This Day in Labor History: June 1, 1981

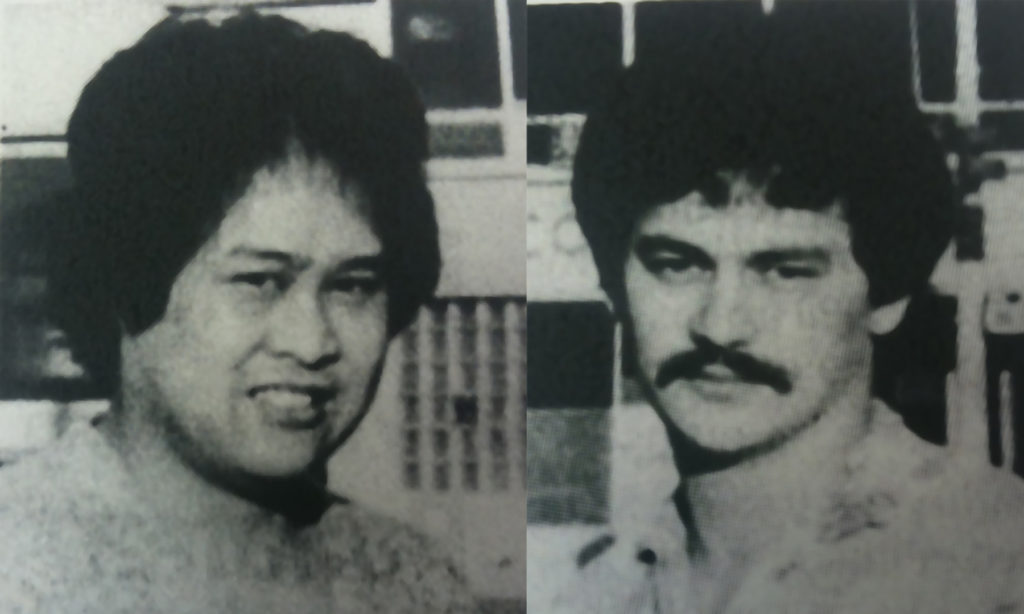

On June 1, 1981, Seattle-based Filipino nationalist and labor activists Gene Viernes and Silme Domingo were assassinated in office of Alaska Cannery Workers Local 27 (ILWU) on the orders of Ferdinand Marcos. This event shocked the Filipino community in the United States and helped lead to greater international pressure against the dictator in Manila. It also was a major blow to the cannery workers internal union struggle in an industry where exploitation of Filipino-Americans ran rampant.

Filipinos had played a significant role in American labor history going back to the early twentieth century. The imperialist conquest of the Philippines during the Spanish-American War and then the racist and incredibly brutal suppression of the Filipino independence by 1902 meant a new source of cheap Asian labor for west coast employers. With white workers demanding the West remain a white man’s country, the government had been forced to ban Chinese labor in 1882 and Japanese labor in 1907. But it was a lot harder to eliminate Filipino labor because they were technically Americans. Large numbers of Filipinos, mostly men, came to the U.S. in the 1920s to work in the fields. The outrage this caused in California, especially over Filipino men having sex with white women, led to major violence and finally the Tydings-McDuffie Act, giving the Philippines a path to independence in exchange for the immediate end of immigration. Yes, the United States proved too racist to be a colonial power.

The Filipinos who were here largely remained though. They would play a major role in the groundswell of farm organizing in California that eventually led to the United Farm Workers. Cesar Chavez would largely alienate the Filipinos by turning the UFW into a Chicano rights organization that sidelined their concerns and forced them into a subservient place in the union. Philip Vera Cruz’s memoir about organizing and the UFW is an excellent look into the problems with Chavez, which only got worse when for some reason he decided to meet with Ferdinand Marcos in a very poorly aimed attempt to repair relations with his Filipino members. Moreover, they were active in organizing the Alaskan fish cannery industry going back to the mid-1940s.

Both Gene Viernes and Silme Domingo were born in the United States. Viernes was born in Yakima, Washington in 1951 and Domingo in Killeen, Texas in 1952. Viernes was a grassroots activist who came up out of the fruit farms and canneries, following his father into that work when he was just a teen. Domingo’s father was a Filipino rights activist who fought in World War II and eventually moved his family to Seattle. His mother was an activist as well. Domingo became involved in the Filipino activist community in Seattle as a young man. At that time, there were significant divides between that community’s conservative elite, who often had ties to Ferdinand Marcos, and reformers influenced by Black Power and the other movements of the era. At the center of the rights campaign was the Alaska Cannery Workers’ Association. The fish canneries in Seattle were pretty heavily staffed with Filipino workers and they were treated horribly. Viernes was an activist within that organization. This was an internal union struggle. The ACWA was part of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union Local 37. While the ILWU was a union with a very democratic history, there wasn’t much real support for the cannery workers. There were still racial wages in the canneries that completely ignored the Civil Rights Act and other racial legislation. White, Native, and Filipino workers were housed in separate housing and paid different wages based on race. Meanwhile, back in Seattle, Domingo became a central figure in the Union of Democratic Filipinos (KDP in Tagalog) and founded the KDP chapter in Seattle. The KDP was overtly anti-Marcos and for a change in government at home and Filipino-American rights in the U.S.

One problem with the ILWU’s democratic unionism is that it could lead to the worst kind of democracy in unions. One was white supremacy. ILWU as an international was starkly anti-racist and union founder Harry Bridges abhorred racism. But he believed in union democracy more. So there were some locals such as in Oakland that were among the most anti-racist union locals in the nation, doing amazing solidarity work. But when the Portland local fought for white supremacy, Bridges refused to intervene and punish the local leadership. Another problem with a pure form of union democracy is that it can tolerate corruption as much as any other form of unionism. So long as the workers think the leadership represents their interest, well, that corruption can continue. In other words, sometimes it takes a strong hand from international leadership to crack down on bad behavior and that’s the one thing the ILWU didn’t have. So Local 37 was super corrupt and those pro-Marcos union leaders were making bank.

Viernes and Domingo, who was a member of the union as well through at least some cannery work over the years, decided to challenge the union leadership. They created a pro-democracy, anti-corruption platform. They were able to build on the networks of itinerant labor that Filipinos relied upon to win converts, not just in the Alaska canneries where organizing internally could get you in real trouble, but in the farms and fields they worked in the salmon offseason and which were not unionized. And they won. At that point, Ferdinand Marcos intervened. He and Imelda were close to those corrupt leaders. They knew that Viernes and Domingo could create a real challenge to their leadership in Seattle and in Alaska. In fact, earlier that year, Viernes had traveled to Manila to visit with labor leaders oppressed under the Marcos government and to give them a large check of money raised in the Filipino community to fight against the dictatorship. So they and the corrupt union leaders decided to assassinate the new leadership.

On June 1, 1981, Viernes and Domingo were in the Local 37 offices on Pioneer Square in Seattle. Pompeyo Benito Guloy and Jimmy Bulosan Ramil, Local 37 members and known gangsters, walked into the hall and shot the two men. Viernes died immediately but Domingo did not. There was a fire station next door and so they were there within two minutes. Domingo told them who shot him. He died the next day. Both were only 29 years old.

Now, originally, this was thought to just be an internal union struggle. The two murderers were given life in prison and connections were made to the head of the local Filipino gang. But supporters of Viernes and Domingo’s reform movement were not satisfied. They thought this very unlikely. They created the Committee for Justice for Domingo and Viernes and started searching for evidence. In doing so, they were taking their lives into their own hands. First, in 1989, a federal grand jury agreed that Marcos had ordered the murders and they found him guilty, not that it really mattered. Then in 1991, a jury convicted ousted Local 37 head Tony Baruso guilty of killing Viernes but not Domingo.

This is the 443rd post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.