Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,108

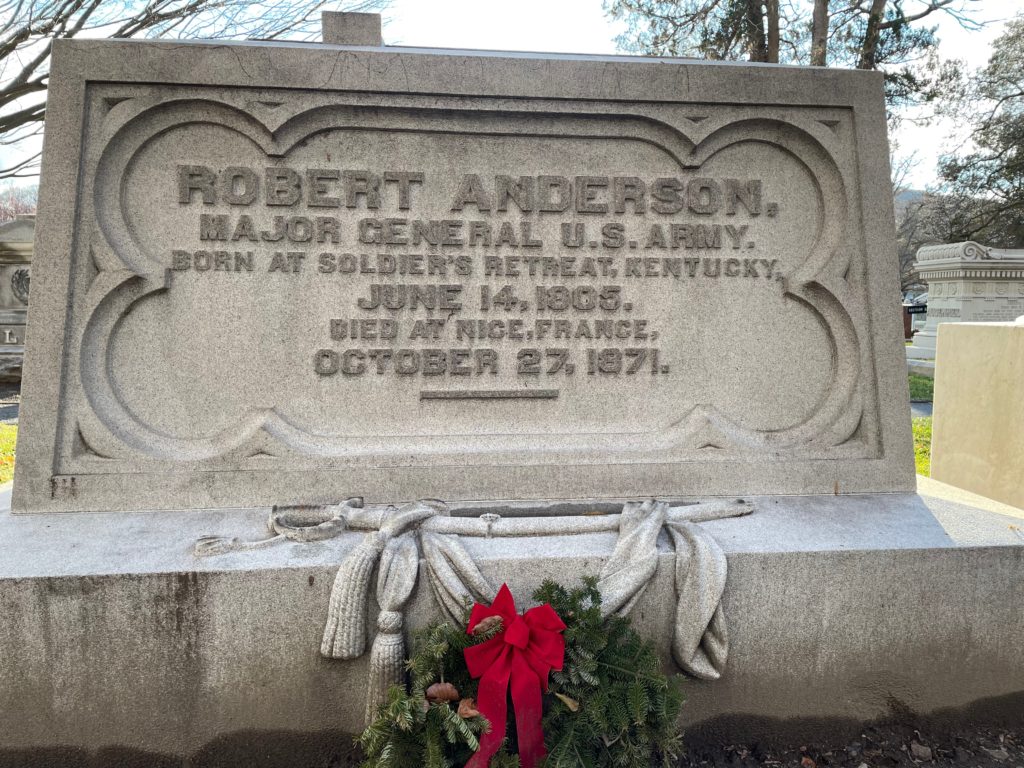

This is the grave of Robert Anderson.

Born in 1805 near Louisville, Anderson was destined for a career in the military. His father, Richard Anderson, was the Marquis de Lafayette’s aide-de-camp during the American Revolution and was a founding member of the Society of the Cincinnati. Meanwhile, his mother was John Marshall’s cousin. Not only was his father a leading military figure, but the family plantation was called Soldier’s Retreat. So it’s not surprising that young Anderson was headed to West Point, where he graduated in 1825.

Life in the early 19th century Army mostly meant genocide. And that was true for Anderson as well, who was quite active in the Black Hawk War and the Second Seminole War. However, before that, his first commission was to serve as the private secretary to his older brother, who was minister to Gran Colombia, the initial Bolivarian attempt to unite much of South America in one country. But his role in the Black Hawk War was very real, including being in charge of taking the prisoner Black Hawk after his surrender in that sad war. He also engaged in military strategy and theory, writing Instruction for Field Artillery, Horse and Foot, in 1839.

During the Mexican War, when the United States decided to steal half of Mexico to expand slavery in an unjust and imperialist war, Anderson was heavily involved as an officer in battle. He was in the Siege of Veracruz, the Battle of Cerro Gordo, and the Battle of Molino Rey. At the latter, he was severely wounded and nearly died during an assault. It took him about a year to recover from his wounds. After the war and upon his return to active duty, he was the commander of Fort Preble in Maine. He did that for much of the next several years, outside of a stint in Washington when he worked with a group of officers on something called “A Complete System of Instruction for Siege, Garrison, Seacoast, and Mountain Artillery.”

By 1855, Anderson, who never fully recovered from his wounds in Mexico, was not in great health. But he also wanted to remain an active officer. He was also close to Winfield Scott, which meant he got assigned super light duty. I mean, super duper light. His role, as a senior office, was to inspect iron beams the iron contracted out at a New Jersey factory. During this period, he received a promotion to major as well. Must have been pretty good at the beam inspections. I kid though, he was a serious officer.

By the end of 1860, someone like Anderson needed to be doing real work. The South was committing treason in defense of slavery. What would happen to the southern forts? Thus, Scott assigned Anderson to be the new commander at Fort Moultrie and Fort Sumter, off the coast of Charleston, South Carolina. Now, Anderson’s family was a slaveholding one. I don’t know when he stopped owning slaves, but he definitely had owned that at some point. After all, these were Kentucky planters with elite Virginia roots. But like lots of people who were sympathetic with the idea of slavery, Anderson found talk of disunion disgusting. He was based at Fort Moultrie, but believed in indefensible in the event of an attack. So he moved his operations to Fort Sumter. I hardly need to tell you the rest. When Abraham Lincoln chose to resupply the fort in 1861, the Confederates opened fire and this was the first action of the Civil War. Anderson returned fire but was totally overwhelmed. He surrendered the fort a day later. Luckily, no one was killed in the bombardment. There’s really nothing he could have done.

Naturally, this is the only reason we remember Anderson today, who was by all counts a competent officer but not much more than that. But with the Civil War getting under way. Anderson became the first national hero of the war. That meant he had a lot more value working to build up war support than whatever he could do in the field. He got a promotion to brigadier general right after the surrender. He led a parade in New York’s Union Square to support the war. Interestingly, at least according to some writers, it was at this parade and around the figure of Anderson where the American flag began to take on its modern patriotic meaning. This is new information to me and I had never even thought about the question before, so I can’t really evaluate the claims.

After this parade and a tour of the North, Anderson was given a quite sensitive role as the head of the Department of Kentucky. The reason for this complexity is that Kentucky had taken on the completely ridiculous position that it was “neutral” in the war, as if this was sustainable. Now, it turned out it would be the Confederates who first violated that neutrality and moved the state toward the Union, at least until 1866 when the state memory began to venerate the Confederacy. Anderson’s job was to prepare the state’s forces for war on the Union side. But he was reluctant to do this. Lincoln ordered him to give out rifles to state unionists. Anderson thought this was a violation of the neutrality. So Lincoln fired him and gave the job to William Tecumseh Sherman, beginning his rise as a trusted Lincoln general.

After that, Anderson was given a pretty meaningless post as commander of Fort Adams in Newport, Rhode Island, which today is far more famous as the site of the Newport Folk Festival and Newport Jazz Festival. He retired from active duty in 1863, his long-term injuries just getting too much for him to bear in active duty. However, he remained on staff in New York until 1869. At the end of the war, the military gave him a promotion to major general for his work at Fort Sumter, which wasn’t really deserved, but he was now such a symbol of the war as it was ending with a hard-fought victory. When the war ended, Anderson returned to Charleston to raise the U.S. flag over Fort Sumter. That must have felt good.

At the end of his life, Anderson sold his substantial library to pay for a long trip to Europe. Some of this was to find better treatment for his physical aliments, but I think he also just wanted to see Europe before he died. He died in Nice in 1871, at the age of 66.

Robert Anderson is buried in United States Military Academy Post Cemetery, West Point, New York.

If you would like this series to visit other Civil War generals, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. William Tecumseh Sherman is in St. Louis and Henry Halleck is in The Bronx. Previous posts in this series are archived here.