This Day in Labor History: April 28, 1941

On April 28, 1941, the Supreme Court decided the case of Phelps-Dodge v. National Labor Relations Board. The Court ruled that Phelps-Dodge and other companies who had strikes could not place workers on a blacklist and ordered them to hand over back pay as well. This important ruling undermined one of the major tactics companies used to crush unions and is one of the few pro-worker Supreme Court rulings ever.

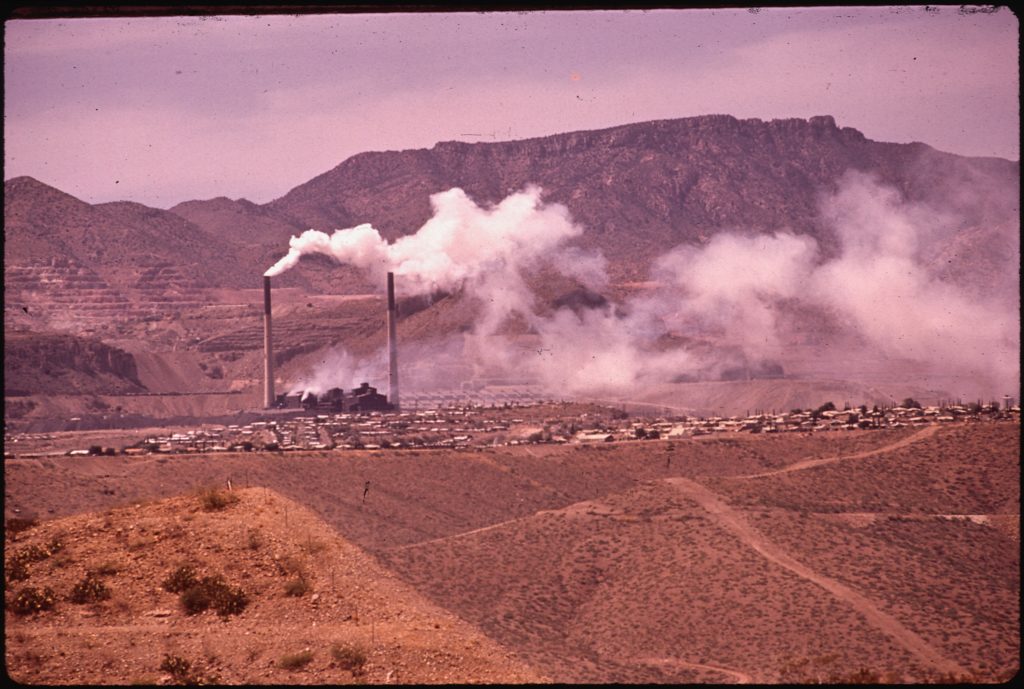

Phelps-Dodge was one of the most anti-union companies in the nation. It had long engaged in some of the most brutal union busting tactics in the country. That included the Bisbee Deportation in 1917. This was the moment when the company, facing strikes from its multitracial labor force, decided to form a posse, round up anyone they saw and suspected of being a union member (especially a member of the Industrial Workers of the World), load them onto train cars, and just drop them over the New Mexico border. This is one of the largest violations of civil rights in the entire awful history of capital and the state treating the American worker. And yet, hardly anyone cared and World War I became a moment when capital could eliminate unions with impunity so long as they had a few radicals in them so that the authorities would support it.

In 1935, the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers, or Mine-Mill, went on strike in Bisbee. This was the first major strike in Bisbee since the Deportation. Mine-Mill was the descendant of the Western Federation of Miners, that radical direct-action hard-rock mining union that had engaged in some of the most militant actions of the 1890s and had gone on to help found the Industrial Workers of the World in 1905. The strike went on for about two months. During this time, the National Labor Relations Act came into effect, which changed the rules for how companies could deal with labor unions. The company had won the strike. So it did what it always did–blacklisted strike leaders. But could it continue to do that? Many workers were fired, but two, by the names of Curtis and Daugherty, took the case to court.

What Phelps-Dodge had not anticipated is that Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter had been in Bisbee in 1917. Woodrow Wilson had not wanted to do anything to punish Phelps-Dodge after Bisbee because Cleveland Dodge, co-owner of the company, was his college roommate at Princeton and they were still good friends. But he had to do something, even if it was token. So he created a commission to investigate it. On that commission was the young lawyer and now assistant Secretary of Labor Felix Frankfurter. The future Supreme Court justice was horrified at what happened. He wrote at the time that the struggle of the workers at Bisbee was a “fight for the status of free manhood” by the Mexicans and southern Europeans who worked there, basically placing this struggle over the right for self-determination and what it meant to be an American. Now, nothing really came of all of this. Wilson was not going to crack down on anti-radical violence in World War I. But Felix Frankfurter sure remembered. Then Roosevelt named him to the Supreme Court in 1939. Phelps-Dodge’s tactics had barely changed. And he would have his chance to force them to change.

The Court ruled that the blacklist violated the National Labor Relations Act by refusing to hire the two men. Moreover, the Court found that the NLRA allowed the government to force the company to hire them. Who wrote the decision? Oh you know–it was Felix Frankfurter. The decision was just scathing. It placed the action of blacklisting workers into historical context, discussed the intent of the National Labor Relations Act in detail, and ripped Phelps-Dodge for its actions. Frankfurter could have gone even farther, but he was a moderate in terms of believing in aggressive court decisions. In fact, Frank Murphy, the excellent if short-lived justice who played such a critical role in the Flint Sit-Down Strike in 1937 when he was governor of Michigan, thought it didn’t go far enough and dissented in part, disliking the majority opinion that placed any constraints on NLRB actions on these issues. But the principle was set–a company such as Phelps-Dodge would not be able to engage in such punitive actions again, at least not legally. Of course, union activists have always had a hard time forcing companies to be held accountable for their actions, including firing unionists. Still, Phelps-Dodge soon had to accept unions in its workplace, as much as it hated the sheer idea of it. Like Ford and the Little Steel companies, the need for World War II government contracts forced their hand, which then helped solidify the role of unions in the United States through the maintenance of membership contracts that held through the war. That created forty years of unionization at Phelps-Dodge.

Phelps-Dodge remained a horrible company, leading the way in the 1980s private-sector unionbusting by forcing its workers on strike in order to bust their unions entirely, getting the state of Arizona to create a state-funded spy agency to help, and having Ann Coulter’s father run much of the operation. It won, freed itself from such things as having to listen to workers express any power at all, and returned to its historical role as an extremist company. Today, companies still fire workers for forming unions and at best face delayed minimal penalties for doing so. Unlike in 1941, the Supreme Court is now overtly hostile to anything unions do and the future of cases such as Phelps-Dodge v. NLRB remain pretty shaky, as year by year the Court undermines pro-union law.

I borrowed from Katherine Benton-Cohen’s Borderline Americans: Racial Division and Labor War in the Arizona Borderlands for the details on Frankfurter.

This is the 437th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.