Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,092

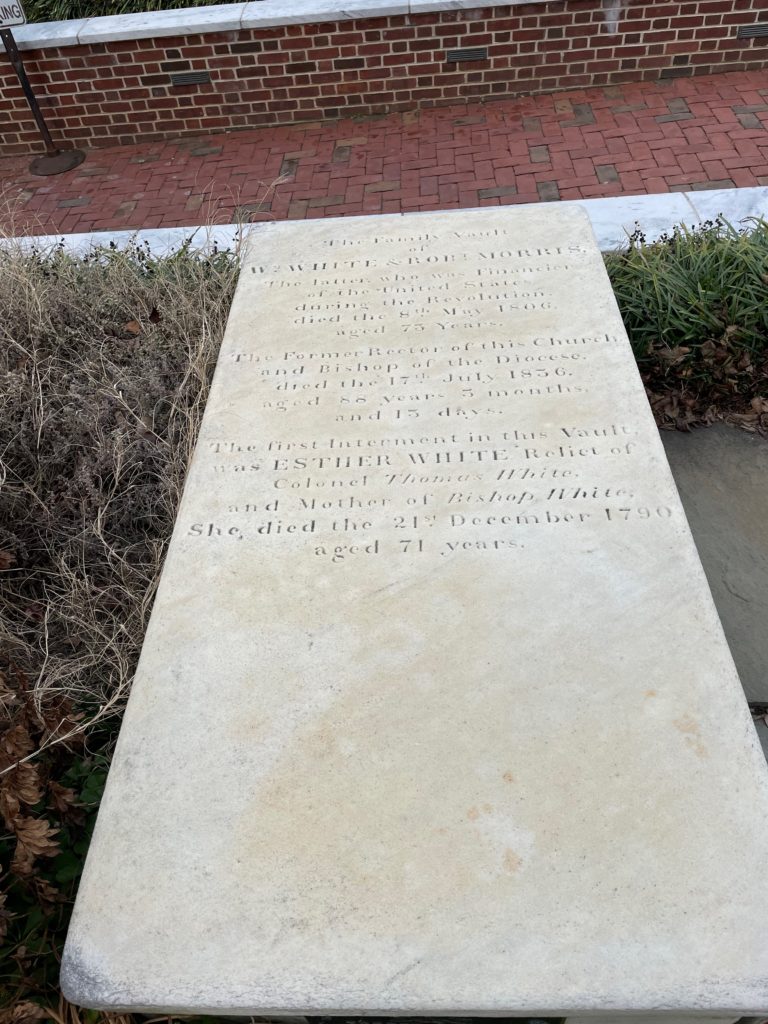

This is the grave of Robert Morris.

Born in 1734 in Liverpool, England, Morris grew up in a financier family. His father was a fairly prominent shipping agent working in tobacco. In fact, Morris was raised by his grandmother until he was 13, as his father was in Maryland working for his British company buying tobacco. I’m not sure where his mother was, perhaps she died when he was young. Anyway, Morris lived with his father in Maryland for a couple of years but then he was sent to Philadelphia for an education and to go to business. He became an apprentice for a leading merchant up there who was a friend of his father. Then in 1750, Morris Sr died and left his son his rather sizable fortune. Morris also picked up the world of finance and trading quite well and was soon in the Caribbean himself building up the business he worked for in Philadelphia. All of this meant that Morris was deeply involved in the slave trade and in fact was active in trying to get Pennsylvania to repeal its sizable tariff on imported slaves. Like so many northern fortunes, the money came from buying and selling human beings.

When the British started to try and force the Americans to pay for their violent genocidal wars by taxing them, Morris was part of the financial leaders in the colonies urging resistance to the new taxes. This continued for the entire decade as the discontent began moving to the American Revolution. What this meant is that when the Revolution broke out in 1775, Morris was all-in. Morris was key to the committee to organize defenses for Philadelphia and was the head of said committee when Benjamin Franklin was away. He also was a very good smuggler and managed to get the city quite a bit of gunpowder. Morris was not initially for independence. He was part of the more moderate faction in Congress trying to broker a deal. After all, the British were good for business if they didn’t make Americans pay any taxes to start their genocidal wars that were bankrupting the empire. But he was one of the few colonial leaders actually good at administration. He took charge of the Navy, which wasn’t much but it was what they had. He effectively ran it from Congress during much of the Revolution. He more acquiesced to independence than agreed to it. He refused to vote for it but just sat out the proceedings and didn’t oppose it either. He didn’t think it was a great idea but he wasn’t going to go against his Pennsylvania allies, however risky it was to his business interests.

With independence inevitable now, Morris used his capacity to see it through. His main job was organizing smuggling and finding ways to export American goods with the British banning any of that to its colonies. He hired pirates to attack British shipping as well. Morris agreed to stay in Philadelphia when it looked like the British would take it in order to represent American interests. He also was completely caught up in the ridiculous infighting in Congress that hampered the war effort. He and Henry Laurens, the South Carolinian who was president of Congress, hated each other and Laurens accused Morris of skimming profits. I really don’t know if this was true, but what I do know is that most of the Founding Fathers, if we want to use a stupid and useless term invented by Warren Harding of all damn people, were pretty bloody incompetent in the 1770s and 1780s. If anything, Morris was not incompetent.

Morris then worked primarily in Pennsylvania to create a state government that was functional. This set up much of what would exist once the new nation realized that it needed to actually govern, including an executive with veto power, a bicameral legislature, and an independent judiciary. Of course, it’s hard to believe that American democracy even remotely works today and the system set up by men such as Morris has been completely taken over by reactionaries in favor of plutocracy, but at the time, this was a useful innovation. During these years, he also worked on his shipping business and continued to get wealthy.

However, Morris was not to remain at the state level for too long. See, he was one of the only Americans with the wherewithal to actually understand finance. The Articles of Confederation were a complete disaster. In 1781. ten Pennsylvania regiments mutinied due to the terrible conditions of their enlistment. This finally got Congress to take these issues semi-seriously. So they brought in Morris as Superintendent of Finance. This made him one of the most powerful members of this new government, but that was pretty relative since his power was still quite limited. What he really did during these years was work with people such as Gouverneur Morris and George Washington to push for a stronger central government, slowly boring into those who were so scared of any centralized government that they would prefer to have basically nothing. Morris then released the Report on Public Credit in 1781, urging a tariff to protect American goods. But Rhode Island refused to go along. Under the Articles of Confederation, a 12-1 vote wasn’t good enough. Rhode Island became the blockade to any meaningful reform. The need to develop a real government was frustrated by the smallest state.

Morris kept pushing for financial reforms, such as a national bank, but the tiny things he could accomplish over the objections of Rhode Island still left him in a position of being unable to pay the nation’s soldiers at the end of the American Revolution. It’s hard for me to imagine anything more American than starting a war and then being unwilling to pay the people to fight it. Morris was so frustrated. He tried to resign in 1783 out of disgust, but Alexander Hamilton convinced him to stay on. Someone had to do it after all. Finally though, the next year he just couldn’t take it anymore and he resigned.

Not surprisingly, the next three years only brought more financial disaster to the idiots who refused to run a functional government. Finally, the Constitutional Convention met in 1787 to fix the problem. Morris was among those immediately advocating to trash the entire Articles of Confederation and start over. Morris would play a quiet but important role in the Convention. He left the legal arguments up to others and just tried to keep people’s eyes on the prize. He eagerly signed the final document.

Not surprisingly, when Pennsylvania ratified the Constitution, it selected Morris as one of its first senators. Washington actually wanted Morris to serve as Secretary of the Treasury, but he declined and recommended Hamilton instead, who was already close to the general. As a senator, he continued being involved in trying to build up the nation’s finances, working closely with Hamilton. He was also part of the compromise by which the nation would take over the state debts in return for building a new capitol city in the South, which of course became Washington. Over time, Morris became aligned with the Federalists, which is not at all surprising.

In his later years though, Morris played less of a role in national politics. He was trying to save his business interests. Through a combination of bad luck and bad investments, his empire collapsed. He contracted with the French to supply tobacco in exchange for French loans and personally guaranteed them. But then Thomas Jefferson, then minister to France, didn’t like this and interfered and it all left Morris on the hook. And then of course Morris was involved in the ridiculous land speculation of the era, which tied him up in the courts for years and eventually left him with more debt when he didn’t win out. It’s not as if Morris wasn’t still involved in major things. He built a big mansion. He was involved in canal building projects. He designed an icehouse that George Washington used at Mount Vernon. But the creditors just became too much. He invested heavily in land in Washington D.C., but couldn’t resell it for the profits he wanted and needed. By 1796, he was almost completely out of capital and started defaulting on loans. Then in 1797, the economy collapsed as part of the worldwide contraction due to the European wars. In short, Morris went to debtors’ prison.

Debtors’ prison was such a terrible idea. What use was there in putting Morris in prison? Moreover, it wasn’t like they put him to scare him or something. He really didn’t have the money. He languished in prison for over three years. He owed almost $3 million after all, in the money of the 1790s!!! Finally, Congress passed the Bankruptcy Act of 1800, which allowed people to be released from debtors’ prison if enough people agreed to forgive the debt. This passed in part because of outrage over the treatment of Morris.

But let’s be clear here–Morris might have been out of prison, but he really had nothing left. He lived his final years in a small Philadelphia house way out of the public center and that only because Gouverneur Morris found a loophole by which he could get Morris’ wife a little money each year from a land deal to pay for it. The only possession he still owned was his father’s gold watch. He did manage to leave this to his son. When Morris died in 1806, at the age of 72, he was almost totally forgotten about by the general public.

Robert Morris is buried in Christ Episcopal Church, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

If you would like this series to visit others of the founding generation, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. John Jay is in Rye, New York and Henry Laurens is in Moncks Corner, South Carolina. There aren’t really founders in the part of the South I am visiting later this week, but there sure are a lot of other terrible white people so keep this series alive! Previous posts in this series are archived here.