Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 988

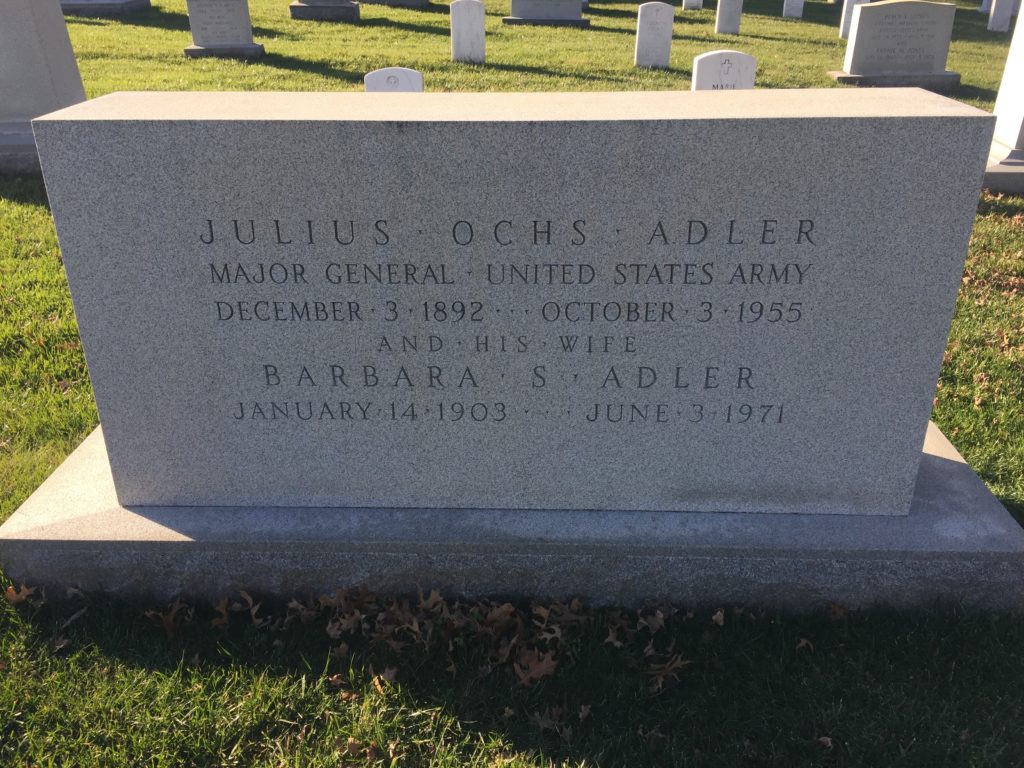

This is the grave of Julius Adler.

Born in 1892 in Chattanooga, Tennessee, Adler grew up in one of the nation’s most elite families. The Ochs in his name is the New York Times Ochs and young Julius was groomed for leadership. He grew up in Chattanooga before entering into some of the nation’s fanciest public schools. He went to Princeton, graduated in 1914, and then joined the family business.

But in 1917, Adler’s career took a curveball. He went into the military. He was interested in military stuff before this. There were lots of rich young men in this era who romanticized war and were really excited to prove their manhood on the battlefield and I assume Adler was one of them. He entered the Citizens Military Training Camp in 1915 which was a program out of the preparedness movement at a time when most Americans had no interest in fighting in World War I (which actually may not have changed much by 1917). When the U.S. did enter the war, Adler, commissioned as a second lieutenant the next day, led the 306th Infantry Regiment, 77th Infantry Division. By this time he was already a captain. These were brutal battles, especially in the Meuse-Argonne Campaign. Adler was gassed. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, two Silver Stars, a Purple Heart, the French Croix de guerre and the Italian War Merit Cross. That he was a rich kid from a hugely powerful newspaper helped in all these medals, sure, but that doesn’t erase the real battles he led troops into. After all, he personally captured 50 Germans with just a pistol late in the war.

Adler went back to the paper after the war, though he remained in the reserves. He rose rapidly in the company. In 1935, Adler became general manager of the Times. He also remained committed to military preparedness and as the Nazis rose in Europe, Adler was one of the main forces behind supporting the Allies and getting the U.S. ready for war. He did that through the paper, yes, but also through training young people in military techniques, like he had been involved with before World War I.

In 1940, Adler left the paper and rejoined the military. Once again, he put himself first when calling for war, which to say the least later generations of our politicians and newspaper editors of [cough] certain newspapers did not. He became assistant division commander of the Army’s 6th Infantry Division in the South Pacific. He was in New Guinea in 1944, but, like so many other soldiers, got sick (malaria, I think) and it was so serious that he was discharged from the military late that year.

Adler returned to the Times, though he remained in the Army Reserve. He also ran the Chattanooga Times. Interesting that the family was so invested in their small-town southern paper for so long. He also became a really useful tool for the military and was invited by leading generals to the postwar proceedings. He inspected concentration camps with Eisenhower (I can’t imagine what that must have been like for a Jewish person) and he reported from Asia at the end of the war. Adler eventually reached the rank of major general in 1948, even as he was in the reserves. He retired entirely in 1954. But he died the next year at the age of 62.

Julius Ochs Adler is buried on the confiscated lands of the traitor Lee, Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia.

If you would like this series to visit other officers of the New Guinea campaign, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. George Kenney and Robert Eichelberger are also both at Arlington; to say the least, one needs many trips to Arlington if they are serious about this series. And they are serious. Speaking of which, this series is hitting the road in a few days to replenish its collection of dead Americans. So, you know, help make it happen if you like what we do here. Previous posts in this series are archived here.