Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,152

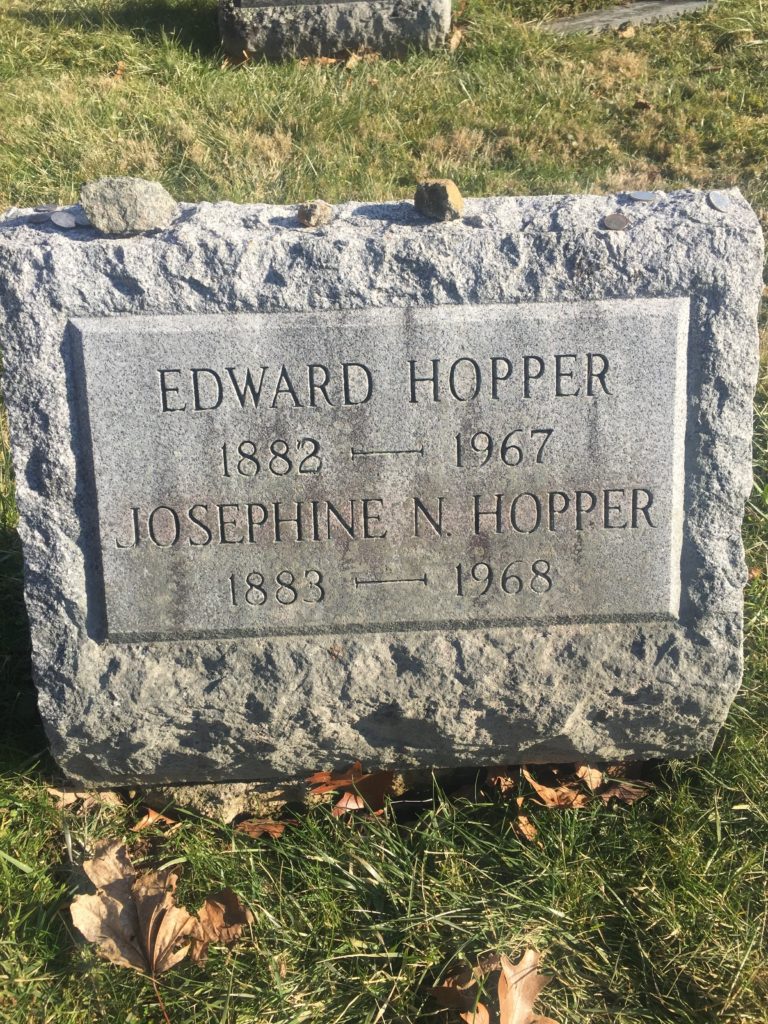

This is the grave of Edward Hopper.

Born in Nyack, New York in 1882, Hopper grew up in an upper-middle class family, the son of a dry-goods merchant. His father was something of a self-taught intellectual and young Edward was very interested in all this as well, immersing himself in French and Russian literature at a young age. He also became interested in drawing from a young age and his parents encouraged him in that. Good call! He started painting and soon was drawing self-portraits and all sorts of other things. Will it surprise you that the boy had a lot of talent? No, no it will not.

In 1899, Hopper began studying at the New York School of Art and Design. He worked there for six years, under the tutelage of, among others, William Merritt Chase, who was perhaps the most important American impressionist, and Robert Henri, who was among the most important realist painters of the era. But this was a shock to Hopper. It’s interesting in that he was raised in this intellectual environment but also his parents were very strict Baptists. Let’s just say that such things did not fly in art school. When he was exposed to nude models for the first time, he was….not ready for that. It was an adjustment for the conservative young artists. But he adjusted, at least to some extent.

By 1905. Hopper had to, you know, get a job of some kind. He wasn’t ready to make it in art yet. In fact, it would be some years before he could support himself this way. So he got a job in an advertising agency. He would work long enough to earn enough money to get him to Europe to study the latest developments in art, mostly in Paris, and then return to the U.S. But he still was unable to sell his own work for a long time. He was often depressed during these years, seeing no path forward, but unable to imagine giving up his art. Well, it’s a good thing he didn’t. He didn’t sell a single painting until he was included in the Armory Show in 1913, when he sold his 1911 painting Sailing to a businessman he knew for $250. But it was still a very hard slog from here. He now could sell something here and there but he mostly supported himself in the mid 1910s through making movie posters. Interestingly, while he hated this work, he was a huge movie fan and attended them all the time. His graphic skills came into effect in World War I, when he won an award for the most anti-German poster called “Smash the Hun.” Subtle!

Hopper worked hard though. Finally he started to sell a few paintings, got in a few more shows, but he was still a pretty minor artist in terms of public acceptance.

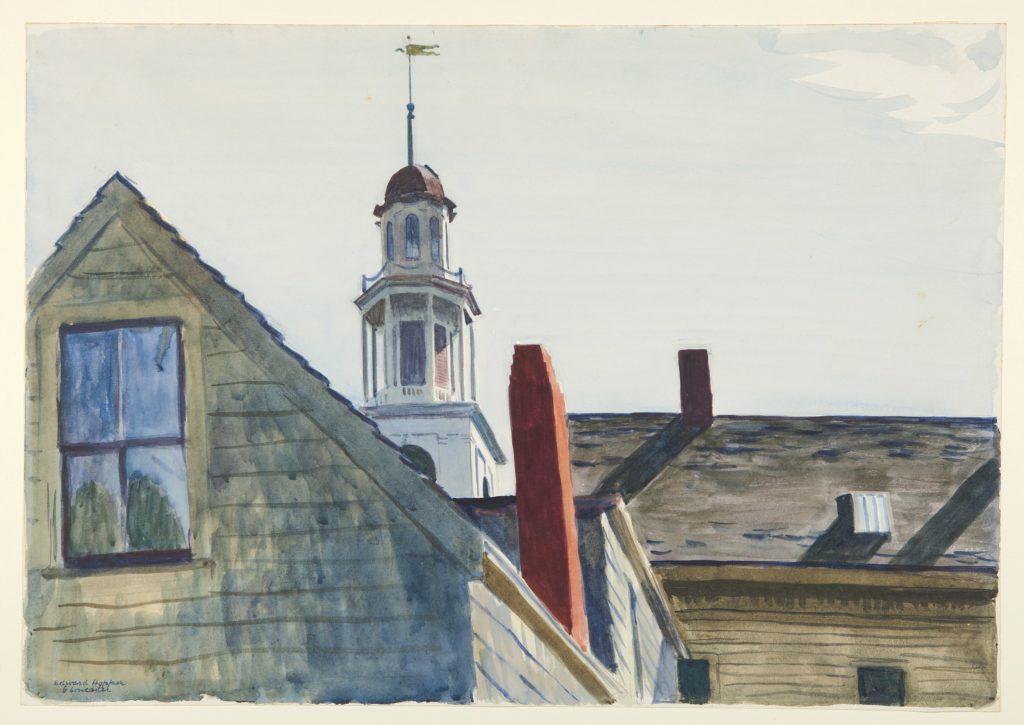

In 1924, Hopper married Josephine Nivison. Born in Manhattan to an artistic family in 1883, she also started drawing at a young age, went to what is today Hunter College to study art, and decided to make a go of it professionally. She had to teach school in order to make a living, but she kept painting. She also worked as an actress in the summer. She took a leave of absence to serve as a nurse in World War I, got there after the fighting ended, and came down with bronchitis before being sent home. Not so much of an adventure. She had met Hopper while they were both in art school. After some years, they met again and fell in love. They were at the same art colony in Gloucester, Massachusetts in 1923 and that’s how it happened.

Nivison would prove to be a huge influence on Hopper. For one, she was often his model for women. But also, she was brilliant in her own right and became a major intellectual influence upon him. She was also good for him generally. He was still the conservative Baptist who didn’t like to talk to people, while she was this very open, friendly human that everyone liked.

It wasn’t until Hopper married Nivison that his career took off. That is not coincidental. She recognized his genius and knew how to be the kind of person who could sell a painting. She basically took over the business aspect of his career. This started paying off pretty quickly. In 1927, he sold a painting called Two on the Aisle for $1500, allowing him to buy a car. Yes, at the age of 45, he was finally making enough money to live a middle-class lifestyle. After this though, things happened pretty quickly. The Museum of Modern Art soon recognized as someone they should be collecting. By 1931, the Whitney and the Met were paying thousands for his paintings. In 1932, he started showing at the Whitney Annual. Pretty quickly, Hopper and Nivison were rich. They rented a cottage on Cape Cod or a summer home in Vermont and he worked very hard through these years. Unfortunately, she ended her art career to support him. It’s a sadly typical story of a woman ending her career to support her husband’s. Moreover, he demanded this of her. Her painting made him uncomfortable and competitive. She acquiesced. Sigh.

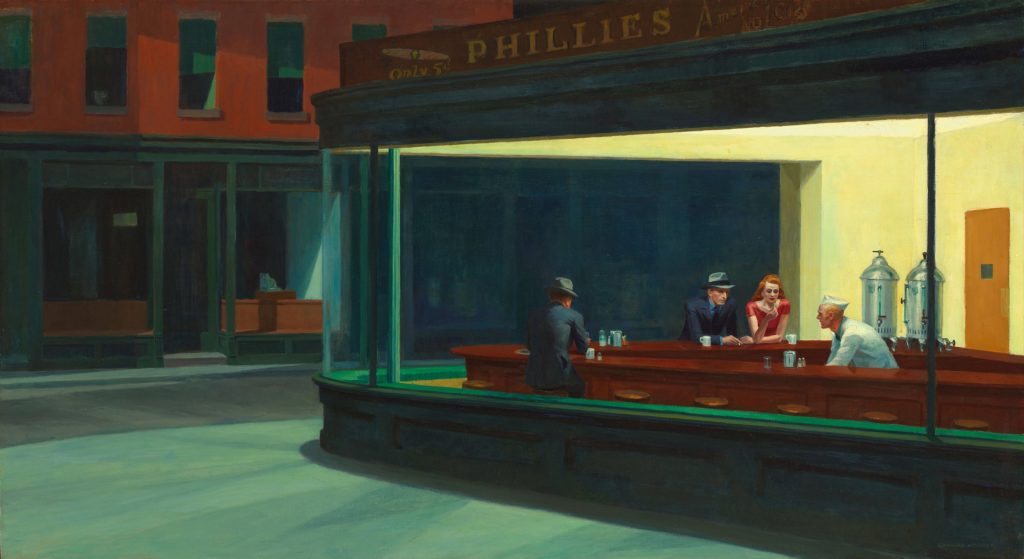

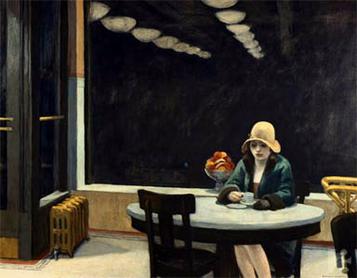

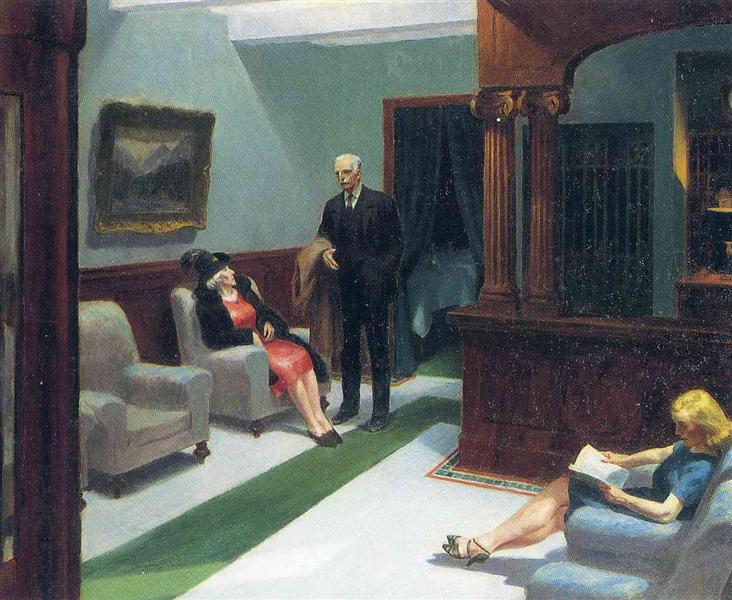

It was during the late 30s and 40s that Hopper produced many of his most classic works. These included New York Movie, Girlie Show, Nighthawks, Hotel Lobby, Morning in a City, and many others. These are among the most classic pieces of American art. Personally, while I like all Hopper, I, like many people, prefer his cityscapes than his landscapes. Some of this is that I find the coast kind of boring just in general (the beach sucks), but also I love the ambivalence in these city paintings. He doesn’t romanticize being in the city nor does he romanticize not being in the city. These are lonely people in his paintings. But whom among us is not lonely in the city from time to time. That contemplation, time off between interactions with the people, the deep longing of life, to me these are the major themes that I get from seeing Hopper’s work. Of course I’m not an art critic and really don’t read much art criticism, outside the occasional New York Review of Books essay. So what do I know. But it’s what I like about it.

Hopper did always remain the reticent conservative Baptist. He hated talking about his work, or really about much at all. He claimed there was no secret meanings to the work, that anyone could read it on the canvas so why ask me questions about what you can see with your own eyes. Of course, this has never stopped people talking about Hopper’s art. The amount of criticism on it and its influence on future artists is basically endless.

Hopper worked through the rest of his life. That ended in 1967, when he died in his New York studio. He was 84 years old. Jo Nivison Hopper died the next year. She was 84 years old.

In short, Hopper has a strong argument to be the greatest painter America has ever produced. Even if he forced his wife to end her career to make it happen.

Let’s look at some of Hopper’s work.

Edward Hopper and Jo Nivison Hopper are buried in Oak Hill Cemetery, Nyack, New York.

If you would like this series to visit other American realist painters, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Thomas Eakins is in Philadelphia and Childe Hassam is in East Hampton New York. Mary Cassatt is in Picardie, France, James McNeill Whistler is in London, and John Singer Sargent is in Surrey, England, you know, if you are feeling generous and all……Previous posts in this series are archived here.