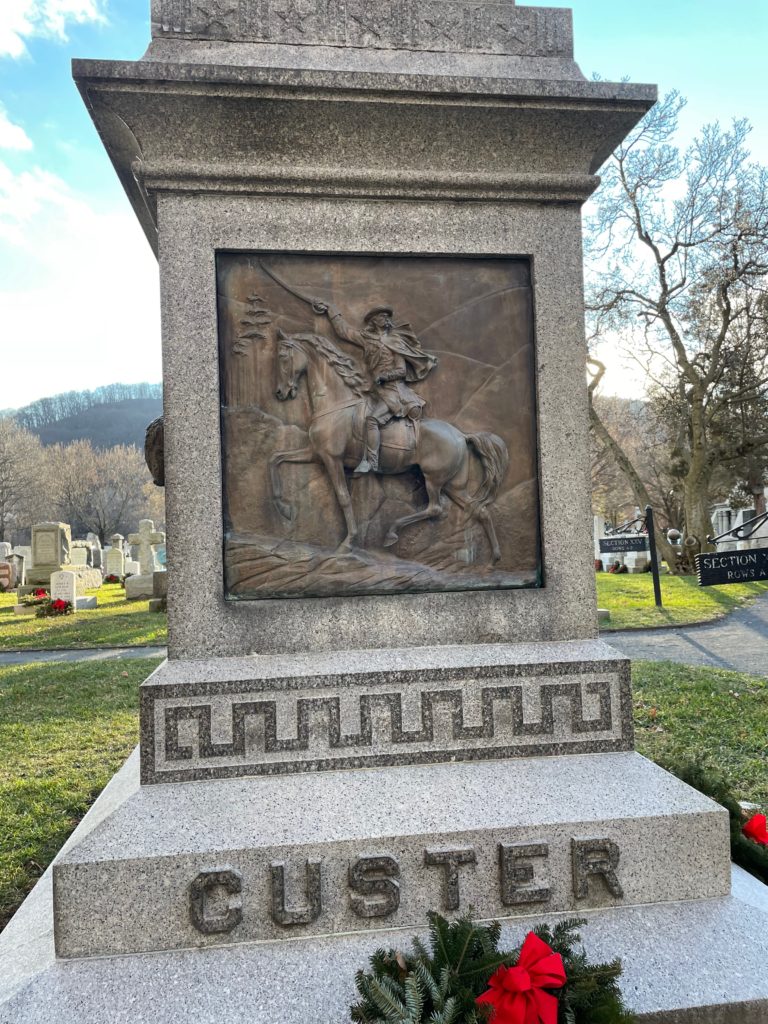

Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,128

This is the grave of George Armstrong Custer.

I always wondered when I’d get to this reprobate idiot genocidal murdering moron and now is the time, Christmas wreaths on the grave notwithstanding (I went out here in December).

Born in 1839 in New Rumley, Ohio….Ok wait a minute here. I drove through this place once and have also driven through other places in Ohio and Michigan Custer was associated with as a child. Endless statues and commemorations! Why!?!?!? What possible reason would there be to remember this moron even remotely positively. Well, it has a lot to do with the creation of the Custer memory, which we will get to here. In any case, Custer grew up in a Democratic Jackson-revering family where toughness and shooting and idiocy were taught as a matter of course. Custer moved to Monroe, Michigan for a better education, living with his older sister. The point was to get him to West Point. That succeeded, even if he was a horrible student. He started there in 1857, with the intent to graduate in 1862. He finished last in what remained of his class in 1861, sped up by one year and with much of the class leaving early to join the Union army or to commit treason in defense of slavery.

Being last didn’t chip into Custer’s already enormous ego and unearned self-confidence. He had set the all-time record for demerits at West Point and in a different time, he would have been banned to obscure post in the Northwest or something until he resigned, but this was the Civil War so he was sort of needed. By 1862, he was an aide to George McClellan and he initially performed well due to his careless attitude that sometimes could produce victory, as it did during the Peninsular Campaign when the 4th Michigan he led captured the first Confederate battle flag of the war. This got him promoted to captain and it reinforced his desire for publicity through daring behavior. Although he was briefly demoted to first lieutenant after another example of bad behavior, he was soon back on the rise. Custer was a consummate asskisser and if there’s anything a lot of these Civil War generals loved, it was to have underlings kiss their ass. So he became close to Alfred Pleasonton, a rising officer himself. Pleasonton was part of the officer corps seeking to replace the terrible political appointee generals that plagued the Union effort early in the war and as such, Custer rose along with him. Pleasonton, close to George Meade, wanted to find aggressive officers. Well, Custer was nothing if not aggressive. Custer became brigadier general of volunteers, which was great for him because they he could design his own outlandish, show off uniform.

Custer then played a major role at Gettysburg. He got there early on July 3 and led a charge against Stuart’s forces that cost them 257 casualties, highest of any Union cavalry brigade, but which also stopped J.E.B. Stuart‘s ability to join the Confederate assault on Missionary Ridge. Custer could have easily died that day, what with his ridiculous uniform, long hair, and carefree attitude making a really good target. But he did not die. He was promoted to a regular army position of major. Custer then was a major figure in Phil Sheridan‘s march through the Shenandoah Valley in 1864, burning everything they could to force the Confederates into submission. He was also at Appomattox Court House and Sheridan gave Custer the table where the famed surrender was signed, as a gift for his wife. So Custer was a big deal by this point. He was also still Custer. At the end of the war, he told his men to go steal a famous horse named Don Juan from its Confederate owner so he could ride it in the victory parade. They did, he rode it, then it freaked out and bolted in the middle of the parade. The Army told Custer to give it back. He did not.

Custer’s first postwar assignment was to head to Texas as part of the occupying forces of Reconstruction. His troops there despised him. Most of these people were used to the hard fighting of the near guerilla warfare in the West. Custer came in and tried to implement the discipline he demanded of his troops in Virginia. They totally revolted and upon being mustered out of the Army in November 1865, a number of them planned to ambush him and at the very least beat the hell out of him if not kill him, but someone informed Custer of the plot ahead of time and he got out of there.

But Custer’s role in the postwar Army wasn’t to administer Reconstruction, which he would have been horrible at anyway. It was to kill Indians. Now, he wasn’t sure he wanted to remain in the Army. He looked to make money. He thought about working for the railroads. He was so good at self-promotion that he was a fairly famous person at this point. Benito Juarez, presently fighting a war in Mexico against the occupying forces of the French-imposed Emperor Maximilian, offered Custer $10,000 in gold to join his army. Now that was talking for Custer. He applied for a leave from Army to take the position. General Grant was totally fine with this, but Edwin Stanton was not, opposed to the idea of American officers commanding foreign troops and the precedent this would set of American officers as foreign mercenaries. So the Secretary of War wisely axed that idea. Custer could have resigned entirely, but he didn’t want that.

It’s hard to overstate what a horrible genocidal bastard Custer was. Take the case of Black Kettle. The Cheyenne chief had survived perhaps the most disgusting genocidal massacre in American history (granted the competition is unbelievably stiff here) when he was somehow not killed by John Chivington and his army of racist scum at Sand Creek in 1864. But fast forward four years. Black Kettle and what was left of the Cheyenne were camping on the Washita River in what is today western Oklahoma. Custer ambushed the Cheyenne there, killed Black Kettle, killed a lot of women too, and shot all the horses he could find. In this, Custer fit the overall program of genocide endorsed by both William Tecumseh Sherman and Phil Sheridan, both of whom believing that the tactics used to force the South to surrender should be used against the tribes as well. Custer was cool with this, he thought killing indigenous people was good sport.

But it’s also worth a further explanation of the Washita River. First, Black Kettle’s band was at peace. You think Custer cared about that? Ha ha, no way. They were Indians and deserved death. This was hardly something that Sherman and Sheridan disagreed with and there were lots of cases of massacres against innocent encampments during these years, something assisted by said innocent encampments being easy to target since they didn’t feel they needed to be on the run. I mean, the Cheyenne weren’t even at war with the U.S. at this time! Second, Custer had really gotten himself into trouble before this. In 1867, during Winfield Scott Hancock’s campaign against the Cheyenne, by which time Custer was a lieutenant colonel in the recently created 7th Calvary, a search party under Custer was massacred. But Custer was nowhere to be found. He had gone AWOL to see his wife, evidently thinking he could do whatever he wanted, the long theme of his career. This nearly ended Custer’s career. He was arrested and held at Fort Leavenworth. But remember that Custer had friends. If he had one thing, it was friends. Phil Sheridan personally intervened and he only got a one-year suspension from duty. It was shortly after that suspension had ended that he murdered Black Kettle and his people. It was almost as if Custer had blamed the Cheyenne for his suspension and he determined to get his revenge. But in any case, Army brass had no real problems with his actions at the Washita River. After all, it did what they ultimately wanted, even if it wasn’t quite how they would have done it.

Custer was kind of bored there for a few years after that. He didn’t get to do enough killing. That drought ended in 1873, when he was sent to Dakota Territory to protect a railroad crew. There was a skirmish with the Lakota, understandably angry about this new invasion to their territory, some shots were fired, one soldier and one Lakota were killed. This gave Custer the edge. He personally invaded the Black Hills the next year, heard there was gold there, discovered it was true, and announced it to the public. The Black Hills gold rush was the death knell of Lakota control over their lands. It was also an act of pure genocide. Custer knew what would happen. This is what he wanted. Of course Custer became a hero to the people who invaded Lakota territory illegally. The town of Custer was named for him due to this. While this all caused some legal wrangling, it wasn’t as if the people above Custer in the American government exactly opposed his actions and they were going to bring the Black Hills under U.S. control, especially with the valuable gold.

But all this did cause a lot of problems. The Grant administration was less pro-genocide than Sheridan and Sherman (much to the frustration of these two men that Grant had brought with him through the Civil War). So Grant tried to coax the Lakota to sell the land to the government in 1875. The Lakota weren’t having it. This was their sacred space and if you want to point out that they had only been there for a 100 years or so as part of the general movement of the tribes responded to the push from the east from Europeans, well, that may be true but it doesn’t make their claims to it any less legitimate.

So Custer was finally tasked with bringing the Lakota onto a reservation in 1876. But just before he was supposed to do this, he was called to Washington to testify about the ridiculous level of corruption in the Grant administration’s running of the reservations, around Secretary of the War William Belknap, the contracts for supplies, and Grant’s own brother who was making a lot of money on all this. Custer was furious. He wanted to fight. He had waited for years to kill a bunch more Indians. He resisted testifying. But when he finally had to, he had a bit of revenge by accusing Grant’s brother of extortion. He didn’t really have any evidence here. The president was absolutely furious and wanted Custer removed from the command of his troops in the upcoming war. Again, this is where Custer’s endless ass kissing came to his aid again, as Sherman tried to negotiate a compromise where Custer would apologize to Grant. But the president wouldn’t accept Custer’s messages. So finally Custer just left Washington and headed back to the Dakotas against Grant’s orders. Grant ordered his arrest. Sheridan had no choice but to do this, as much as he didn’t want to. But Custer was so good at self-promotion that the story soon got out and the newspaper coverage was extremely favorable to the general, condemning Grant in harsh terms and reminding everyone of the massive corruption that plagued his administration. Grant finally caved, much against his will. That’s only because he was afraid that without Custer’s leadership, the campaign against the Lakota would fail, which is what Custer’s commander Alfred Terry also feared. Terry, Sherman, and Sheridan all worked on Grant and the president relented. Ah, the joys of the Gilded Age.

And…..that leads us to the Little Bighorn. We don’t need too much detail here. Custer was an idiot and for once he paid for it with his life. It should have happened earlier, for both moral and strategic reasons. He walked right into an enormous encampment of Lakota and their allies the Cheyenne and Arapaho. Custer only had about 300 soldiers total and Sitting Bull had up to 3,000 or even 3,500 warriors. By all accounts, Custer’s actions were disastrous the entire way, from his strategy to his overconfidence. The entire regiment was wiped out, each and every soldier. Remember now that Custer was famous. So his death was in the headlines even more than it would have been with a regular officer. The flamboyance, the recent political intrigue, the self-promotion–all of this led to great copy. But nothing led to better copy than his death. Of course, none of this really changed the tide of the war and Sitting Bull was forced to flee to Canada and the Dakota wars were basically over by 1877 as other, less incompetent and less stupid generals finished the job against the utterly overwhelmed and starving tribes.

Custer might have died and if not forgotten over time, at least consigned to more or less a footnote in American history. After all, it’s not like he really did anything that significant here except to die in the stupidest way possible. There were lots of genocidal generals and lots of key players at Gettysburg who aren’t generally known today. But that did not happen. Everyone knows Custer. This is mostly because of his wife Libbie, who is also buried here and was a remarkable woman in some ways. She was only 34 years old when Custer died. She had often opposed his crazy actions, such as the Mexican plan after the Civil War. She had grown up wealthy and had strong opinions. Their marriage was pretty difficult. Neither was particularly easy to deal with. But in the end, she was totally committed to him. When he died, a lot of the media noted that he was an idiot who got what he deserved, which was true. But she spent the rest of her long life devoted to his memory and making him a hero to the public. It didn’t hurt that the end of the Indian Wars brought a massive of nostalgia immediately after his death, to the point that Sitting Bull would spend his time in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show reenacting the Little Bighorn for a little money, meat, and tobacco. Americans ate this up. So sure, Custer was dead, but why not make him a hero for a more fun time? Cody made a killing.

Libbie Custer was a critical figure in making this happen. She published three books about her life in the West with her husband: Boots and Saddles in 1885, Tenting on the Plains in 1887, and Following the Guidon in 1890. All were huge sellers. They were generally considered fairly accurate discussions of her husband, the West, and the Army, though obviously not objective at all and dedicated entirely to making the American public think of her dead husband as one of the nation’s great heroes. She traveled around giving lectures about her husband and the West. This all also made her rich. Custer had a lot of debts and she had trouble settling them. He certainly didn’t leave her with much. But she lived a pretty elite life after this. She also refused to remarry, even though she was a young, attractive woman who had plenty of offers. She died in 1933, at the age of 90, having fulfilled her life’s dream of making her husband a national hero, against all the facts.

George Armstrong Custer and Libbie Custer are buried in United States Military Academy Post Cemetery, West Point, New York.

If you would like this series to visit other military officers involved in the genocide in the American West, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Frederick Benteen is in Arlington and William Tecumseh Sherman is in St. Louis. Previous posts in this series are archived here.