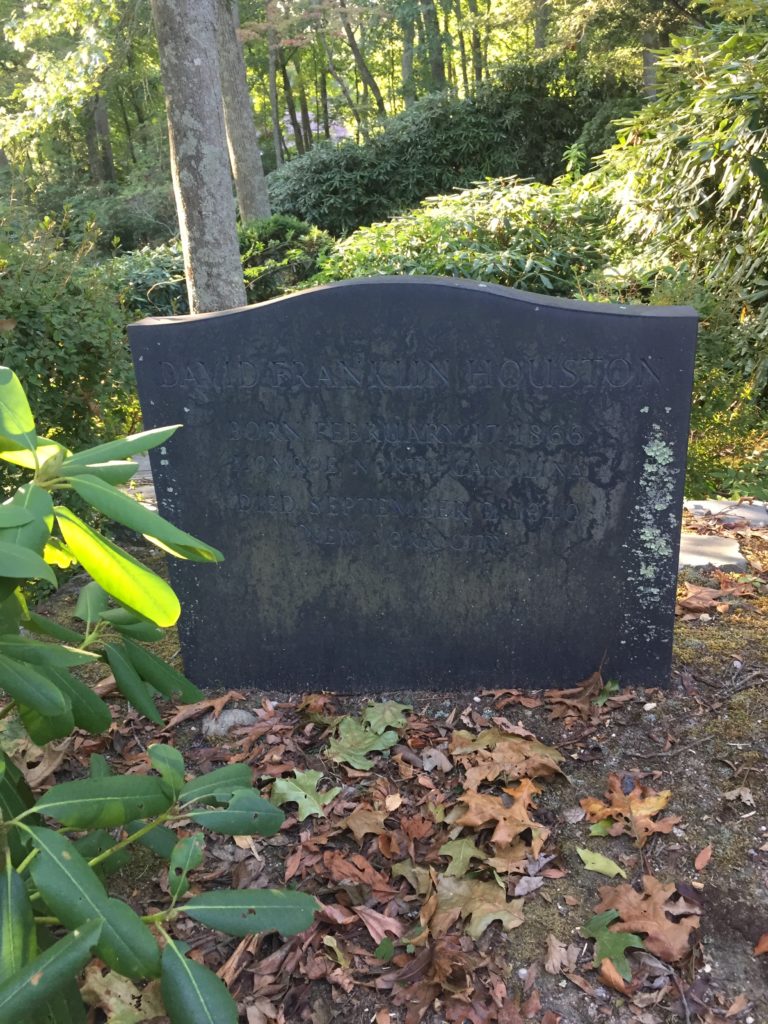

Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,103

This is the grave of David Houston.

Born in Monroe, North Carolina in 1866, Houston grew up in middling circumstances. His father was a horse dealer who also ran a grocery. What Houston definitely was brought up in was the white supremacy of the time. This was a place and time with a great deal of white bitterness toward the Civil War and Reconstruction. Houston would share this. He developed very conservative politics, of course based in the Democratic Party.

Houston was able to attend the University of South Carolina, graduating in 1887. He then went to Harvard for graduate work in political science. He made his academic reputation writing a book about the nullification crisis in South Carolina, which I am pretty sure is terrible and racist. He got a job at the University of Texas, where he became the dean of the faculty in 1899. In 1902, Houston was named president of what is today Texas A&M University. He then went back to Austin to be president of Texas in 1905. Three years later, he was off again, this time to Washington University in St. Louis, where he stayed for five years. Moreover, he was a rising star in the American power structure. He opened a lot of new schools within these universities and made connections with big-time politicians. Thus, William McKinley named Houston to the board of visitors at West Point, which was largely a ceremonial thing but still, Houston was the kind of guy to get these positions.

Far more significantly, Houston was close to Woodrow Wilson, another conservative southerner political scientist who had risen in academia. Houston had gotten to know Wilson’s close advisor Edward House and it was House who introduced the two when Wilson was governor of New Jersey. So when Wilson became president in 1913, he named Houston Secretary of Agriculture. It wasn’t an unreasonable choice, especially given his Texas connections. A&M especially was an agricultural institution. And he did know how to administer a reasonably large organization.

Houston was a reasonably important person in a position that is largely forgotten when we think about administrations. This was an era of significant agricultural reform that Houston had to oversee. The Smith-Lever Act created the modern agricultural extension system. The Farm Loan Act extended much needed credit to farmers. The Federal Aid Road Act sought to build modern roads to connect farms to markets. The Food and Fuel Control Act created the U.S. Food Administration during World War I. However, with this latter one, Houston’s competence comes into question because Herbert Hoover, who was nothing if not competent during these years, refused to head the agency if he had to deal with Houston in any way. Wilson capitulated on this and Houston was sidelined.

It took some doing to get Houston to be a useful Cabinet secretary. He was a very economically conservative man. People often overestimate how Progressive the Wilson administration was. Wilson was a Progressive, but his feelings about government was that it needed a few changes and then could revert to a conservative attitude. So he staffed his Cabinet with people such as Houston, who thought the same way. But like Wilson, Houston eventually realized that managing a modern state did require a more active government than he preferred. So at first, Houston opposed the ideas coming out of the farm belt to do things such as federal price support for cotton. But he realized that he could not fix the problems of American farmers with 19th century ideas and he later not only acquiesced but became a major supporter of the farm legislation of the administration.

However, Houston remained a close Wilson advisor. In 1920, when the odious Carter Glass resigned as Secretary of the Treasury to join the Senate, a now ailing Wilson tapped Houston to head the agency. This was only for a year and the equally awful Andrew Mellon took over for the next twelve years. He was not a major player during this year and didn’t have nearly the impact on the nation’s financial history as either Glass or Mellon. However, he did have one major task in that year and that was controlling inflation. This was a serious global problem in the aftermath of World War I. He was concerned it would spread to the U.S. He also worried about the decline in farm prices.

The U.S. had made a lot of mistakes in World War I when it came to agriculture. It may have made sense at the time to prime the pump to get farmers to grow an endless amount of food, but it had no plan to alleviate the debt burden those farmers would have once the war ended and crop prices declined. This was the start of the farm crisis that would help bring on the Great Depression in 1929. In fact, for farmers, the Depression basically started in 1921. Houston did try to work out some of these problems. He pushed for freer credit for farmers. He also tried to get them to produce less. But this was unlikely. It was very hard to get farmers to produce less when such a move relied on others do the same thing in order to raise prices. Without the kind of direct government intervention that the New Deal would finally initiate, there was little any official could do. Farm prices collapsed by early 1921 and Houston was blamed by farmers for it, perhaps unfairly, especially given that he was buying American food to send to Europe to help feed the people of that devastated continent.

After he left the government in 1921, Houston used his now considerable connections to become the type of senior political advisor the modern corporation came to cherish. He became president of Bell Telephone Securities and a VP at AT&T. Other corporations where he appeared in major leadership positions included U.S. Steel and Mutual Life Insurance Company of New York. No more agriculture for this rich connected guy. Harvard and Columbia brought him in to serve on their governing boards. He also wrote a memoir of the Wilson administration, Eight Years with Wilson’s Cabinet, publishing it in 1926. There was some talk about getting Houston the Democratic nomination for the presidency in 1924, but he squashed that pretty quick. You might think he was a bit obscure for this, but given that the Democrats ended up going with the exceedingly forgettable John Davis, he really wasn’t.

Houston died of a heart attack in 1940. He was 74 years old.

David Houston is buried in Saint John’s Church Cemetery, Laurel Hollow, New York.

If you would like this this series to visit other people who were Secretary of Agriculture, and who doesn’t want that!, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Jim Wilson is in Traer, Iowa and Edwin Meredith is in Des Moines, Iowa. It may not shock you to note that Iowa has been the home of many who have held this position. Previous posts in this series are archived here.