Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 990

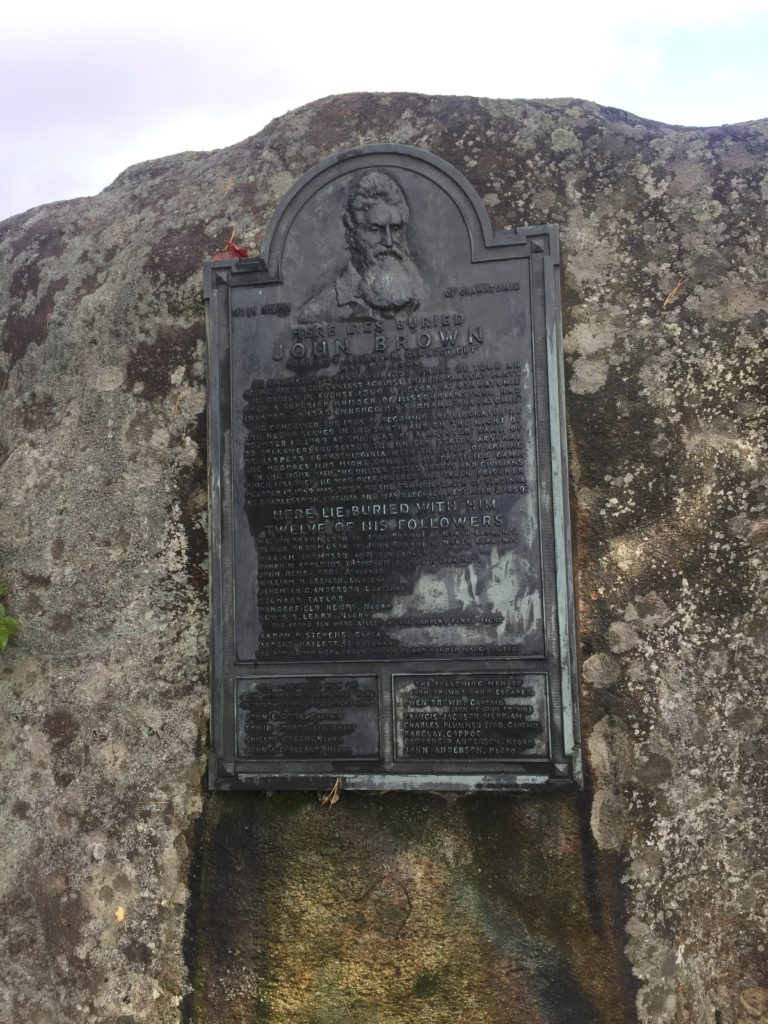

This is the grave of John Brown, as well as twelve of his men who died at Harpers’ Ferry.

Born in 1800 in Torrington, Connecticut, Brown grew up in an anti-slavery family. Even as early as the late 1800s, by which time the family had moved to the Ohio frontier, Brown’s father had strong anti-slavery beliefs. Incidentally, Ulysses Grant’s father worked for Brown’s father in the family tannery for awhile in those years. It was genuinely a small world back then. Brown studied with abolitionists such as Elizur Wright from the time he was a kid. In other words, he was unusually anti-slavery at a time when this was not a major issue among even liberal northerners.

Brown headed east as a teenager to get an education, but he was prove pretty rootless and unable to do much economically. He thought about being a minister, but came down with an eye issue that got in the way of his studies at Amherst College and he returned to Ohio. He became a surveyor, then opened his own tannery. He was in Pennsylvania for awhile in the 1820s and 1830s, where he raised his own children and where his farm because a key stop on the early Underground Railroad. He mostly supported himself through surveying, though he managed to become the local postmaster and held that job until he left Pennsylvania in 1835. His first wife died in childbirth in 1833. Brown then remarried fathered another 13 children, in addition to the 3 surviving ones from his first marriage. But Brown was pretty hopeless outside of his anti-slavery beliefs. He moved constantly after his Pennsylvania years, trying his hand at many different industries. He was saddled with debt and had no positive economic momentum in his life.

By the late 1840s, the wealthy abolitionist Gerrit Smith was giving away land to Black farmers to establish anti-slavery communities in the North. Brown heard about this and bought some of Smith’s land near Lake Placid cheap. That would be the home base for the family for the rest of Brown’s life, though he would hardly ever be there. That is because he was more concerned with freeing slaves than anything else by this point.

Brown was probably mentally ill, at least by some definition. That can mean many things, but his actions in Kansas, which heroic, also demonstrate someone with some clear issues. His oldest boys were out in Kansas and they wrote to their father about the slavers invading the place. So Brown decided to do something about it. He came out to join his boys. Bleeding Kansas was a violent place and time. Brown made it more violent. He came into the public spotlight for the first time in 1856 with the Pottawatomie Massacre, where he, his sons, and some other guys found some slaveowners and hacked them to death. This, not surprisingly, sent Brown’s sons spiraling down in the horror of what they had done. I mean, however just the cause, actually hacking someone else to death is quite likely to cause mental horrors. Humans aren’t meant for killing each other like that. But not Papa Brown. He wasn’t phased by the blood at all. He thought it was great. He also thought his sons weak. When pro-slavery forces killed one of Brown’s sons in the aftermath, he had his men killed about 20 members of the slaver militia. Brown was now infamous. He was a hero to the real radical abolitionists like Gerrit Smith, men who wanted to stand up to the slaveowning power. He was evil to the slavers. He was also tremendously brave. While he was now an underground figure, Brown, on one of his risky trips back to Kansas, heard about some slaves being sold south in Missouri. He raised a small force to free them, killing at least one of the slavers, and personally guided them north, all the way to Detroit so they could to Canada and escape slavery for real. So no one can question his bravery or his true commitment to the cause.

This whole time, Brown was talking about a bigger action against slavery. He got Smith and other wealthy supporters to pay for a bunch of pikes his men could use. But he didn’t have the money to put anything together. The pikes stayed in storage for a couple of years. Brown was no better with money after 1856 than he was before. He continued to drift. As early as 1842 he was talking about some kind of bigger action. But like a lot of people such as Brown, it seemed like it would never actually happen. But he did know basically everyone in the abolitionist community and if Brown came across as unhinged, well, that was a positive for radicals attempting to break an evil system by any means necessary. They were happy to give him money. The Secret Six–Smith, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Theodore Parker, George Luther Stearns, Samuel Gridley Howe, and Franklin Sanborn–handled the fundraising. These were respectable people with respectable, if radical, Victorian politics. So Brown might have preparing to engage in an insane action that had no chance of success. But he had benefactors ready to fund anyone who would take on the horrors of slavery.

And let’s be clear here–Brown is one of the true anti-racist whites of the 19th century. You can’t say that about Abraham Lincoln. You can’t say that about a lot of the abolitionists, many of whom were also happy to engage in genocide against the tribes. Brown also found this disgusting. He really truly was friends with Black people in a way that few whites could imagine.

As Brown prepared his big plan–take over the U.S. arsenal at Harpers’ Ferry, free a bunch of slaves, and then head up a guerilla force in the mountains that would lead to a genuine slave revolt–he tried to get Frederick Douglass to join him. Douglass and Brown knew each other well. Douglass did not join, because, you know, the plan was completely insane. But Douglass’ top assistant did join and Douglass was fine with that. Fighting for freedom–forget this non-violent crap that late 20th century and early 21st century liberals turned into a fetish–that was what Douglass was about, as were many of the abolitionists. Harriet Tubman actively helped him recruit people for the mission, which she completely supported. So if you think John Brown was wrong for using violence, well, was Harriet Tubman wrong?

Of course the raid on Harpers Ferry was a complete cluster. He only had 21 men. They had no chance of success. Brown probably knew this. But he was aging and he was happy to play the martyr. He was born for that. He certainly had no fear of blood, as we saw in Kansas. He didn’t fear losing his own blood either. He was nearly killed in the raid, as were most of his men. But despite his grievous wounds, he held his own during the trials that followed. I don’t think we need to go over all the details here. They are well known and you can look them up.

What makes Brown especially interesting to me how the South reacted in the aftermath of the raid. Of course Virginia wanted him dead. Governor Henry Wise wanted to use executing him to become the real voice of southern extremism. But here’s the thing–southern elite society was very violent. It was a honor-bound society of men who knew guns, booze, and killing. They raced horses, they gambled, they raped their slaves, they ruled their homes by the fist against wives, children, or slaves. Northern elites rejected all of this. The rise of Victorian middle-class norms meant disgust toward these southern ways. This led the South to think that northerners were a bunch of wimps that would cower at first violence. This is one big reason why southern leaders thought they could easily win in the Civil War. But Brown? He didn’t have much time for all those Victorian values. That he went into the South, invaded the federal arsenal, was happy to kill for his beliefs, and then tell his captors that he wished he had killed them–well that was southern manhood personified. They were fascinated and horrified by Brown. For them, Brown was way scarier than William Lloyd Garrison or Smith. That’s because he would pick up the gun. He combined both northern and southern ideals of masculinity. That’s a big part of the reason why the South so feared him.

Now, after the raid, all of Brown’s supporters freaked out. Smith even left the abolitionist cause. Some fled to Canada. He didn’t care. He was going to go all the way to the gallows and never apologize. So while he was condemned roundly after the raid, by the time of his death later in 1859, he was already being seen as a martyr to the cause, something that would only grow after the South committed treason in defense of slavery less than two years later. In fact, Victor Hugo became a huge fan and circulated letters in the U.S. and Europe demanding his pardon. Now, Henry Wise didn’t care what Victor Hugo had to say and neither did Robert E. Lee, but this was still significant. And it’s probably what Brown wanted. He went down the way he lived. Whether you consider him a terrorist or a freedom fighter, well, that’s up to you.

As you can see from the picture above, most of Brown’s followers are also buried with him. They are some fascinating people in their own right. This post is already so very long–and in fact, I could probably write another 2,000 words on Brown without even trying–that I am not going to go into them. But each is a hero, doing whatever it took to stand up to an evil system that defined the United States and really continues to do so. He rejected not only southern slavery, but the racism that many northern liberals felt toward Black people. If we consider Brown a hero today, I think it only makes sense if you take up active anti-racism in your own life and channel his spirit into doing something about the many ways you benefit from racism every day, if you are white at least. Otherwise, you’ve learned nothing from him.

John Brown is buried at the John Brown Farm State Historic Site, North Elba, New York.

If you would like this series to visit other abolitionists, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Tomorrow, I start on another grave trip to rejuvenate the list of people I will profile, one that had to replace a hoped for international trip that Omicron’s disruptions defeated. But what’s more socially distanced than the boneyard? I am heading to the South–of course, all the best people are there….–so abolitionists are unlikely. But you never know! Anyway, Jonathan Walker, who had an “SS” branded on his hand for his “slave stealing” by the law in Florida, is in Muskegon, Michigan, and Jonathan Fairbank, who served serious time in two different stints in Kentucky prisons for helping slaves escape, is in Angelica, New York. Previous posts in this series are archived here.