This Day in Labor History: November 15, 1975

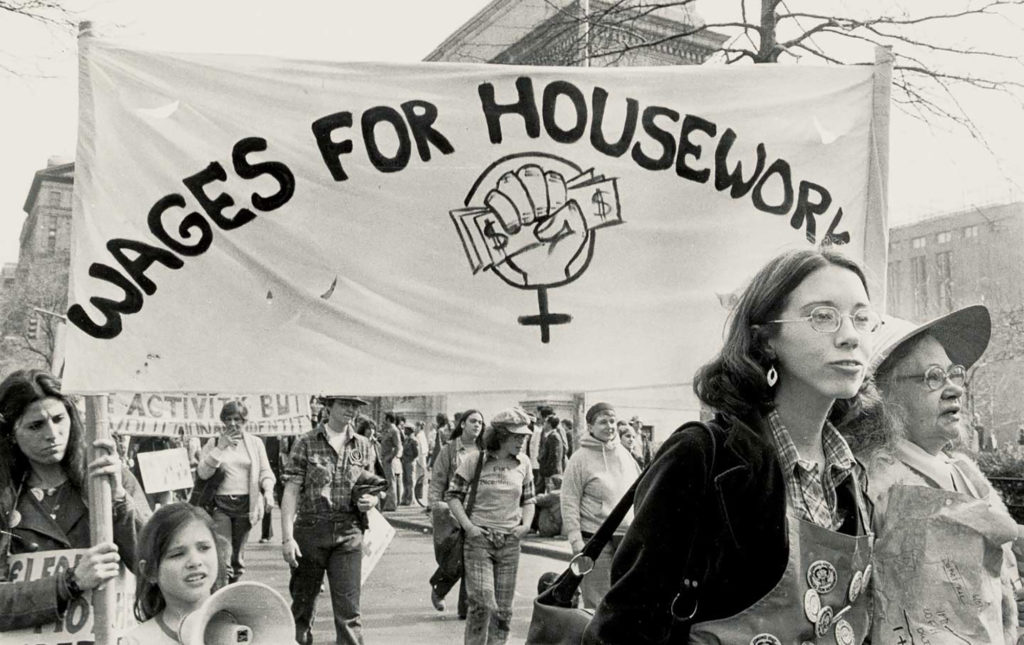

On November 15, 1975, Wages for Housework opened its storefront on 5th Avenue in Brooklyn. This date allows us to explore this fascinating intersection between the feminist movement and ideas of work, with many lessons for the present. While the idea of being paid for housework had a strongly international dimension, we will focus on the American side of this story for today.

As feminism rose as political force in the late 60s and early 70s, there were lots of debates on what its political objectives should be. Not surprisingly, the winner in these debates were upper-middle class white professionals, who prioritized rights over justice, preferring to fight for the Equal Rights Amendment and right to an abortion than the welfare rights and other economic justice issues prioritized by many Black feminists.

One of the smaller but still significant economic justice demands coming out of early feminism was the idea of women getting paid for housework. Reproductive labor has never received the respect it deserves in the labor world, from unionists or historians or anyone else. Because it isn’t seen as wage labor, it doesn’t fit into the Marxist framework behind our class conversations. But no labor under a capitalist or socialist system happens without the reproductive labor to keep society stable. So what if we put an economic value on it and paid the people doing this labor that is more necessary than any other form of labor?

Wages for Housework was a movement in the U.S. led by Silvia Federici, an Italian activist who moved in the U.S. in the late 1960s for graduate school and who co-founded the International Feminist Collective. She then became the leader of the U.S. side of the Wages for Housework movement, an international set of activists focusing on liberating women from housework in part by paying them for that labor. They based their ideas on Mariarosa Dalla Costa and Selma James’s 1971’s essay “The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community,” which argued that labor within the home was the same as labor outside the home and that women couldn’t be freed from patriarchal oppression without this fact being recognized and revolutionized.

Wages for Housework touched on many key themes of feminism, including the unspoken second job for women–working outside the home for wages and inside the home without wages–which had plagued women ever since they entered the industrial workforce. Correctly arguing that reproductive labor was the foundation of industrial work, it demanded proper compensation within this capitalist economy and lambasted the left for not taking these questions seriously. It was a lesbian-centered movement that argued that lesbians actually deserved even more compensation for their work because of the economic disadvantages that all women faced in the workforce, plus the psychic burden of homosexuality within a hetero-centric world. In fact, when Wages Due Lesbians, one sector of the larger WFH movement, created its own manifesto in 1975, they called it “Fucking is Work,” an intentionally provocative title that demonstrated the challenge these women gave to ideas of both mainstream feminism and the entire society’s conceptualization of work and gender. It called for direct action by women at the workplace and for women of color to start their own groups within the larger movement to focus on the issues that most mattered to them. It was strongly pro-sex work at a time when much of feminism was demonizing sex workers and seeking to ban pornography. It never had too many adherents, but it opened a store in New York on November 15, 1975 and had a few chapters across the country. The store itself didn’t stay open that long, but it does serve as a useful date for this series so I can write about this group and their ideas. In fact, WFH was basically dead by 1977, though its founders remained influential thinkers in the world of women’s work and women’s liberation for decades and many, including Federici, remain active today.

WFH didn’t get too mired in policy details of precisely how much women should be paid or how this work–that really wasn’t the job of the women behind it. They were trying to make a point. But they did see Aid to Families with Dependent Children and other parts of the nation’s limited welfare state as part of the answer, thus making them among the only influential groups of white women within feminism to ally with Black feminists over their priorities. Moreover, no mainstream voices in labor and very few in feminism have ever articulated a meaningful response to Federici’s challenges or how to classify unpaid reproductive labor at all. Behind this reluctance is not just an intractable problem of conceptualization or implementation. It’s that the labor movement has traditionally had a huge sexism problem it has never fully faced up to and that mainstream feminism has a huge class problem that it also refuses to take seriously. Federici and the Wages for Housework activists attempted to challenge both and if it didn’t get too far, the challenge remains there for us to pick up today.

This is the 416th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.