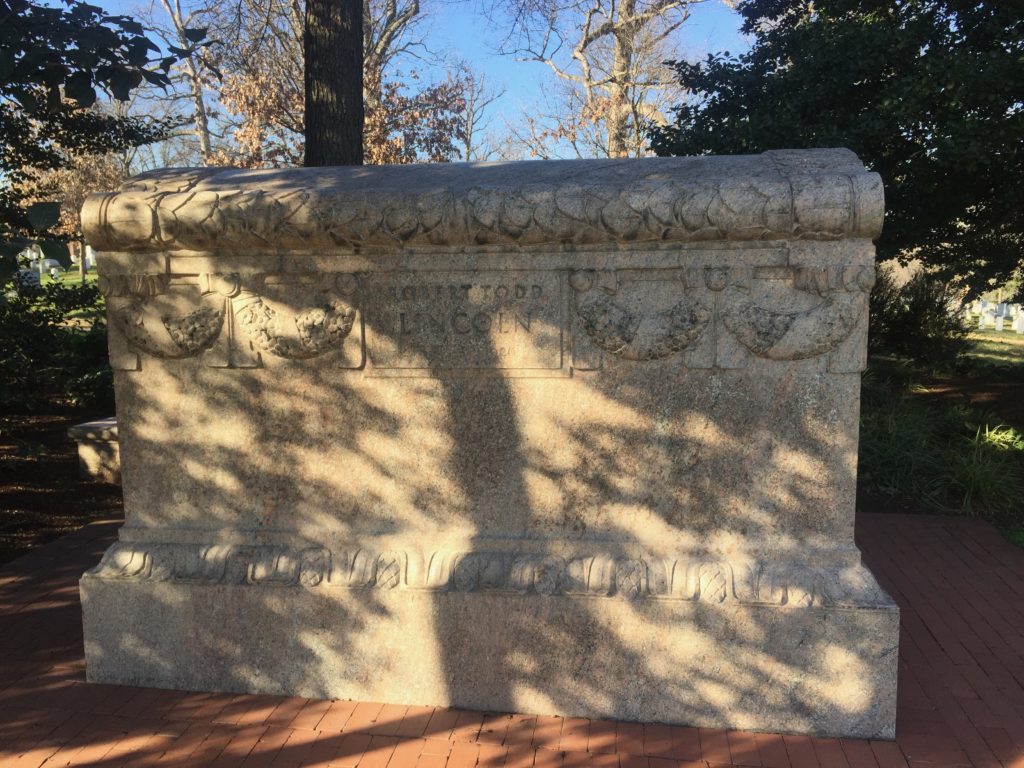

Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 975

This is the grave of Robert Todd Lincoln.

Born in 1843, Lincoln, as you all know, grew up the child of Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln. For his first 18 years, this was no great or unusual burden. After all, Abe was just a guy, a lawyer and low-level politician who no one knew. The fact that he served a term in Congress was no great shakes in the north since that was really common. Robert grew up in Springfield, Illinois and had high ambitions for himself. In 1859, he took the entrance exam to get into Harvard…..but he failed 15 out of the 16 subjects. Still wanting to go there (or at least his parents wanted him to), he enrolled at Phillips Exeter to get him the necessary elite social connections academic training to get accepted. It worked. He was accepted in 1860 and graduated in 1864.

During Lincoln’s time at Harvard, his father was…..occupied. In fact, it was strange for the young man to be at this elite institution not fighting the war when his father was running the war, even as lots of rich kids bought themselves out of service. And don’t think plenty people didn’t notice this. Now, Robert Lincoln was no great student. He was not an exciting guy at all. He had a mediocre mind and wasn’t very interesting. To be fair, this was no different than much of the young emerging Gilded Age elite. But he was a limited sort. But that wasn’t stopping anyone in the Gilded Age. He decided to go to Harvard Law after he graduated and did so until January 1865 when he finally managed to finagle his way into the Army. But he was the president’s son after all, so he wasn’t going to be thrown into the lines. After all, Mary Todd Lincoln did everything she could to keep her boy out of the war, against his own wishes. So Abe got Robert a job on Grant’s staff and didn’t do anything before he was mustered out soon after the war ended. He was almost at Ford’s Theater when his father was shot but chose not to go. He wasn’t real close with his dad anyway.

After Abe’s assassination, the family moved to Chicago. Lincoln took law classes at what is today Northwestern University and was admitted to the bar in 1867. He then became a Gilded Age railroad lawyer hack. He lived in Chicago and was in local politics for awhile. But his name always meant he could tap into bigger things, not because he was particularly competent, but because his name alone could smooth over the tremendously fractious Republican Party. At least he knew his own limitations. Hayes wanted to name him Assistant Secretary of State, despite the fact that he had no foreign policy experience at all. He decided against this. But then when Garfield offered him Secretary of War, he jumped on that. He stayed through the Arthur administration. Lincoln was named to the position both because of his name but also as a sop to the Grant third termers, of which Lincoln was one. Interestingly, Lincoln was not a big Grant supporter during his presidency, but his anger over the repression of Black voting in the aftermath of the Compromise of 1877 made him want a strong figure on that point, which Grant was for all his other failings. As Secretary of War, he was….whatever. A non-entity primarily, someone who did the basic work of inspecting forts and the like, but he was a minor member of the Cabinet, particularly compared to someone like James Blaine, who was Secretary of State. To be honest, there wasn’t that much for a Secretary of War to do in the Gilded Age, so it would have been hard for him to really shine unless he had higher ambitions, which he did not.

During the first Cleveland administration, Lincoln went back to Chicago and mostly involved in charity operations and his law practice. Then Harrison sent him to London as ambassador. He was whatever at the job. U.S.-English relations were generally pretty chill at this time and he didn’t do much of note there. He was a big name, everyone knew that, and that’s why he was there.

Probably the most interesting about Robert Lincoln is how close he was to all three of the assassinations of Republican presidents during his life. Of course, he could easily have been at Ford’s Theater in 1865. He saw the Garfield assassination as he was with the president. And then he was just outside the building where William McKinley was killed in 1901. He developed a fatalistic sense of humor over this and I mean, what else are you going to do? Adding to this is that Edgar Booth, brother of John Wilkes Booth, probably saved Robert’s life on a train platform in 1863 or 1864 when he was nearly squeezed out of a crowded rail car and onto the tracks before Booth grabbed him and threw him onto the platform. Good times all around.

After all of this, Lincoln decided to work with a lovely man named George Pullman. He became general counsel for the Pullman Sleeping Car Company. In truth, he was Pullman’s right hand man. Of course, Pullman today is primarily known for one thing–the 1894 strike where he was so intransigent that he angered other capitalists but also got the Cleveland administration to use the military to crush the strike. Lincoln by all accounts was completely supportive of this. In fact, he was so close to Pullman that after the old bastard died in 1897, Lincoln became president of the company and changed little in its practices. Lincoln got very rich as Pullman president. It’s always extremely dubious to say that the parent would have the same politics of the child, we know this is often not the case. But it’s also worth noting that lots of abolitionists were on the front lines calling for the military to crush strikes as early as the 1870s and given that Abraham Lincoln was ultimately a moderate Republican, it’s entirely possible he would have seen things the same way his son did. In any case, Robert Lincoln built a gigantic mansion in Vermont that stayed in the family until the 1970s.

Lincoln lived long enough to appear at the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in 1922. He was pretty old though. He did in 1926, at the age of 82.

Robert Lincoln in buried on the confiscated lands of the traitor Lee, Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia.

If you would like this series to visit other Secretaries of War in the Gilded Age (and why wouldn’t you!), you can donate to cover the required expenses here. William Crowninshield Endicott is in Salem, Massachusetts and Redfield Proctor is in Proctor, Vermont. Previous posts in this series are archived here.