Telling the Truth about Poverty

There’s been this weird shift in LGM comments, especially since the elections last month in Virginia, that telling the truth about society is bad because it alienates voters. There’s even been a serious of insane comments from multiple people in multiple threads that I personify the problem with the left wing of the Democratic Party because I talk about the connections between parental choices around schools and racism. This seems pretty politically unrealistic to me. It’s also just morally insane. Not telling the truth about racism is a good thing now? How exactly does that work again?

In any case, not only is the case that talking about race bad politics highly questionable, but there’s also no way around it if we want to create structural change in this nation. As such, I want to point to this recent essay by former Stockton mayor Michael Tubbs about how we talk about poverty and how we need to talk about it:

We absolutely can implement bold policies on the local, state and federal levels that will dramatically change the trajectory of people’s lives, eliminate poverty and improve the nation’s productivity. But we can only achieve that kind of change if we disrupt and replace the current narrative on poverty based on racist, classist, sexist and xenophobic stereotypes. It’s a narrative that blames people for their struggles — labeling them as lazy, corrupt, unintelligent or worse — and deems them undeserving of our trust, our investment or even their own dignity.

This framing allows politicians to ignore and maintain blatantly unjust systems that keep people trapped in poverty — like jobs that pay unlivable wages or students at poor schools not having adequate, if any, access to resources like guidance counselors and extracurricular activities that affluent schools provide.

By viewing poor people as less than wealthier people — or even as disposable — actions like treating their communities as America’s dumping ground for hazardous waste and pollution will continue, all while leaving them barren of health care infrastructure.

A narrative that blames people for not rising out of poverty also permits policymakers to look the other way as so many young people are denied access or priced out of continuing education, even when we know higher education is necessary (though not a silver bullet) for advancing in today’s economy. It’s a narrative that contributes to continual mass incarceration that breaks up families and strips talent and potential from Black and brown communities.

But what would happen if we were to replace this false and destructive narrative with an authentic one that centers the experiences of people who actually live in poverty? These are people like my mother, grandmother and aunt — my “three moms,” as I refer to them in my memoir “The Deeper the Roots”— who together raised me while my father served a sentence of 25 years to life due to a draconian “Three strikes, you’re out” law. A fundamental shift in how communities like the one I grew up in are talked about would recognize the strengths, assets and dignity of individuals and families. It would look squarely at how people are set up for failure through under-resourced schools, low pay with no benefits, over policing and much more, and it would therefore create space for new policies that would, as I call it, upset the setup.

The stakes for a new narrative, new politics and new policy around poverty couldn’t be higher. That’s why I launched that seemingly radical policy pilot in Stockton and why lawmakers from both parties in cities across the U.S. are now following suit.

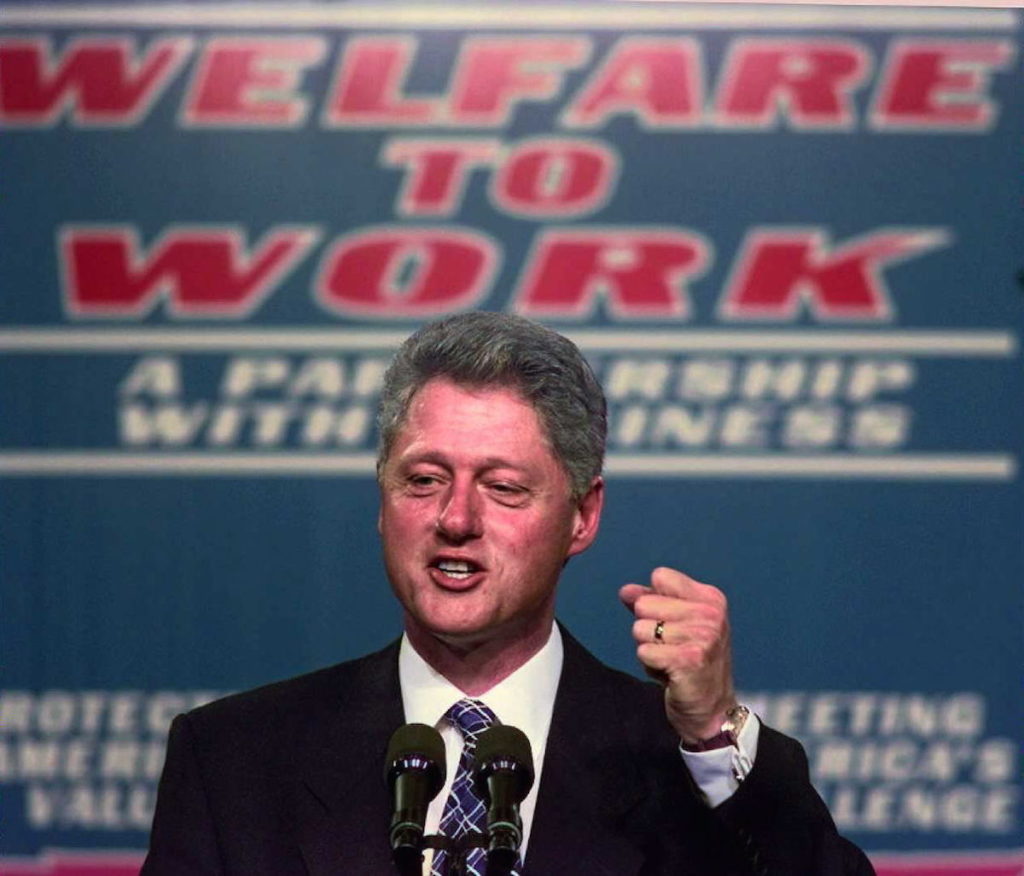

See, the biggest part of the reason we don’t really advance the poverty issue in this nation is that we use language that sees the poor as the problem and we have to fix them. See my old friend Bill Clinton destroying Aid to Families with Dependent Children as one great example. The most basic language in discussing poverty immediately goes to racial stereotypes (the Black welfare mother having as many kids as possible is just one example). Only by talking about how this framing is inherently racist can we move the conversation forward to a place where we can really get a handle of poverty. This is one of many similar issues in our country. If we aren’t going to talk honestly about racism and classism wherever they lay, no matter who doesn’t like it, then we are never going to get better as a nation. And that’s not acceptable.