Racist Historical Markers

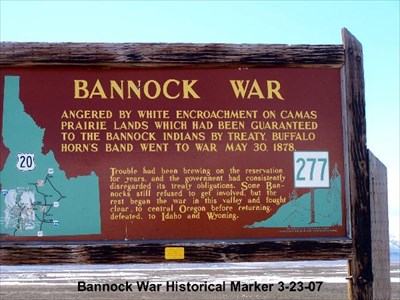

Historical markers not only vary by state but by region. In New England, they basically don’t exist. We don’t have to bother with such things, we are history (eyeroll, but that’s the attitude). In the South, they tend to be everywhere, but in tiny print and often on trivial things (east of Georgetown, Texas there’s one on the history of the first grist mill in the region, for example). In the West, they tend to be more state sponsored and more like roadside monuments, often quite large. They were often put up in the 40s and 50s as part of the modernization projects of the mid-20th century. That means they reflect the popular historical understanding of the time period, i.e., the period when Arthur Schlesinger didn’t even mention Indian Removal in The Age of Jackson because there simply wasn’t a place for Native people in the vision of America that New Dealers had. So the historical markers are often super racist toward the tribes. That needs to change. In Idaho, of all places, that is leading to a campaign to change them.

In September of 1824, a Scottish schoolteacher turned fur trapper made his way to a mountain summit overlooking the awe-inspiring Sawtooth Valley near present-day Sun Valley, Idaho. Historical Marker 302 on Highway 75 at Galena Summit now commemorates the moment when Alexander Ross and his entourage first stood at the spot above the headwaters of the Salmon River. The sign proclaims that Ross “discovered” the summit before spending another month traveling “mostly through unexplored land.”

The notion that Ross “discovered” any place that had not already been well traveled by Native Americans strikes Idaho State Historic Preservation Office Deputy Tricia Canaday as absurd. “Of course, Indigenous groups had been traversing that route for millennia,” she said. Canaday has taken on the monumental task of working with Idaho’s five tribes to revise many of the 290 signs in the states’ historical marker system, and possibly add new signs.

The initiative’s stated goal, Canaday said, is to rebalance Idaho’s roadside history with an Indigenous perspective and thereby create a more culturally sensitive and historically accurate picture of the past. Each state in the U.S. appears to have its own standards and protocols for reviewing highway marker language, she said, and her office is in charge of Idaho’s. As a result, Ross may soon be known for having “mapped” or “encountered” Galena Summit, rather than discovering it, Canaday said. That might seem like a small success, but it’s just one piece in a wider mosaic that could transform Idaho’s roadside history for generations to come.

Leading this effort alongside Canaday are tribal officials like Nolan Brown, an original territories researcher at the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes’ Language and Cultural Preservation Department at the Fort Hall Reservation. The revision of highway markers is now part of his job, which since 2017 has included the creation of new interpretive signs and exhibits around the state related to his community. “Our major purpose is to educate tribal members and the public and build awareness about the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes’ history and continued presence in all of our original territories,” Brown said.

Of course Idaho whites will probably engage in a decades-long backlash over such things…..