How the Republican war on the administrative state will cook the planet

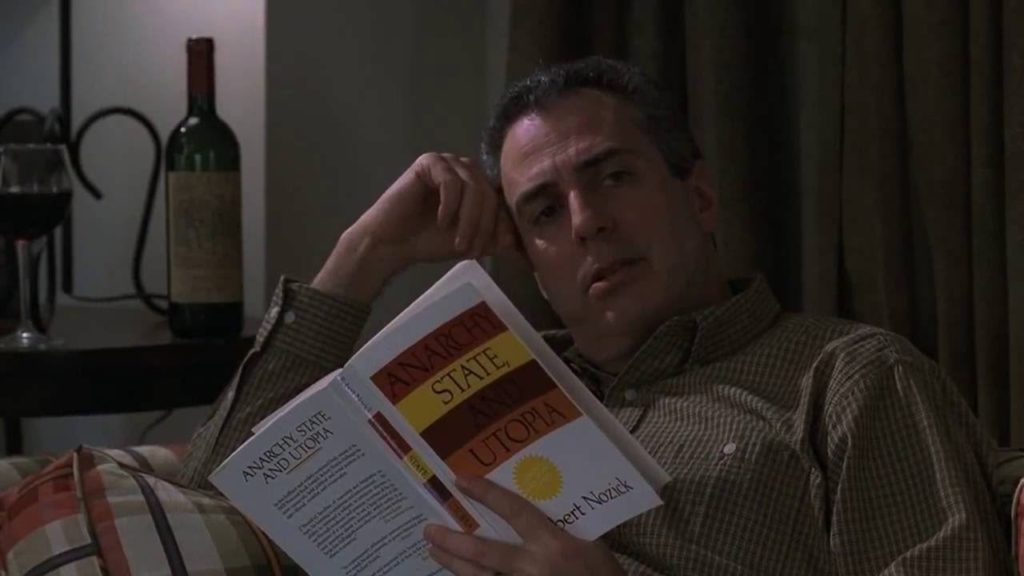

I especially like how this piece makes clear that the revival of “nondelegation” doctrine and the various other extratextual libertarian theories used to attack the administrative state are not serious legal arguments but the instrumental use of the courts by Republicans who think Democratic government is illegitimate:

Within days, the conservative majority on the Supreme Court is expected to hand down a decision that could severely limit the federal government’s authority to reduce carbon dioxide from power plants — pollution that is dangerously heating the planet.

But it’s only a start.

The case, West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency, is the product of a coordinated, multiyear strategy by Republican attorneys general, conservative legal activists and their funders, several with ties to the oil and coal industries, to use the judicial system to rewrite environmental law, weakening the executive branch’s ability to tackle global warming.

Coming up through the federal courts are more climate cases, some featuring novel legal arguments, each carefully selected for its potential to block the government’s ability to regulate industries and businesses that produce greenhouse gases.

Pretty much every word of Richard Posner’s critique of Scalia’s “textualism” is pure gold, but one crucial point is that requiring hyperspecific textual language before the executive branch can implement Congress’s policy choices is not a politically neutral approach but a deeply reactionary one:

It is true, as Scalia and Garner say, that statutory text is not inherently liberal or inherently conservative; it can be either, depending on who wrote it. Their premise is correct, but their conclusion does not follow: text as such may be politically neutral, but textualism is conservative.

A legislature is thwarted when a judge refuses to apply its handiwork to an unforeseen situation that is encompassed by the statute’s aim but is not a good fit with its text. Ignoring the limitations of foresight, and also the fact that a statute is a collective product that often leaves many questions of interpretation to be answered by the courts because the legislators cannot agree on the answers, the textual originalist demands that the legislature think through myriad hypothetical scenarios and provide for all of them explicitly rather than rely on courts to be sensible. In this way, textualism hobbles legislation—and thereby tilts toward “small government” and away from “big government,” which in modern America is a conservative preference.

The Gilded Age 2.0 is really not going to be fun.