But Maddie and Connor Just Deserve the Best Schools

I’ve been chewing over this long profile of what happens when you push white liberals to participate in desegregation efforts, in this case in Minneapolis. Oh, it’s typical. A whole lot of whining about how “I’m not racist, I voted for Biden!” and “My children just deserve the best so nothing I do to make that happen can possibly be racist because that’s what those bad people do” and “The best schools inherently mean that my child can take all the AP classes even though because I am an active parent my child will be fine no matter where they attend school.” It’s all pretty depressing, pretty typical, and given the tenor of the white liberal racism that dominates the comment threads both in this Times article and here at LGM on this topic, a pandemic that continues to get in the way of this nation doing anything to fight for equality.

A few choice cuts:

When Mauri Friestleben learned that Minneapolis was rolling out a new school integration plan — and that the school she led, a predominantly Black, low-income high school, would soon include white students from some of the wealthiest neighborhoods in town — she looked around and proudly considered all that her school had to offer.

The hallways at North Community High are a tapestry of blue and white, the school colors, and the mascot, a polar bear, seems to roar around every corner. The curriculum had been updated to expand access to advanced placement courses: U.S. history, physics, art and design. The school had a new athletic field, and on the first floor, a radio studio.

But in some phone conversations with potential new families, Ms. Friestleben, the principal, sensed deep skepticism.

Parents peppered her with questions. Exactly how many A.P. courses did her school offer? Was Spanish the only language option? Would their children be safe walking from the bus? Some even wondered how she had gotten their number and asked her not to call again.

Ah yes, the critical questions.

“Everyone wants equity as long as it doesn’t inconvenience them,” said Eric Moore, senior officer for accountability, research and equity for Minneapolis Public Schools, where about a third of students — some 10,000 children of different races — were assigned to new schools this year.

The changes included redrawing school zones, including for North. “This plan is saying, everyone is going to be equally inconvenienced because we need to collectively address the underachievement of our students of color,” Mr. Moore added.

“Look, I have a Black Lives Matter sign outside my $800,000 home in a 90% white neighborhood. That’s the kind of equality I can get behind! But asking my children to attend school with those kids? C’mon….will they be safe? White lives matter too!”

But decades after Brown v. Board of Education, the dream of integration has remained just that — a dream.

Today, two in five Black and Latino students in the United States attend schools where more than 90 percent of students are children of color, while one in five white students goes to a school where more than 90 percent of students look like them, according to the Century Foundation, a progressive think tank.

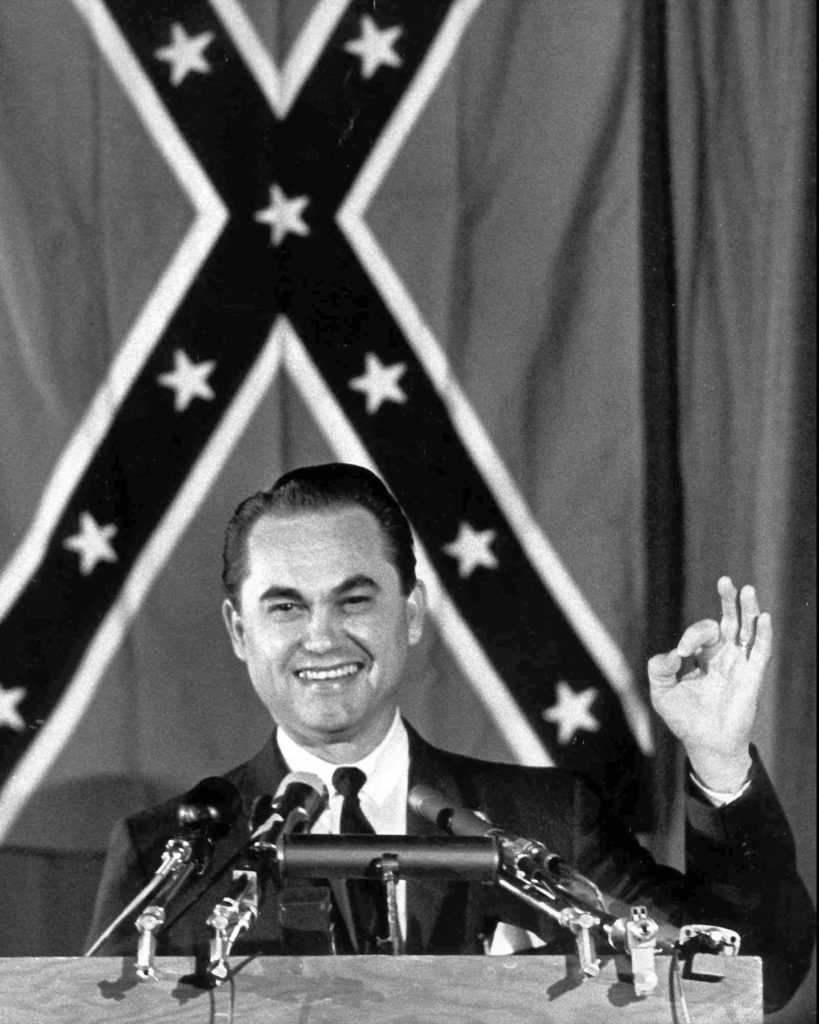

There’s not much difference between George Wallace and white parents who resist meaningful integration of their own schools. In fact, there’s no real difference at all.

If there is anywhere white families might embrace an integration plan, a likely candidate would be Minneapolis, which became the epicenter of the nation’s reckoning with racism after George Floyd’s murder last year. The city is 60 percent white and a bastion of liberalism, with a voting population that supported President Biden by 80 percentage points or more in some areas. In majority white neighborhoods, where homes can sell for $500,000 to $1 million, lawn signs proclaim “Black Lives Matter” and “All Are Welcome Here.”

But an up close look at one school, North High, and the cross section of families who traverse the new attendance zone, shows the complicated realities of school integration, even in a city with the political willpower to make it happen.

Your Black Lives Matter sign won’t get you into Heaven anymore.

Heather Wulfsberg, who is white, had intended to send her daughter, Isabella, 14, to Southwest High, a racially diverse but majority white public school that is a 10-minute bus ride from their home.

The school offers an international baccalaureate program, as well as Japanese, which Isabella studied in middle school. Isabella’s older brother, 18, is a senior there, and Ms. Wulfsberg envisioned her children attending together, her son helping Isabella navigate freshman year.

So Ms. Wulfsberg appealed the reassignment to North, citing her son’s attendance at Southwest, and her daughter’s interest in Japanese. (North offers one language, Spanish.)

She was also concerned about transportation. There was no direct bus, and Isabella’s commute could take up to 55 minutes. She would also have to walk from the bus stop to school through an area where frequent gun shots are a problem.

But Ms. Wulfsberg, who described herself as a lifelong Democrat, felt there was little room to explore her concerns without being misinterpreted or offending other families. Conversations on a Facebook page for parents turned tense.

One comment, in particular, stuck with her.

“They were like, ‘Your cover is, you want academics for your kids, and underneath this all, you really are racist,’” she recalled. “It’s a very scary feeling to do a self-examination of yourself and think, ‘Am I?’”

Yes. Yes you are a racist.

She paused, reflecting. “But I don’t believe I am. I really don’t.”

The family decided to send Isabella to a suburban school with top academic ratings. Students are about 80 percent white and about 4 percent economically disadvantaged.

I got nothing more to say.