Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,001

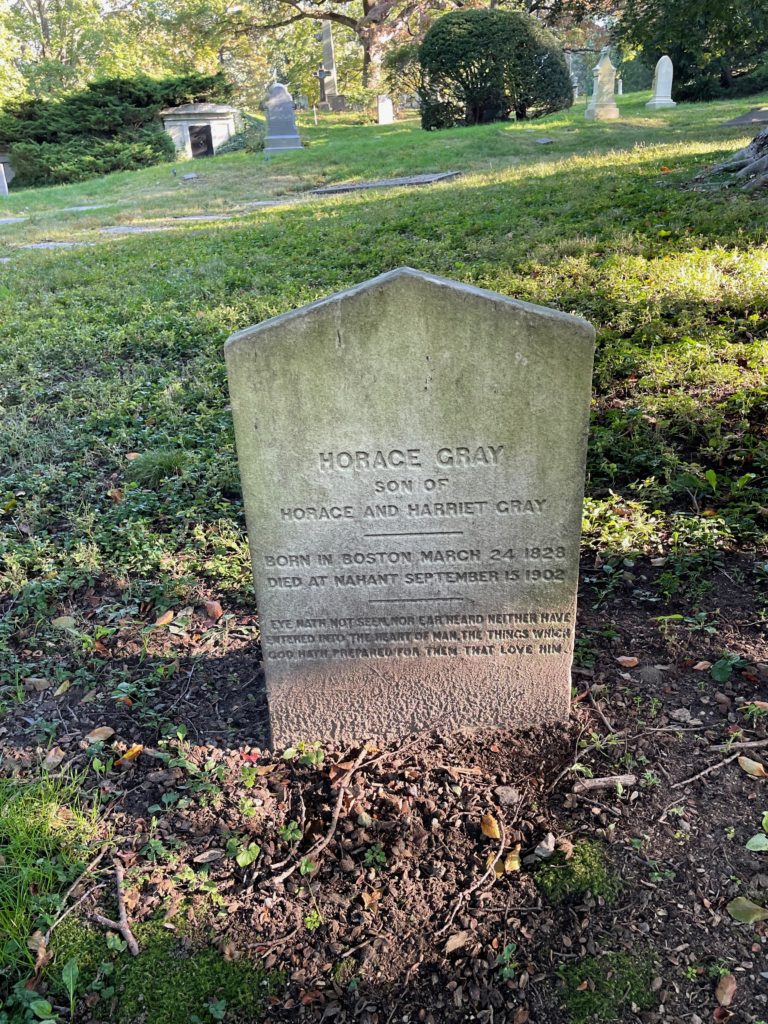

This is the grave of Horace Gray.

Born in 1828 in Boston, Gray came out of the early republic Boston elite. His grandfather was William Gray, who had built a family empire and became New England’s richest man. Gray’s politics were definitely shaped by the massive wealth of the family. He went to Harvard at the age of 13 and graduated at the age of 17, right about the end of the era of young teens entering college. He then went to Harvard Law, finished his degree in 1849, passed the bar in 1851, and practiced law in Boston until 1868. He was a strong Republican, one with a Radical background. He was a Free Soiler and a friend of Charles Sumner.

In 1854, Gray was also named Reporter of Decisions for the Massachusetts Supreme Court. What this meant was that not only did he edit and publish the volumes of the decisions, but it required him to become an expert on these issues and he soon became a chief legal advisor to the state and its governors. He became one of the state’s leading legal experts. So in 1864, he was named to the Massachusetts Supreme Court himself, the youngest appointee in the state’s history, only 36. He became chief justice of that court in 1875. While there, he started a new tradition that would become one of his leading contributions to the history of American law. He hired a law clerk. That was a new thing. Said law clerk’s name? Louis Brandeis.

In 1881, the less than legendary Nathan Clifford, who was on the U.S. Supreme Court, dropped dead. Chester Arthur nominated Gray to replace him. It was an easy confirmation and he started in 1882. There, he also named the first law clerk in the Supreme Court’s history. At this time, Gray paid his law clerks out of his own money. Of course, he had a lot of it. That man did believe in legal research, which is maybe the one really positive thing one can say today about this Gilded Age suit. Interestingly, Arthur seems to have chosen Gray because he was seen as above the fray. Since the only thing anyone knew about Arthur was that he was a political hack who had risen to power based on patronage. So who was less connected to patronage networks than the extremely rich legal historian jurist from a state where Arthur had no important connections?

On the Supreme Court, Gray was a classic Gilded Age justice. Property and precedent are what mattered. Gray had a huge hang-up over the idea that politics and the law were completely separate and must be kept that way. In fact, unlike most Supreme Court justices of the time, he had no political background. But this idea that politics and the law are so separate, which is very prominent among Elite Law Brain People today, was just as ridiculous in the 1880s as it is now that the Republican Supreme Court is deciding the Founders had in mind every position of the contemporary conservative movement. Well, Gray was basically the same. The thing about this as well is that was Gray was known for having very strong opinions about everything in life. One person who knew him noted “he was a man of strong prejudices, religious, political, literary, and social, which often affected his bearing toward those with whom he came in contact.” He claimed there were these big differences between politics and the law, but his decisions nearly always just reinforced his preexisting beliefs, especially around property and also around race. He generally supported government power over financing, which was very important to him. He wrote the decision in Julliard v. Greenman in 1884, which declared definitively that the U.S. had the right to issue paper money during peacetime. He was always a consistent vote on these types of issues.

If Gray’s jurisprudence is known for anything today, and really it’s not, but if it is, that would be Mutual Life Insurance of New York v. Hillmon, an 1892 decision he wrote that basically introduced the concept of the state-of-mind hearsay exemption to legal cases. In short, something that someone had said or written that stated intent in the future could be used in a case against that person for a crime committed.

On race, Gray was as complicated as most Republicans of the time. He authored the very important decision in U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark in 1898, which said that a child born in the U.S. of Chinese descent was an American citizen. This was the rare defeat for anti-Asian nativists at this time and also an extremely critical decision under the Fourteenth Amendment that grants citizenship rights to anyone born in the U.S. except for the children of diplomats. Of course overturning this is at the very top of the agenda for the Stephen Miller wing of the Republican Party and we will have to see what the Court does on these issues going forward. It’s also worth noting that the Wong case was a bit of an outlier for Gray because he had previously ruled consistently that Congress should control immigration issues, such as in Fong Yue Ting v. U.S., a 1893 decision that helped find the Chinese Exclusion Act and other anti-Asian exclusionary laws constitutional.

But while Wong might make Gray seem like one of the good guys, he was also one of the 8 jurists to vote for segregation in Plessy v. Ferguson two years earlier. The key point about Plessy that I make repeatedly to demonstrate the overwhelming white supremacy of the time is that while the Republican Party was supposed to be the party that ended slavery, it was just as committed to white supremacy as Democrats and by 1896, nearly all the Supreme Court justices had been named by Republican presidents, not to mention that the one who voted against Louisiana here was the former slaveholder John Marshall Harlan! In fact, with the exception of Wong, Gray was a consistent vote for white supremacy in the many cases around race the Court heard at this time, against Black, Native, and Mexican-Americans. And yes, that’s right–Charles Sumner’s good buddy was one of the justices who decided Plessy in favor of segregation. Such was the limited racial vision of most white abolitionists.

Gray was all about precedent. In fact, the farthest right conservatives on the Court worried about this because they feared he would support the congressional regulation of commerce, which could potentially undermine business dominance. Gray never really did this, but one can be curious as to how he would have founded in Lochner given he did hold to some level of principle on these issues. On the other hand, in Alaska Mining Co. v. Whalen, an 1897 case, he ruled that a company could not be held financially accountable for a case where an employee was hurt, even though it was the fault of the company’s foreman.

Gray stayed on the Court until he died. That was in 1902, when he died at the age of 74. He had actually resigned a few months earlier but on the condition that his successor was confirmed, which had not happened yet.

Horace Gray is buried in Mt. Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

If you would like this series to visit other Gilded Age Supreme Court justices, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Nathan Clifford is in Portland, Maine and David Brewer is in Lansing, Kansas. Previous posts in this series are archived here.