The Games of 2021

If I had to sum up the focus of my gaming in 2021, it would be: the comfort of the familiar. I spent a lot of time this year re-gaming, playing games I’d already completed all the way from the start (in some cases, with the excuse of having a fancy new computer to try them out on, but sometimes just seeking familiarity), searching out remastered versions of games I loved years ago, and even, as you’ll see further down this list, picking up new games because they reminded me of ones I once loved. A hallmark of a game I enjoyed in 2021 was my willingness—eagerness, even—to replay it again and again, and the games that scored highest with me were the ones that rewarded that repetition with an interesting world, a story whose secrets continue unfolding even when experienced for the second or third time, and an efficient, satisfying mechanic that doesn’t drag or lose its flavor with familiarity. It’s not hard to guess why I was attracted to games like this in 2021, to new worlds that nevertheless feel comforting and predictable. It also means that I have a Steam library full of new games waiting for me, and yet I keep going back to the ones I already know. Still, I did manage to play a few new things this year, and if you’re like me and are looking for something that rewards repetition, you might find it here.

(One place where familiarity failed, or perhaps was drowned in the uncanny valley: 2021 was the year I finally made the switch from Civilization V to VI, which I played for a few weeks, and then promptly put down, perhaps forever. It’s actually a little stunning, how much the new edition has killed my love of the game—I don’t even feel like going back to V. I can’t really put my finger on why VI doesn’t work for me—maybe it’s the graphics, or the way the ramp-up to a semi-stable level has gotten much harder and slower, or the more aggressive barbarians and enemy players—but I used to start up Civ at the end of the day just to tool around a bit, and now I have zero interest in doing that, much less committing to a whole game.)

One game that isn’t on this list is Hades, because I barely got more than an hour into it before quitting in frustration. I should stress that this is, in all likelihood, a me problem. Fighting games have never been my forté, and if the developers of Hades hadn’t been generous enough to offer evaluation codes for voters in this year’s Hugo awards (where the game was nominated in a special category, which it eventually won), I probably would never even have tried it. But everyone I know loves Hades, and stresses its strong storytelling and characters. And, well, even in God Mode I couldn’t get far enough into the game for these to appear. Maybe I’ll give it another shot in 2022, but in the meantime, I’ll just have to take everyone’s word that this is a game I might enjoy.

The Witness (2016)

I actually played most of The Witness in 2017, then wandered away for some reason. I ended up going back to it at the beginning of this year through the confluence of several factors. First, general boredom, what with the narrowing of entertainment options as the backlog of new TV series and movies became depleted. Second, having played Quern in 2020, another game that riffs off Myst and similar exploration-and-puzzles-on-an-island games, and remembering how much more interesting The Witness’s take on the form was. And third, and perhaps most unexpectedly, having read Susannah Clarke’s magnificent, haunting Piranesi. The two works, book and game, have a very similar vibe. They’re both about exploring a world that is a puzzle, and eventually coming to realize that it is the exploration, not the puzzle or its solution, that is the point.

That The Witness conveys this impression so successfully is all the more impressive given that its puzzles are so prominent and insistent. The island on which the nameless, faceless player character appears and has to explore is littered with game boards, grids on which you have to draw a path according to rules that grow more convoluted and varied as the game progresses. Each area of the island teaches you how to solve a certain type of puzzle, and then subsequent areas mix and match elements from previous ones to create increasingly devilish challenges. (I freely admit that I resorted to walkthroughs at a certain point.) In any other game, the result would be entertaining but mechanical, but even as it draws attention to its game-ness with these puzzles, The Witness creates the impression of something greater. The island is full of distractions—lifelike statues that appear to have been frozen mid-motion, recordings that wax philosophical about scientific exploration and being open to new experiences, video clips from art-house movies. Where other island exploration games try to tell a story through the structures and artifacts they scatter throughout their landscape, The Witness overwhelms the player with the impression of a story, even as the glut of information and suggestive imagery makes it clear that no single answer could explain all of the island’s weirdness. Even the game’s endings (including the secret one that gives you a look at its backstage area) offer more questions than answers.

The Witness’s most stunning achievement is how it strikes a balance between the constant forward motion of getting to the next puzzle, opening the next locked door, exploring the next area, and the growing sensation that the point of the exercise is simply to explore, to find a hidden pathway or a spot with a nice view, to learn the world not as a means to an end but because that learning is a worthwhile pursuit in its own right (which is also the point made in Piranesi, and the reason the two works seemed so similar to me). It’s perhaps for this reason, however, that I found The Witness easy to put down four years ago (I don’t seem to be alone in this—only 18% of Steam players have gotten the achievement for finishing the game). Once the point is made, it can be fun to simply wander the island, but eventually you’ll find another distraction.

The Gardens Between (2018) and Old Man’s Journey (2017)

I purchased these two games together in a Steam bundle, and they end up working well as a pair. Both are beautifully animated and soundtracked journeys through their main character or characters’ treasured memories, with the player having to master a central mechanic to allow the character forward motion through those memories. In Gardens, these are two children who have lived next door to one another for years. In Journey, an old man who is reminiscing about his life as he travels—on foot, and via train, boat, truck, and hot air balloon—to an unknown destination. Both games even use a storm to illustrate their characters’ increasing inner turmoil as their story draws closer to the trauma that drives them.

Gardens, by Australian studio The Voxel Agents, is a game about manipulating time. By pressing the left and right arrows, the player moves the characters not in space but into the future or past. Certain items, however, are immune to the motion of time. Manipulating them can change what happens when you reverse into the past or advance into the future. Other items can accelerate time for certain parts of the environment but not our protagonists. So a collapsing structure can be accelerated so that its pieces form a bridge at just the right place and time for the characters to cross. It sounds complicated, but the game is very good at introducing the mechanic organically and teaching the player how to take advantage of each different element on the screen. Journey, by Vienna-based studio Broken Rules, asks the player to manipulate space. Instead of getting its elderly protagonist to jump across caverns or scramble over cliffs as he progresses in its journey, the player changes the landscape itself, moving the rolling hills of the game’s rural landscape so that they form a path for the old man to follow, or create a track for a train to travel on. It’s a much simpler mechanic, and eventually it overstays its welcome.

Both games take about two or three hours to play, but Journey feels longer because its puzzles are more repetitive, and because the old man’s story is a great deal less sympathetic than the game clearly expects it to be. As the game progresses, we discover that he abandoned his family for a life of adventure and exploration, which he now regrets. There have certainly been stories that have created sympathy for characters like this, but the wordless, candy-colored, and almost twee storytelling of Old Man’s Journey can’t achieve that complexity, which left me increasingly uninterested in helping the character reach his destination (and an unearned forgiveness). Gardens is similarly working with shopworn material—two children reminiscing about their shared adventures as one of them prepares to move away—but the smallness of this tragedy suits the terms in which the game puts it—the two friends would like to be able to reverse or stop time, and prevent their separation, but in the end what they are left to hold on to are the memories of the time they had together. Neither game is a must-play, but The Gardens Between has the more interesting puzzles, and the more compelling story.

The 13th Doll: A Fan Game of The 7th Guest (2019)

Along with Myst, The 7th Guest was a game that I imprinted on as a young teen, and which continues to define the kind of games I’m interested in, even thirty years later. But whereas Myst aroused wonder and the joy of exploration, The 7th Guest aroused terror and anxiety. Its imagery—the wood-paneled corridors and tastefully decorated interiors of Stauf mansion, and the eerie ghosts reenacting a night of tragedy and bloodshed within it—and its brilliant soundtrack, by George “The Fat Man” Sanger, still have the power to send shivers down my spine. Developers Trilobyte quickly followed up the game’s success with a sequel, The 11th Hour (1995), which seemed to miss everything that players loved about the original game—obviously, the thing you want as a follow-up to a rich, luxuriously-realized period mystery is to wander the same halls in the present day, tripping over smashed TVs and piles of old newspapers, while watching video cut-scenes of sullen, annoying characters. So it was thrilling to discover that a group of fans, assembled under the name Attic Door, had secured a license from Trilobyte (and Kickstarter funding) to create another sequel. The 13th Doll is far from a perfect game, and it doesn’t reach the heights of the original. But it feels like a labor of love, one that—as is sometimes the case with fanworks—understands far better than its creators what was evocative and compelling about the original game.

Discarding the sequel’s story entirely, The 13th Doll returns to Stauf mansion a decade after the events of the original game. Sole survivor Tad Gorman is now confined to an asylum, still haunted by his experiences. At the behest of new psychiatrist Dr. Richmond, Tad re-enters the house, hoping to (literally) lay some ghosts to rest. Tad and Richmond are both playable characters, each with their own storyline, path of exploration through the house, and puzzles to solve, all converging on yet another devilish scheme by toymaker Henry Stauf (a role reprised by original performer Robert Hirschboek, who is also credited on the game’s script). Along with the loving recreation of the house, and the new soundtrack—which recalls Sanger’s without being pure imitation—these puzzles are the game’s main claim to fame. Clever, challenging, and perhaps most importantly, in clear conversation with the original game’s puzzles and story, they create a sense of continuity, and of great fannish love. Less successful is the game’s story, which starts out with a lot of interesting ideas that it doesn’t quite know how to follow through. As in a lot of fan productions, the acting is also an Achilles’ Heel, with either the script or the director having forgotten to remind the performers that they’re meant to be playing people from the 1940s. So The 13th Doll can’t quite deliver an experience on the same level as the game it’s clearly in deep awe of. Still, that awe shines through and makes even the ropier aspects of the game worth experiencing. If this isn’t quite the sequel that The 7th Guest deserved, it’s a lot closer than we’ve ever gotten before.

80 Days (2014)

There have probably been dozens of games—computer and board—on the general theme of attempting to recreate Phileas Fogg’s round-the-world journey from Jules Verne’s 1873 novel. I haven’t played most of the others, so I can’t say that 80 Days, from British game studio Inkle, is the best of the bunch. But it’s an excellent example of the form, expanding on the original novel’s perspective by placing you in the shoes of not Fogg, but his loyal manservant Passepartout. Your task is not just to arrange Fogg’s journey (in which he takes a surprisingly passive role), but to see to his comfort and health, manage your finances, and along the way explore various side stories of which the consummate English gentleman remains blissfully unaware. 80 Days takes place in a steampunk-inflected world—Fogg and Passepartout travel by airship and mechanical carriage as well as train and steamer, and the game’s world features automatons who perform menial labor, and soldiers with robotic limbs. But it’s also a world undergoing political upheaval. Exploring the cities that he and Fogg visit, Passepartout falls in with Russian revolutionaries, freed slaves, secret Native American societies, and just in general, people who are wondering whether progress and modernity are all they’re cracked up to be, and what is lost when technology and capitalism remake the world.

The actual challenge posed by 80 Days is fairly easy—I came in well under the deadline on my first attempt, despite making several mistakes. So the real challenge is in figuring out the different ways that one can win Fogg’s wager—can you do it without visiting a bank or staying at a hotel? Can you arrive back in London in less than 70 days, or 60 or 50? How many different routes can you explore? And the real pleasure lies in pursuing the adventures that Passepartout can fall into as he travels the world, such as solving a murder on an airship, penetrating the secretive guild of artificers, romancing various characters, and even veering off into the plots of other Verne novels like 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea or Journey to the Center of the Earth. Which means that 80 Days has excellent replayability value, which is only enhanced by the game’s elegant, minimalistic interface. It’s a perfect midpoint between strategy game and storytelling game, and in both guises, it will take a long time to explore all the material that it offers.

Disco Elysium: The Final Cut (2019)

At first glance, Disco Elysium appears to be a familiar sort of game. You play debauched police detective Harry Du Bois, who wakes up in his hotel room, after what appears to have been an epic bender at the end of a long self-destructive streak, without any memory of who he is or even what world he lives in. Before long, the game establishes a classic hardboiled mystery—Harry is in Martinaise, the crime-ridden, crumbling neighborhood that surrounds the main port in the city of Revachol, to investigate the murder of a security contractor, killed in a gruesome lynching. The port is currently in the midst of a protracted strike, and the victim was part of a private security team brought in to suppress it. So is his death an eruption of rage by the union’s squad of enforcers? Or does it have something to do with Revachol’s bloody history, which encompasses a communist revolution, the brutal suppression of same, and a decades-old protectorate that has governed the city on behalf of moneyed interests from abroad? And what role does the femme fatale in the room next to Harry’s play in the story?

Despite its mystery premise, however, Disco Elysium is not an adventure game, full of puzzles to untangle—the game is, in fact, quite fastidious about pointing the player in the direction of the next step in Harry’s investigation, either through the suggestions of his partner, the sardonic, long-suffering Kim Kitsuragi, or through a list of tasks. Rather, it is an RPG, with Harry’s persona divided into more than twenty traits, some of them straightforward, such as Logic or Hand-Eye Coordination, and others more esoteric, such as Shivers (a preternatural sense of the city and its happenings) or Esprit de Corps (empathy towards other police officers, and an innate understanding of their culture). Completing tasks—whether case-related or otherwise—gains the player experience points, which can then be used to upgrade traits. Which in turn gives Harry greater insight into his surroundings, allowing him to unlock yet more tasks.

In other words, the goal of Disco Elysium isn’t to solve the case but to explore—explore Martinaise, learn about it and Revachol’s history, and try to puzzle out the reasons for Harry’s mental breakdown. The central conceit of the game is that each of Harry’s traits is a distinct voice in his head, carrying on a monologue (and at some points, a conversation) that stands in for the hardboiled mystery’s narrative voice, but here offering different perspectives on the character’s experiences, and on his growing (and increasingly horrified) understanding of himself. The result, as in the best sort of noir fiction, is bleakly poetic, a cross between an elegy for a city whose best days seem to be behind it (though the citizens Harry encounters often have vastly different interpretations of what those best days were) and the faintest flicker of hope for the future, the seemingly impossible idea that both Revachol and Harry can pull themselves back together.

Unlike most noir mysteries, however, Disco Elysium is also comfortable in the fantastical register, interjecting ideas from fantasy, science fiction, and horror into its worldbuilding. When Harry encounters a billionaire, the difference between their respective net worths is so pronounced that it breaks the laws of physics, bending light itself around the richer man. The central religious figure of the enlightened, expansionist age that Harry lives in is a woman whose lungs are said to have glowed, who may not even have been human. A side quest involving an abandoned church that is being turned into an EDM club reveals the existence of a two-millimeter hole in the universe, which will eventually expand and flood all of Revachol with nothingness. And when Harry finally learns the fundamental details of how the game’s world is constructed and how travel between continents is achieved, it’s a piece of fantastical worldbuilding so strange and carefully thought-through, it wouldn’t be out of place in the most detailed and satisfying fantasy novel.

Disco Elysium‘s developers ZA/UM are a collective founded in Estonia (though currently based in the UK), and one can sense echoes of that country’s history in the way they construct Revachol and the world around it. Harry’s investigation eventually comes to seem like an archeological dig, excavating the revolution beneath the counter-revolution, the monarchy beneath the revolution, the colonial expansion beneath the monarchy, and the double-edged sword of enlightenment beneath the colonial expansion. The case itself eventually turns on the realization that Revachol’s past is neither gone nor past, but is still lingering, waiting to erupt and wreak destruction decades after it was supposedly laid to rest. The breadth of the game’s world and its multiple perspectives aren’t always an unalloyed good—Harry is able to adopt any ideology, from strict communism, through free-market libertarianism, to racist nationalism, and the fact that the game takes a similarly skeptical approach to each one has a whiff of “both sides” to it (which is only exacerbated by the game’s eventual valorization of the Revachol police department; I know that a lot of people love this game but let’s be honest, it is totally copaganda). But this refusal to take a side is counteracted by the richness with which each of those sides is depicted—it is possible, for example, to become an expert in an invented offshoot of cod-Marxist philosophy that argues that a determined adherent will develop psychic powers that will allow them to accelerate crop yields through the sheer force of their ideological purity. I can’t remember the last game I played that featured such an incredible depth and complexity of storytelling, with the result that almost as soon as you finish a run of Disco Elysium, you find yourself wanting to dive back in again, hoping to explore a new, previously unknown corner, or simply to sink back into its startlingly real world.

Spiritfarer (2020)

Nominated for this year’s special Hugo for best video game (and along with Hades, one of two nominees whose developers were kind enough to provide evaluation codes for Hugo voters), Spiritfarer is a game that combines elements of crafting simulators, platformers, and visual novels, a combo that doesn’t entirely hang together, but nevertheless makes for an addictive gameplay experience. You play Stella, who has taken over from Charon as ferrywoman for the dead. Instead of the river Styx, Stella sails her ship between the islands of an archipelago, picking up spirits, who then have to be made ready to pass over by indulging their wishes—their favorite food, a comfortable house, and time to talk about the twists and turns of their lives. In order to provide these amenities, Stella scrambles to gather resources and build crafting stations—everything from a kitchen to a cow pen to a smithy—and expand the abilities of her ship. The obols with which the passengers pay for the journey can be used to enhance her running and jumping abilities, increasing access to ever-more-esoteric resources. Along the way, we learn about Stella’s own life as a palliative care nurse, and about the reason that she’s suddenly taken over the Spiritfarer job.

Laying it all out like that makes it clear how contrived Spiritfarer‘s premise and gameplay are, and there are often times when the game’s disparate components feel like they’re at war with each other. Stella’s sad backstory can feel like a distraction from the more game-ish aspects, and it can be annoying when a particular task requires a great deal of leaping around to get the resources for (especially if you’re like me and are significantly worse at platforming than crafting). Perhaps most crucially, because both the game and each individual spirit have set storylines, Spiritfarer is a lot more “on rails” than its initial gameplay might suggest. The world of the archipelago and distribution of resources within it are not procedurally generated, which cuts into replayability. (Developers Thunder Lotus Games seem to be aware of this pitfall, because they’ve released a series of free updates, including new spirits, islands, and crafting abilities, throughout 2021.)

At its best, however, Spiritfarer is all-consuming, the lure of just-one-more-task keeping me at it for hours on end. The game piles increasingly nonsensical tasks and lists on Stella’s shoulders, like collecting all of the fish that can found in the archipelago’s ocean, or tracking down photographs from significant moments in the life of one of her passengers. So that at any time there are always at least a dozen things to be done, each of which will provide you with a little dopamine hit when you accomplish it (though here, again, the structured nature of the game works against it; a lot of abilities and resources only become available late in the story, when there isn’t that much to do, creating a long and sometimes quite annoying tail). And maybe that’s part of the point Spiritfarer is making. Stella is so obsessed with taking care of her passengers, catering to their every whim and expanding her boat and its facilities along the way, that she forgets—or perhaps willfully ignores—her own reasons for lingering in the afterlife. If that’s the case, then the game undermines itself—it’s much more fun to waste hours collecting items and zipping back and forth between islands than it is to pause and reflect on your life.

Afterparty (2019)

The second afterlife-themed game I played this year (third if you include the hour I spent trying to make Hades work for me) is Night School Studio’s follow-up to the magnificent, eerie, time-travel-meets-ghost-story conversation simulator Oxenfree (2016). This new game holds on to some of the horror tropes of the earlier one, but in a more comedic register, which isn’t nearly as effective. The protagonists are Milo and Lola, two lifelong best friends and recent college graduates who discover that they have died and gone to hell. Convinced that there has been a mistake, the duo embark on a rambling journey across hell’s islands (yet another archipelago here) with the ultimate goal of challenging Satan himself to a drinking game, in the hopes of winning a ticket back to the land of the living. Along the way they encounter various demons (most of whom are working stiffs just looking to unwind after a long day’s hard torturing), involve themselves in the dramas of several lost souls, work through some of their own relationship issues, and imbibe a truly epic amount of demonic alcohol.

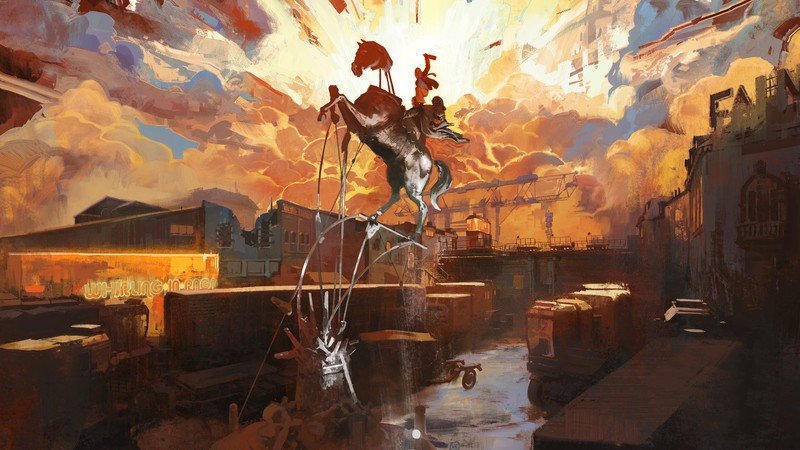

Afterparty‘s main claim to fame is how it envisions hell, as a dilapidated, seedy urban landscape dotted with neon signs and puddles of mysterious bodily fluids. Not the most original concept, to be sure, but it’s well-realized here, with painterly animation that stresses the strangeness of the landscape against the much-smaller character design, and a soundtrack that combines creepy environmental noises and the annoying club music that assaults Milo and Lola whenever they venture into yet another drinking hole. Unfortunately, that’s about the extent of the praise I can offer for this game, which in terms of plot and character development somehow manages to be both too short and too slow, its long stretches of tedious back-and-forthing between islands in pursuit of yet another intermediate task failing to lay the groundwork for its emotional breakthroughs.

Oxenfree‘s central mechanic was its conversation system, in which the player’s choices affected how the relationships between the five teens at its center would change and develop over the course of a single, haunted night. Afterparty tries to one-up that system by adding alcohol to it. Depending on which drink they’ve selected, Milo and Lola’s conversation options take on different personalities, from flirty to bold to talking like a pirate. But it quickly becomes clear that none of this actually matters. There’s very little you can do with conversation choices to change either the plot or the progression of the protagonists’ feelings for each other. So between the rather thin storyline (which often hinges on playing drinking games like beer pong or glass stacking—i.e. the sort of thing that’s only amusing if you’re buzzed yourself) and the static characterization, there doesn’t seem to be much here to play for.

Perhaps the biggest problem with Afterparty is that Milo and Lola themselves just aren’t that interesting. Their dysfunction seems fairly obvious from the game’s earliest scenes—Lola is cynical and misanthropic; Milo is insecure and clingy; together they’ve forged a codependent bond that keeps them from forming new relationships or breaking out of their comfort zone, and they’ve squandered the opportunity for reinvention that college afforded them. But the game never goes much deeper into it than that first impression, and there’s no real moment of catharsis between the two friends. Around the edges of their story, the game tries to develop the various denizens of hell—the psychopomp/cab driver Sam who ferries them around and gives them the lowdown on the underworld’s functioning; the various princes of the realm; and even Satan himself, who turns out to be a pretty chill guy (elevated by a great voice performance by Dave Fennoy, the highlight in a game whose voice acting is generally top-notch), with some deep-seated issues that are starting to come to the surface. But there isn’t enough depth to any of these depictions, and we don’t spend enough time with most of these characters to care about their problems. Night School have recently announced a follow-up to Oxenfree, forthcoming next year. Here’s hoping they can get back to what made that game affecting and engrossing, and that Afterpary was merely an unfortunate detour.