Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,062

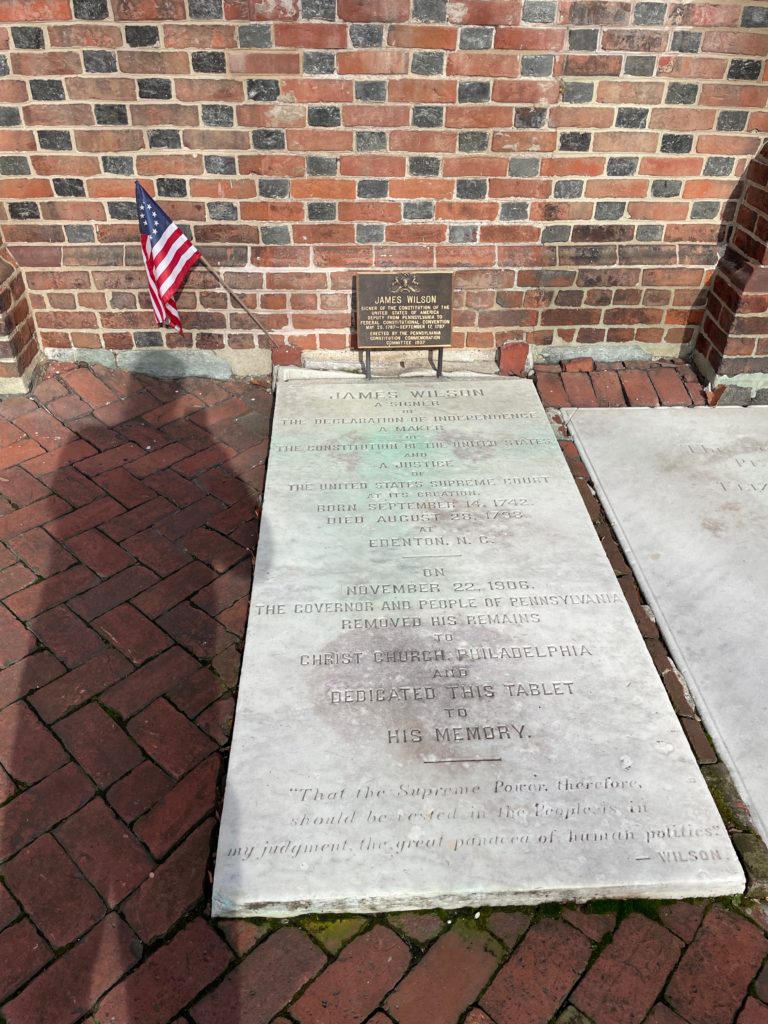

This is the grave of James Wilson.

Born in 1742 on a farm in Fife, Scotland, Wilson grew up in a fairly well off Presbyterian agricultural family. He was able to attend St. Andrews, Glasgow, and Edinburgh Universities, but he never finished. No matter though, as he studied deeply in the Scottish Enlightenment, second only to the French in its contributions to that intellectual movement. In 1765, again having not finished a degree but ready to get out in the world, he moved to Philadelphia in order to teach. He was excited about being part of the American Enlightenment around people such as Benjamin Franklin and Benjamin Rush and already interested in the growing dislike of colonialism in the colonies. He started teaching at what is today the University of Pennsylvania, who just gave him a degree for his credential.

Wilson also decided to study the law, working under John Dickinson, one of the leading lawyers of late colonial America. He was admitted in 1767 and practiced in Reading. He soon became one of the top lawyers in the colonies as well and made a ton of money. He also grew in his dislike of the British system of government. With the colonies moving toward open rebellion by 1774, Wilson made his contribution to the cause. He published a pamphlet called “Considerations on the Nature and Extent of the Legislative Authority of the British Parliament,” which pushed the idea that Parliament had no authority to pass laws regrading the colonies as the colonies had no representation there. Now, we do need to put these comments in some context, because the overly romanticized history of the American Revolution has made “no taxation without representation” the key cause of the fight. Well, maybe. But we have to at least consider this question from the British perspective. For Parliament, this argument was nonsense because all members of Parliament represented all of the country and the empire. Now you might say that is also nonsense and OK, sure. Britain had a long fight ahead for greater democratization, one that would not come into its own for another half-century after the American Revolution. But it’s not as if the idea of direct representation versus virtual representation was some obvious truth in 1774. To the British, these Americans simply didn’t want to pay their taxes and were making up philosophical arguments to justify to this. Some truth in that too.

Anyway, when the colonies decided to revolt against the British, Wilson was all-in. He was named a brigadier general of the Pennsylvania militia, but he didn’t fight. He had more value elsewhere. He was in the Continental Congress and was a strong advocate for independence, though he would not fully support a vote for it until he asked the people of his state about it in more detail. In 1779, Wilson defended property owners from the increasingly radical government of Pennsylvania that wanted to seize their property after the Fort Wilson Riot, where a mob had forced Joseph Reed, a leading Pennsylvania politician into defending his house, along with his friends barricaded inside. There was a shootout and a bunch of people died. This was the high point for Pennsylvania radicalism and it really scared the colonial elite about what they might have unleashed. Wilson took the lead on defending the wealthier people in the state that the radicals wanted eliminated.

Like so many of the so-called Founding Fathers (and damn Warren Harding for coining that term), he was looking to get rich off the revolution. He was heavily involved in land speculation, the sketchy way to wealth during these years, and ended up buying huge quantities of land in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and what is now Kentucky. He left the Revolution a very, very wealthy man.

All this meant that Wilson was a leader at the Constitutional Convention. He was not sympathetic with the incompetence of the Articles of Confederation and needed an orderly government to do his business. Generally though, he had more suspicion of centralized power than you would think from his actions of the previous years. He didn’t like the idea of the Senate and when it was inevitable at least pushed for direct election of senators and he also wanted the direct election of the president. Although Wilson himself owned at least one slave, he hoped the Constitution would outlaw slavery too. However, the Three-Fifths Compromise was actually articulated by Wilson, so…yeah….. More positively, Wilson was the prime mover in the Convention behind the creation of the presidency as a fairly strong and independent executive. Like most of these men, he believed the idea of political parties was anathema and he couldn’t really imagine how the nation could survive if they developed. This level of naivety, which extended much farther than Wilson, is hard to imagine now, but it gets at the shallowness of Enlightenment political philosophy.

Wilson was very close to James Madison at this point and while the former did not write any of The Federalist Papers, they shared many similar ideas. In terms of political philosophers at the Convention, only Wilson could really hang with Madison and so while he’s somewhat forgotten today because he never held big time elected office, Wilson is as important as anyone else in the establishment of this nation, with all of its warts. Moreover, the importance of The Federalist Papers at the time is a bit overrated–much of their fame has come in the two centuries plus since as statements of the nation during its founding. In fact, at the time, a widely printed speech by Wilson urging ratification even if you didn’t like all parts of the document (which included Wilson) was seen as more important in swaying public opinion at that moment. Wilson also hated the idea of the Bill of Rights. His belief that a government would never go beyond what was enumerated in the Constitution and so all these additional protections made no sense. Safe to say that Wilson remained a little naive about how actual politics would develop.

With the development of the government, Wilson had one job for himself in mind–he really wanted to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, even though what the Court would actually do was still very much up in the air. But George Washington chose his ally John Jay. However, Wilson received a nomination to be one of the Associate Justices of the Court and although disappointed, he accepted the offer. In truth, there was very little for the Court to do nationally. Wilson served on the Court for nine years. In that time, it heard nine cases. Most of what the justices did at this time was ride circuit to rule on more localized cases. For Wilson this was fine. See, he was so heavily engaged in land speculation and so unable to pay for any of it by the mid 1790s that he preferred to ride circuit in his southern district so he wouldn’t have to face his creditors. Moreover, he was absolutely creamed in the financial panic of 1796-97, when most of his land schemes went belly up and he had no money left. In fact, our Supreme Court justice served time in debtors prison in New Jersey, though he got out fairly quickly when his son paid off the particular debt. From that moment, Wilson tried to avoid any state where he had debts entirely. He went to ride circuit in North Carolina and just stayed. But that led to malaria. Then, still trying to recover from that illness in 1798, Wilson had a massive stroke and died. He was 55 years old.

James Wilson is buried in Christ Churchyard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This is not his first burial space. He was initially buried in North Carolina, but moved back home in 1906.

If you would like this series to visit other delegates to the Constitutional Convention, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. William Samuel Johnson is in Stratford, Connecticut and George Mason is in Lorton, Virginia. Previous posts in this series are archived here.