Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,080

This is the grave of George Masa.

Born in 1881 in Osaka, Japan, Masahara Izuka came to the United States at the age of twenty. This was a common thing at this time. Japan sent many people to the United States during these years. Partially, this was about economic opportunity, but the Japanese also had a pretty honed sense of colonization and its intellectuals were for awhile at least relatively optimistic about starting large-scale Japanese communities throughout the United States. For more on this little point, read Eiichiro Azuma, In Search of Our Frontier: Japanese America and Settler Colonialism in the Construction of Japan’s Borderless Empire. It’s a quite fascinating book. Overall, about 400,000 Japanese left their home for the U.S. and its colonies, especially Hawaii, during these years. Moreover, hundreds of thousands more left for other places throughout Asia and Latin America, with Peru being a particularly notable landing place.

Evidently, Masa came to California initially to study mining. But not that much is known about his early years in the United States. In any case, he did not end up going into mining. By 1915, George Masa, as he now went by to make things easier for Americans, was in the service industry in Asheville, North Carolina, a resort town for the wealthy of the east, most notably the Vanderbilts. This was a bit unusual. The vast majority of Japanese immigrants remained in the increasingly large communities they developed on the west coast. So not many got to a place such as Asheville. It is however unclear why he made this decision. He was working at a fancy resort as a bellhop. His English wasn’t that great at this time. But he had also gotten really into photography and proved to be quite good at it. So in 1919, he decided to leave his job and become a full-time photographer. He was so good that his studio became the preferred company for the leading families in the area, including the Vanderbilts. This photography, much of which was your standard family stuff, gave him a steady income. Masa did face racism. We know for instance of at least one case when his boss at the hotel reported his suspicious photography to authorities, wondering if this weird Japanese guy wasn’t up to some no good. But we don’t know too many details about the daily racism someone like him would face, or at least the records are limited in this case.

With that income, Masa could engage in what he really loved, which was nature photography and nature exploration. Western North Carolina was a great place to do that. By the early 20th century, these mountains were both some of the last heavily forested lands east of the Mississippi and under a lot of threat from the growth of industrialization. The Vanderbilts and others had engaged in some pretty heavy duty land purchases that later became the core of what is today the Pisgah National Forest in North Carolina. But Masa did more than his part in this as well. He was known for exploring the mountains of the region and hauling himself up them, discovering their precise heights and cataloging them, of course also taking photographs of them while doing so. He became close friends with Horace Kephart, the local naturalist, and together they played a very important role in the establishment of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. When Kephart wrote about the mountains as part of the park drive, Masa took the pictures that accompanied his texts. Masa also did the basic surveying for what became the Appalachian Trail through the Smokies and North Carolina more generally.

Masa’s work is basically equal to that of Ansel Adams. Historically, it is just as important for having secured protection of one part of the country just as Adams did for the Sierra Nevada. But he is nearly unknown today outside of those who are really particularly interested in this sort of thing. Also, think about the physicality of all this. Masa was not a big guy. He did not have money for assistants. Good camera equipment was heavy at this time. He had to drag all this stuff up and down the mountains himself. He also was a locally important figure. The Asheville Chamber of Commerce routinely used his work to promote tourism in the area.

When it cost more than anticipated to buy out the many people who lived within the boundaries of the new park, the National Park Service sent the Rockefeller family a bunch of Masa photographs as part of its quest for a large donation to finish the job. Masa had photographed John D. Rockefeller Jr. when he visited the region in 1928, so there was a connection there. Rockefeller gave $5 million.

Unfortunately, in 1933, Masa came down with influenza and it killed him. He had lost all his savings in the bank collapses of the Great Depression that Herbert Hoover was so ineffective in doing anything about. So he was penniless when he died. That contributed to his death. He was just thrown into the county hospital where he wasted away with all the other poor people. A bit of money and he might have gotten the medical care that would have saved his life. He was only 52 years old. One of the mountains in the Smokies is Masa Peak, named for him.

In the aftermath of his death, those promoting the Smokies found Masa’s work very useful. When the writer Myron Avery wanted to get the government to put up the money to finish the southern part of the Appalachian Trail, he wrote a big article in Scientific American about it. What did he ensure was on the magazine’s cover that issue? A Masa photograph.

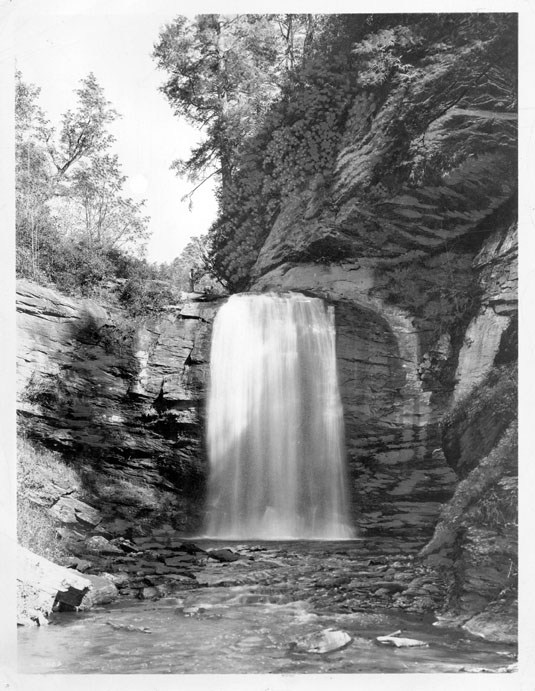

Let’s look at some of Masa’s work.

George Masa is buried in Riverside Cemetery, Asheville, North Carolina.

If you would like this series to visit other American nature photographers, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. William Henry Jackson is in Arlington and Timothy O’Sullivan is in Staten Island. Unfortunately, your 20th century nature photographer is exactly the type most likely to be cremated, so there goes an Adams post or many others. Previous posts in this series are archived here.