This Day in Labor History: November 22, 1919

On November 22, 1919, a white supremacist terrorist organization called the Self-Preservation and Loyalty League murdered four union leaders organizing both white and Black workers at a sawmill in Bogalusa, Louisiana. Part of the interconnected white supremacist and anti-radical violence wave of terrorism during the Red Scare, the Bogalusa killings should be one of the most notorious labor incidents in American history, but remain largely unknown today. This is also a remarkable case of biracial labor cooperation, even if murderous violence would end it.

The Great Southern Lumber Company was part of the larger Goodyear empire. As with many small operations throughout the extractive economy, it was connected to one of the monopolies dominating the American economy in these years. Founded on the Louisiana-Mississippi border in 1902. The company went all-in with company unionism nearly from the beginning, bringing the YMCA in to provide educational programming, while the company built schools and other institutions. The idea was to keep out unions and the company leaders were extremely condescending toward workers in doing so. What was unique though is that the company also built a YMCA for its Black workers. The baseball diamonds in the town were kept in such good shape that the St. Louis Browns used them for spring training. But company domination over workers still rankled. The company ruled with an iron fist, all the way down to naming the police force. It had a huge private army to bust unions. This was also a somewhat unique work force in that while whites did hold the skilled positions, there wasn’t really that many of those in the timber industry and most of the grunt labor was not segregated. So white and Black workers labored together, doing the same jobs. Also, because these were nearly all-male spaces, the lumber camp did not violate the taboo of Black men being in touch with white women, making whites feel less threatened.

The American Federation of Labor had a lot of limitations in terms in organizing the working class, but when its unions wanted to work together, there was potential for progress. In what historians have argued is the most impressive display to build a biracial unionism in the early twentieth South, the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners worked with the International Union of Timber Workers to attempt to organize all workers in Bogalusa, beginning shortly after the conclusion of World War I. This came out of white workers in the town worried about the use of Black workers as strikebreakers and had the foresight to try and build unions with them instead of seeing them as the enemy. It’s not as if racial paradise was created as this developed. Black workers were organized into separate locals, they held separate Labor Day picnics, etc. So look, it was going to be limited in a Jim Crow context. But that doesn’t mean it wasn’t real. Getting to know each other meant learning about each other’s lives. Black and white workers started meeting together in private spaces, including each other’s homes. Part of what united them was a shared sense of outraged masculinity, as former independent farmers were not part of a proletarianized workforce and they did not like existing in a state of dependency.

There was a small but real tradition of unions in southern timber. The Knights of Labor had made significant inroads along the Gulf Coast in the 1880s, while Black and white workers fought together to try and unionize the timber industry along the Texas-Louisiana border between 1911 and 1913 through the Industrial Workers of the World, though massive violence led by the Pinkertons prevented them from succeeding. Meanwhile, unprecedented government intervention in the Northwest’s timber industry during World War I in order to stop the IWW and get the timber out created better labor conditions throughout timber elsewhere. Moreover, the Great Migration threatened companies such as Great Southern that used Black labor to try and undermine unionization efforts. When Great Southern reduced wages at the beginning of 1919, in the midst of an inflation bubble, workers were furious and joined the union in large numbers.

Lem Williams was the head of the union campaign, an Alabama-born white who had lived in Bogalusa since 1907. He wrote Samuel Gompers, “The success of the entire labor movement of the South depends on this fight.” The company went all in on race baiting to bust the union, sending out flyers to workers saying that unions meant social equality and a threat to all white women. The company was maybe OK with an all-white union but would not accept any Black workers in unions. The white unionists though really did show solidarity with the Black workers. When Black unionists were forced out of town, the whites held a march through the main street of town in support of them, defying the company. By September 23, 95 percent of the workforce had signed up in the union. So the company shut down the mills. It also created the Self-Preservation and Loyalty League to serve as a vigilante force of the “respectable” classes. This was intentionally a combination of the Ku Klux Klan and the anti-labor forces committing violence around the nation in these years. It claimed that the Bolsheviks (i.e. the AFL) had as a central tenet that any Black man could have sex with a white woman. Etc.

The head of the Black unionists was Sol Dacus, a 57 year old worker. He had grown up in Reconstruction Alabama and was a fighter for Black rights, influenced by those Reconstruction leaders of his youth. He started working in the timber industry at the age of 14. He started getting involved in the labor movement in the 1890s while working the docks in Mobile, where the Knights of Labor still had a strong presence. The SPLL mob decided to kill him. They marched to his house. He wasn’t home. So they killed his dog. Then they fired on his house. They almost killed his wife and kids but missed shooting them. Dacus came upon it and hid in trees, close enough he could hear the mob talk about whether they should burn the house down with his family inside. They decided not to but then ransacked the house. Dacus spent the night in a swamp.

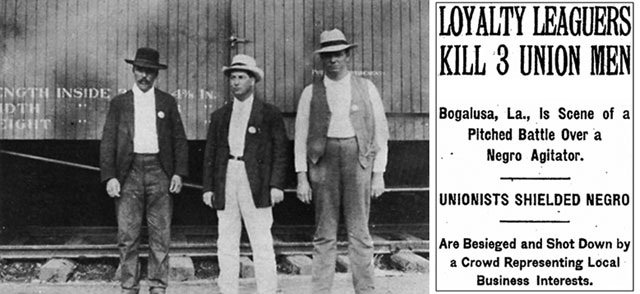

On the morning of November 22, 1919, Dacus walked down the street in Bogalusa with Stanley O’Rourke and J.P. Bouchillon, both white, next to him. This open defiance of the lynching attempt was an act of incredible bravery. The whites announced to all who could hear they would protect Dacus and then they walked into the offices of town’s Central Trades and Labor Council, which was in Williams’ auto repair garage in order to send a message of the Department of Justice in Washington about the lynching attempt. This infuriated the town’s whites. The Great Southern used its whistle to call out the mob to take care of these unionists once and for all. There were 7 union men inside the garage with about 150 white racist anti-unionists shooting outside. Within minutes, Williams, Bouchillon, O’Rourke, and a carpenter named Thomas Gaines were shot and killed. But Dacus got away, sneaking out the back.

In the aftermath, the Louisiana state AFL demanded justice for the workers, regardless of race. The formed the Union Liberty League as a coalition against the murder of unionists. They appealed to Washington, but the loathsome Attorney General, A. Mitchell Palmer, refused to do anything. In fact, 13 of the mob were arrested, but of course none were convicted, though neither were any of the survivors of the shootings that the company wanted charged. Dacus sued Great Southern for $102,000 in a civil suit, with the backing of organized labor. By this time, he had fled to New Orleans with his family and was working in a grain elevator before moving to Gulfport, in part to raise money for his own defense. In 1925, the all-white jury found for the company and Dacus got nothing. The wife of Williams actually took her case all the way to the Supreme Court, which also ruled in favor of the company, with no concern that had the legal mob “arrested” Dacus, they would have lynched him.

The killing of the union leaders ended the union drive in Bogalusa, but other mills in the area would continue fighting for unions for another year or so.

This post borrowed from Stephen H. Norwood, “Bogalusa Burning: The War Against Biracial Unionism in the Deep South, 1919,” published in the the Journal of Southern History in 1997.

This is the 417th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.