This Day in Labor History: May 12, 1959

On April 12, 1959, unions led by the International Hod Carriers’, Building, and Common Laborers’ Union of America and with assistance from the United Steelworkers of America and the Operating Engineers, filed for an election with the National Labor Relations Board at a mine in Medicine Hat, Utah. This obscure moment is a date in which we can talk about the complex relationships between organized labor and tribal governments.

The Four Corners area is one that is largely controlled by the Navajo and Utes, while a few towns exist on the outskirts of the reservations, such as Gallup, New Mexico. This is all mineral-rich country. So miners came to these regions and the white and Mexican ones at least, living in towns such as Gallup, formed unions. In 1933, there was a significant strike with the National Miners Union. This strike was conditioned in part by white resentment toward Native workers, who lived on the reservations and thus did not have to pay rent for housing. The strike was crushed but those tensions remained. And even when these mines unionized with the United Mine Workers of America in the 1940s, the cultural and political differences between the Navajos and other miners were quite great and difficult to overcome.

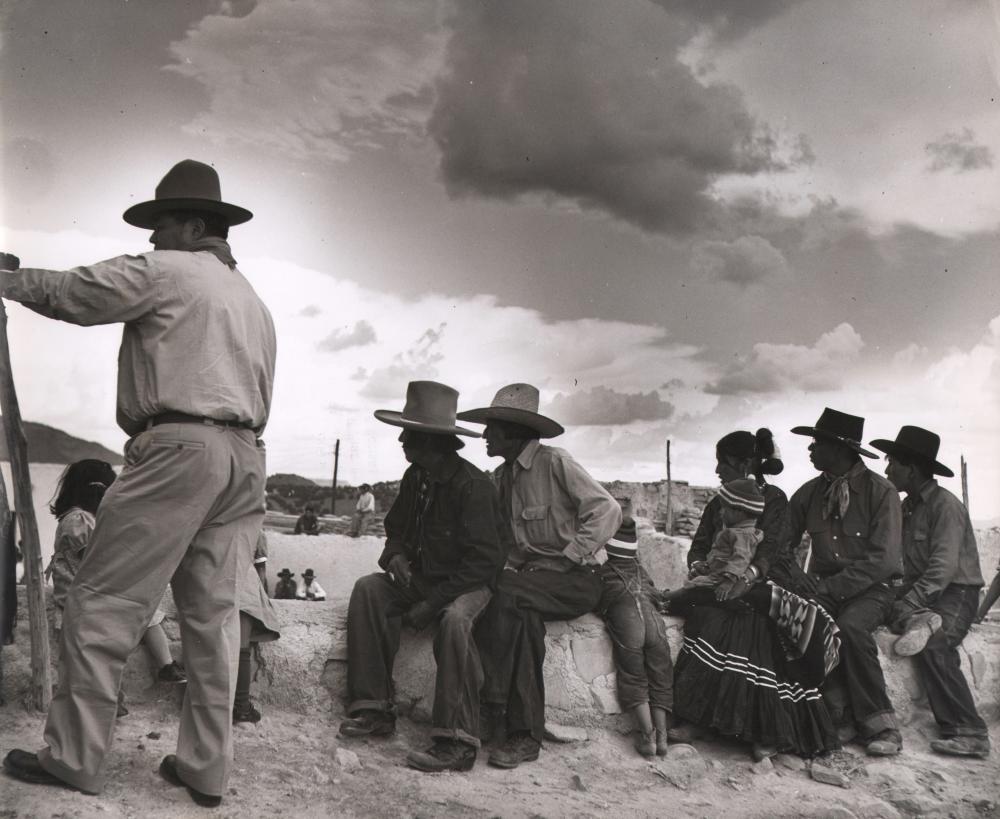

Relationships between the white miners and the Navajos continued to be not good by the late 50s. Racism was super common as was racial violence. In one 1958 story, miners lured three Navajo guys to the local fire station, covered them with paint, and beat them up. Another major mining center was in Medicine Hat, Utah, northwest of the Navajo nation. But there was work and unions wanted to organize workers regardless of race. Plus, as we know now, unions are the best organization to fight against white racism among the working class. One of the unions involved in this area was the International Hod Carriers’, Building, and Common Laborers’ Union of America. They had to work pretty hard to get Navajo interest. This mostly white union had mostly white characteristics. Navajos spoke and related in a different way. An organizer going in and giving a speech didn’t necessarily work on the reservation. In fact, it might turn off people who thought he just didn’t understand them. And he didn’t in fact understand them. Organizers assumed class identities and proper class-based behaviors that were not appropriate in Navajo culture. The first rule of organizing is to meet people where they are at, but if you don’t known Navajos, how can you do that?

After several failures, the Hod Carriers decided to try again to organize the region in 1959. The Navajo Tribal Council strongly opposed this union effort. For Navajo leaders, unions were an outside element that had nothing to do with tribal culture. Moreover, Navajo leaders were developmentalist in their own way and largely wanted to side with employers. In 1958, it had already passed a law banning trade unions on the reservation, which wasn’t really legally enforceable. When the union campaign started, it argued that the National Labor Relations Board had no jurisdiction on Navajo land. This was a pretty sketchy legal argument. Had it been a state-led commission of some kind, then sure. But there was clear precedent for federal agencies to supersede tribal law. But the tribal council took it into the courts. In 1960, the courts rejected the Navajos arguments, stating that the NLRB in fact did have jurisdiction and that the relevant mining company engaged in interstate commerce. But the Council was not through. It appealed to the U.S. District Court, which backed up the NLRB and stated that the 1868 treaty granting the Navajo its reservation had nothing in it about labor relations.

This hardly stopped the Tribal Council from working with employers to bust unions. It attempted to enforce its anti-union law. It told Navajo workers at Texas-Zinc that if they joined the union, they would be arrested and get six months of hard labor!!! They also banned white union representatives from having access to the reservation. Representatives from various unions were rounded up and forcibly evicted from reservation land. The Steelworkers saw that this campaign was doomed to failure and pulled out. The Hod Carriers and Operating Engineers carried on. But the vote in 1961 was against unionization by an overwhelming 56-11. The short version is that white unions simply had no clue on how to operate with Native people. For the Navajo workers who were interested in unionization, they had to face a choice of going with the ways of their own racial leadership or with the white man. And given the horrors whites had inflicted on Navajos for a century by this time, why would they choose the latter? This also played into the hands of developmentalist tribal leadership. By defeating the Hod Carriers and Operating Engineers, they could both promote racial pride in standing up to white Americans and attract outside corporate investment.

It’s true enough that for however dismaying this history might be for those of us who support unionization, unions did do a better job by the mid-60s in figuring out how to work with Navajos. Like a lot of our labor history, a big piece of this was the election of Raymond Nakai to head the Navajo Tribal Council in 1963. Nakai was more liberal and more interested in working people than the previous administration. Nakai also started working with the AFL-CIO to promote Navajo hiring in the building trades and other unionized jobs in nearby towns. This led to a significant increase in Navajo trade union membership. In 1950, there were maybe 50 Navajos living on the reservation who were union members. By 1977, there were 6,000. There was still tensions, largely because white unionists still struggled to understand Navajo culture and because last-hired, first-fired policies really tended to hurt Native workers disproportionately. Moreover, Navajo workers did not fit into white workplaces easily. For example, Navajo workers in the 70s demanded time off to deal with family obligation and to take care of sheep herds. To say the least, neither corporate America nor the AFL-CIO had any idea how to handle a situation like this. On both fronts, it became easier to just hire white workers.

This post borrowed from Colleen O’Neill’s Working the Navajo Way: Labor and Culture in the Twentieth Century, which is an outstanding discussion of Native Americans and labor history, an understudied issue. Check it out.

This is the 439th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.