This Day in Labor History: March 9, 1892

On March 9, 1892, Memphis whites lynched three Black men–Thomas Moss, Will Stewart, and Calvin McDowell–who had dared to challenge white economic superiority in their community by opening a store to compete with a white-owned store. Thanks to the brave journalism of Ida B. Wells, this is probably the second most famous lynching in American history, behind that of Emmett Till. Moreover, it demonstrates the ways in which Jim Crow and the violence that supported it had a strong basis in continued white economic domination over Black communities.

Slavery was a labor system, designed to create a permanent labor force based upon a racial hierarchy. When slavery ended, whites intended to keep economic control over their former slaves. The Black Codes were intended to replicate slavery as closely as possible. The Freedmen’s Bureau intended on the other hand to enforce contracts between planters and the freedpeople. That didn’t work very well, but the ex-slaves demanded some level of economic emancipation and flat out refused to work in the gang labor system under white supervision that whites demanded. This led to the compromise of sharecropping, which was tremendously exploitative in its own right, but at least gave Black farmers some daily relief from white oppression.

As Jim Crow developed, it was only partially about economic issues and class. It certainly had that element, but with freedpeople now semi-independent in any number of ways, the white desire to control and dominate had more elements to it. But again, economics was a piece of it. The Ku Klux Klan specifically targeted Black people who had dared to purchase land, for instance. There were very occasionally and extremely limited attempts to create cross-racial class organizing, such as with the Colored Farmers Alliance or in the Knights of Labor, but we really have to squint to see anything more than the most rote idea of cross-racial solidarity from whites in these movements. For the most part, all whites saw all Blacks as people to exploit, economically and otherwise.

Memphis became a large Black city in the years after the Civil War, as ex-slaves poured into the city to escape the plantations. That led to enormous tensions and racial violence very quickly, as the Memphis Race Riot of 1866 killed 46 Black people. For whites at the very least, this was a community they could exploit. They could operate businesses that could wrest profit off of Black people and kill anyone who tried to stop them. In a mixed-race neighborhood in 1892, there was a store owned by a white man named William Barrett. He was a rounder as well. He ran a gambling den in the back of his place and supplied cheap and often illegal liquor to the community. He also had a monopoly in the area.

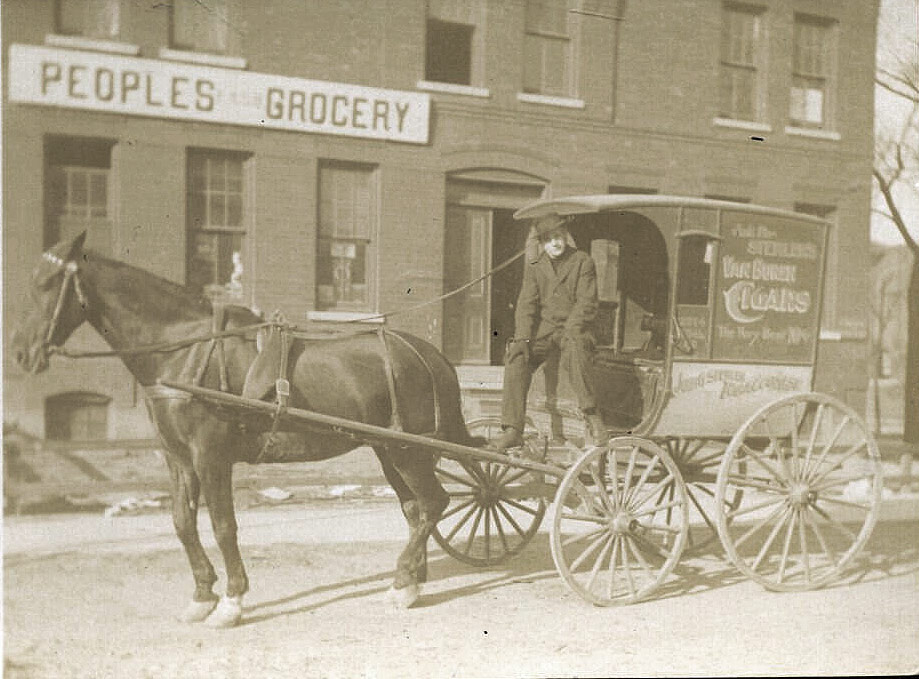

A big part of postwar Black uplift was about respectability and standing up for yourself. The idea of “Black manhood” was quite dominant in the period, which had multiple meanings, but in short was about defending yourself and your family from white depredations, raising the race through Black pride and ownership, and encouraging behaviors that would build these institutions. So disgusted by Barrett taking money out of the Black community, eleven Black leaders in the community opened what became known as the People’s Grocery. This was a cooperative store that sought to keep money in the community and create a space that would contribute to Black uplift. As a cooperative, it also sought to dignify the labor of its workers by bringing them in on something far more important than just a job. This was both an economic justice and racial justice organization, one dedicated to fighting the problems of the community on the ground.

This infuriated Barrett. These were HIS people to exploit. Yes, he also served the whites in the area, but he would not allow a Black owned store to challenge his personal economic domination. Probably the majority of lynchings had to do with economic competition. Someone challenged white economic domination and the response was murderous mob violence. On March 2, a Black boy and a white boy were playing marbles in front of The People’s Grocery. They started to fight, as boys will do. But the white kid’s father came to his son’s rescue and started beating the Black boy. That led workers inside the grocery to come to the defense of the Black kid. A big fight broke out. During the melee, Barrett got involved and he got beat up pretty bad. Things got bad after that. Barrett called the cops. When he came to the store the next day with a cop, he pulled a gun and pistolwhipped a worker. That worker grabbed the gun and shot back. The ground was laid for a lynching. This would combine talk of a supposed Black conspiracy to kill whites (obviously ridiculous). Then a white grocery store owner nearby shot a Black painter. A posse soon showed up at The People’s Grocery. The Black owners and workers were armed too. A shootout ensued. Several whites were hit, though none killed. Thomas Moss, one of the store owners, was there. So were two workers–Calvin McDowell and Will Stewart, both of whom were involved in the fight a week earlier.

A white mob came down on the prison. There had been Black defenders of them there, but when they heard all the shot whites would survive, they went home. Big mistake. The whites took them to a local rail yard and killed them after the usual horrible tortures. In the end, this was an act of economic terrorism as well as racial terrorism.

This might have been forgotten by the larger nation if it wasn’t for the brave journalist Ida Wells. She was already writing about lynching. Her work included documented cases of white women demanding Black men to sleep with them. Even beginning to write about white women wanting Black sex was enough to threaten her life. She was out of town when the lynching occurred. She was told not to come back at the cost of her life. She listened. She also was horrified by the loss of her friend Moss. She told this story and it got attention throughout the country. In fact, even the New York Times wrote a story horrified about what had happened in Memphis a couple of days later.

In conclusion, this lynching might not seem ideal for a labor history series. While the history of organized labor has a ton of material on organized racial violence against Black workers, this story does not have unions or bosses. But it is about economic emancipation and the ability to have a Black-controlled economy away from white domination. If it’s not exactly labor history, it’s labor adjacent and that’s close enough to me.

This is the 430th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.