NATO, Putin, and Ukraine

This is a guest post by friend of the blog and occasional contributor Jamie Mayerfeld. Jamie is Professor of Political Science and Adjunct Professor in Law, Societies, and Justice at the University of Washington.

A common (almost standard) position on the left is to condemn Putin’s invasion of Ukraine while stating that the United States contributed to the crisis through its long-term policy of expanding NATO to the east. Leftists commonly criticize NATO expansion as irresponsible, reckless, and provocative, and sometimes even as constituting a militarist and imperialist policy of the United States. It is commonly said that NATO expansion created legitimate security fears for Russia.

This view troubles me, and I want to try to say why. Before I do, let me first recommend the excellent discussions of this topic by Ilya Somin, Robert Person and Michael McFaul, Cathy Young, Tomas Klvana, and Lionel Page. I’ll note that I am not an expert on this topic, so readers should feel free to disregard my thoughts accordingly.

I think there are reasons to oppose but also reasons to favor NATO expansion. A key point is that NATO expanded largely because the former Warsaw Pact states and the Baltic states have demanded it. There is increasing support for NATO accession in Ukraine and Georgia, too. These countries have legitimate reasons, rooted in painful historical experience, for wanting to join NATO. They have been the victim of aggression by the Soviet or Russian regimes – conquest, occupation, invasion, and threats. The Soviet Union ruled the former Warsaw Pact and Baltic states through terror – mass deportation, purges, show trials, executions, censorship, and repression of political dissent. As the historian Klaus Richter reminds us, Russia’s neighbors to the west fear for their very existence.

It is a mistake to posit a consistent policy of the U.S. to weaken, threaten, or encircle Russia. George H.W. Bush tried to stop Ukraine from leaving the Soviet Union. In 1994 Ukraine gave up its nuclear weapons under pressure from the United States. In the initial years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the U.S. government opposed NATO expansion.

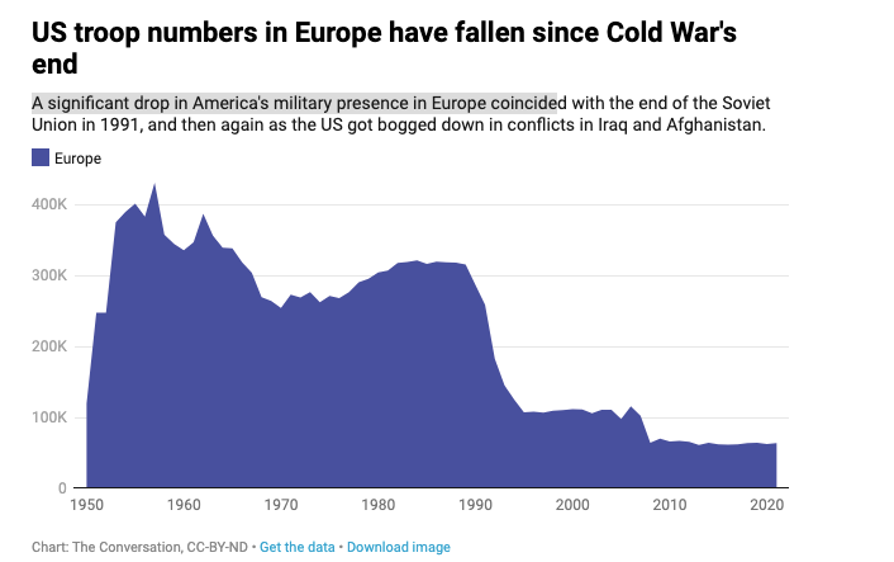

Starting in the late 1990s, NATO added several countries in central and eastern Europe, but that is not the only thing that happened. Since 1989, US troop presence in Europe has plummeted. See this article, which includes the following graph.

NATO has kept a light footprint in the Baltic states, and the U.S. has minimized its troop presence in the former Warsaw Pact states. It’s also important that after 1989 NATO took on a pro-democratization function, at least where Europe was concerned. It established strict democracy criteria for accession and this proved a strong incentive for democratization in candidate states. (Sadly, this hasn’t prevented autocratization in Poland and Hungary after they were admitted, not to mention Turkey.). It’s also striking that in the early 1990s NATO played a key role in getting the Baltic states to rescind legislation that discriminated against ethnic Russians. NATO stood up for the very concerns that Moscow says it cares about.

The United States made several gestures to allay Russia’s security fears, including the adoption of the Partnership for Peace, NATO Russia Founding Act, and NATO Russia Council. In the buildup to Putin’s recent invasion of Ukraine, the United States offered to pursue dialogue on a wide range of security concerns with Russia.

What about Ukraine? In 2008, the governments of Ukraine and Georgia each requested a membership action plan to join NATO, with the support of the George W. Bush administration. A membership action plan initiates the arduous process that is necessary for accession. NATO refused Ukraine and Georgia’s requests for a membership action plan, but sweetened its refusal with a statement that Ukraine and Georgia would become part of NATO. At the time, most Ukrainians were opposed to joining NATO. A Russia-friendly government came to power in Ukraine in 2010 and the request to join NATO was dropped. But after the Maidan Revolution of 2014 and Russia’s invasion of Ukrainian territory, public opinion swung in favor of NATO membership. In 2018, the Ukrainian parliament voted overwhelmingly to seek NATO membership and to enshrine this aspiration in the constitution. There was little sign that Ukraine would obtain its wish, since it still has not received a membership action plan, accession requires unanimous support from NATO’s 30 member-states, France and Germany were consistently opposed, and President Biden was publicly resistant to the idea.

NATO and NATO member states had no intention of ever attacking Russia. Current events confirm that powerfully. Even during a full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine marked by systematic war crimes, Western powers have carefully avoided attacking Russia. As Cathy Young writes, “If there’s one thing the last few days have conclusively demonstrated, it’s that Russia’s vast nuclear arsenal is a virtually insurmountable deterrent to NATO military action even in response to extreme provocation—let alone to an unprovoked invasion by land.”

By contrast, Ukraine had very real reasons for fearing aggression by Russia. It sought NATO membership for its own protection. Remember that Ukraine gave up its nuclear weapons in 1994! But over the years the Russian government has continually threatened and endangered Ukraine. It backed a pro-Russia party that used electoral fraud to try to seize power in 2004. It very likely poisoned the opposing candidate, nearly killing him. It heavily infiltrated Ukraine’s security services. It encouraged Ukrainian leaders in 2004 and 2014 to violently suppress pro-democracy protests. In 2013 it pressured Ukraine’s president to violate his promise to sign an EU association agreement. After the 2014 Maidan Revolution, Russia annexed Crimea. It encouraged, coordinated, and assisted the rebellion in the Donbas, and sent troops when Ukraine tried to regain control of its territory. It orchestrated rebellions, which mostly proved unsuccessful, in cities throughout eastern and southern Ukraine, as part of a plan to create a breakaway region called Novorossiya.

All this occurred against the background of Putin’s continual statements since 2008 and earlier that Ukraine is not a real state, that Ukrainians and Russians form one people, and that “true sovereignty of Ukraine is possible only in partnership with Russia.” Putin has venerated and empowered Russian revanchist nationalists who claim Ukraine as Russia’s patrimony. In his 7000-word article “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians” published last July, Putin spelled out his view that Ukraine should be controlled by Russia. The article is not an anomaly, but reflects views that Putin has consistently stated over many years and that he reasserted in the speeches immediately prior to launching his recent full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Talk of a threat posed to Russia by Ukraine’s potential NATO membership is overblown. In the first place, prior to the invasion, the prospects of Ukraine joining NATO were dim. And if Ukraine did join NATO, there would not be much added threat to Russia, just as the Baltic states’ NATO membership does not pose a significant threat to Russia. You can if you like imagine a hypothetical scenario in which Ukraine’s NATO membership threatens Russia, but it’s important to distinguish between real and remote security fears, actual motivations and talking points. (Putin’s recent behavior shows that he is willing to utter all sorts of lies, no matter how outlandish.)

Yes, Putin hates the idea of Ukraine becoming a member-state of NATO, but we need to ask why. The likeliest reason is not that he fears a threat to Russian security, but rather that NATO membership would establish Ukraine’s existence as a separate country free to make its own choices. Putin wants to make Ukraine a vassal state to Russia. The “vassal state” motivation does a better job than the “security fears” motivation of explaining Putin’s actual behavior over the past two decades.

Countries have a right to defend themselves and take reasonable measures to deter a potential attack. But they do not have a right to take unlimited action in response to the mere possibility that they could be attacked. They must limit their demands in light of plausible scenarios and must recognize and reasonably accommodate the genuine security fears of other countries. If certain countries take reasonable measures to defend themselves, other countries must not falsely construe those measures as offensive and thereby use them as a pretext for attack.

The problem with saying that Russia had legitimate security fears and that NATO expansion is partly to blame for Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is that it omits some parts of the picture while exaggerating others. It creates a lopsided view. It magnifies every remote and hypothetical security threat to Russia, while ignoring the very real security threats to Russia’s neighbors, and ignoring Western efforts to accommodate Russia’s security concerns. The framing reflects habitual blindspots that have distorted many left-wing perspectives on Vladimir Putin and Russian foreign policy.

Putin’s government demanded a promise from NATO that it would “never, never, ever” admit Ukraine as a member. I’m open to the possibility that NATO should have acceded to this demand, but I have no illusions about the reason why. The reason why NATO should have given in (if it should have given in) is that Putin made a demand and threatened to unleash destruction if his demand was not granted. It is not that the demand was in any way reasonable. It was in no way a reasonable demand.

Imagine that your neighbor is a predatory character who walks around with a machine gun, routinely threatens you, extorts protection money, invades your home, and steals your possessions. You think about acquiring a slingshot, and he threatens to kidnap your family members if you do. You now face a difficult choice, but it’s not because he has made a reasonable demand.

The above reflections are supported by events prior to Putin’s new full-scale invasion of Ukraine, but are reinforced by Putin’s current actions.