frederick Douglass well. He also took a leadership role himself. One thing he despised was the American Colonization Society. This was the group, founded by Henry Clay among others, that wanted to free Black people and send them back to Africa. This was an openly racist movement predicated on the idea that the races could not live together. When New York considered a bill approving of the ACS, Smith led the charge to oppose it, gathering people to go to Albany and let the state government know in no uncertain terms that they were Americans and they had no intention of leaving their home nation. This was hard for whites to get into their head. Even as late as 1863, after the Emancipation Proclamation was in effect for months, Abraham Lincoln was seriously considering a colonization plan to send ex-slaves to Panama.

Smith also lectured frequently and his lectures about Black history, including Haiti, were popular. He helped organize New York’s resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act and was actively involved in the Underground Railroad. He and Douglass founded the National Council of Colored People in 1850 to promote educating Black children. He led a ten year campaign to fight segregation on New York’s public transportation. He edited The Colored American for a time. He led the charge to change the findings of the 1840 Census that freedom caused high levels of insanity among Black people (this was a John C. Calhoun forced thing) and John Quincy Adams built on that in the House to demand changes to the census, which Calhoun made sure did not happen. While some scientific organizations would not accept him because of his race, the American Geographical Society made Smith a member in 1854 and the New York Historical Society accepted him as well.

Smithi published a popular piece that took on Thomas Jefferson‘s racism in Notes on the State of Virginia, refuting the future president’s far too accepted scientific racism. Basically, Smith was a pioneer in noting that race was social, not biological. One thing we forget about the Enlightenment, because of our societal fetish for science, is that scientists ask questions that reflect their own biases and their findings thus often reflect that bias as well. It’s true today too. So people such as Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin took their new scientific method to decide the question “why are Black people inferior to white people.” The findings were in the question and this remained the central belief about race in western society at least through World War II, if not the present. Smith was a pioneer in rejecting this horror show and questioning the entire basis for asking such questions.

In 1863, Smith was hired to teach anthropology at Wilberforce College, the new Black college in Yellow Springs, Ohio. But he never got there. His heart was giving out. He died in 1865, just a couple of weeks before the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment, at the far too young age of 52.

In the end, like most social movements, we have reduced the mid 19th century Black abolitionist movement down to three people basically–Douglass, Tubman, and Sojourner Truth. All are worthy figures of course, but the reality was so much more rich than that. James McCune Smith is basically unknown today and that’s a real shame because he was the equal of all of them.

James McCune Smith is buried in Cypress Hills Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York.

If you would like this series to visit other leaders of the pre-Civil War Black community in the North, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. James Pennington, who was the first Black student at Yale, is in Jacksonville, Florida and William Cooper Nell, who was a close associate of Garrison and Douglass, is in Boston. Previous posts in this series are archived here.